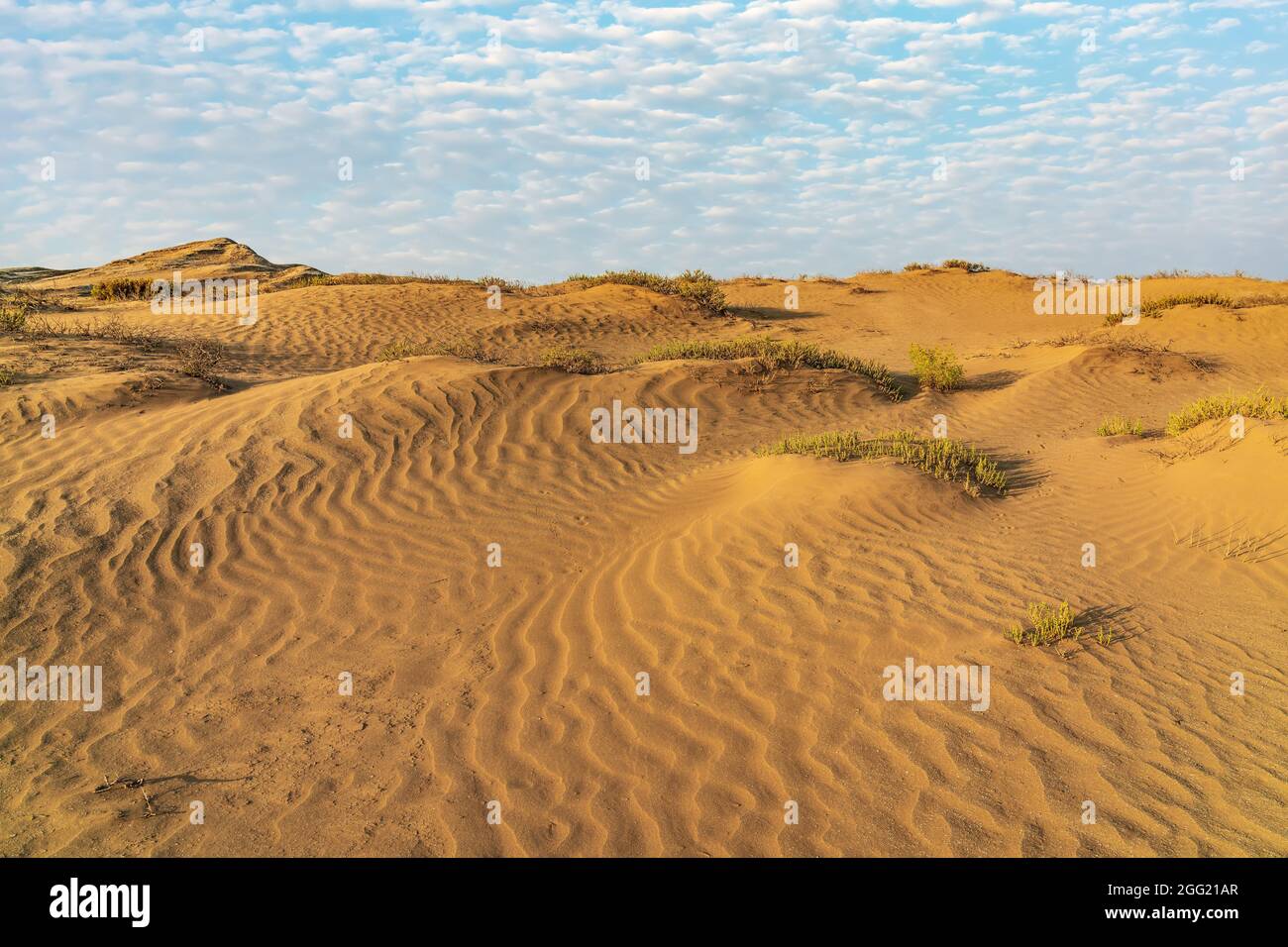

Imagine a landscape sculpted by wind and sun, a realm of seemingly endless sand and rock. It might appear desolate, but look closer. These arid environments, often called deserts, are teeming with life – incredible, resilient life. We’re talking about desert animals, creatures that have mastered the art of survival in some of the harshest conditions on Earth. For me, there’s something profoundly inspiring about witnessing how life finds a way, and nowhere is that more evident than in the world’s deserts.

This blog post is a deep dive into the fascinating strategies these animals employ to not just survive, but thrive in the face of extreme heat, scarce water, and limited food. We’ll explore how animals in the desert have evolved remarkable physiological adaptations – from incredibly efficient kidneys to ingenious methods of metabolic water production. But it’s not just about biology; behavior plays a huge role. Think nocturnal habits, clever burrowing techniques, and even cooperative cooling strategies.

We’ll journey across the globe, from the scorching Sahara to the arid landscapes of North America and Australia, discovering the unique desert animals that call each region home. You’ll meet iconic species like the camel, the fennec fox, and the sidewinder snake, and learn about their specialized diets and incredible abilities. Beyond the well-known, we’ll also uncover the resilience of smaller creatures – insects, arachnids, and rodents – that are equally vital to these fragile ecosystems.

But this isn’t just a celebration of adaptation. We’ll also confront the challenges facing these incredible animals, from the looming threat of climate change to the impact of habitat loss. Ultimately, understanding how these creatures survive offers valuable insights into conservation and the importance of protecting these unique and precious environments. So, let’s embark on this journey together and uncover the secrets of life in the desert animals‘ world.

Understanding Arid Landscapes

Deserts. The very word conjures images of endless sand dunes, scorching sun, and a seemingly desolate emptiness. But to call a desert “empty” is a profound misunderstanding. These landscapes, though challenging, are teeming with life – life that has adapted in extraordinary ways to not just survive, but thrive in conditions that would quickly overwhelm most other organisms. This section will delve into the fundamental characteristics of desert ecosystems, the hurdles faced by creatures inhabiting them, and the remarkable global distribution of these fascinating environments. It’s a journey into a world where resilience isn’t just a trait, it’s a necessity.

Defining Desert Ecosystems

What exactly is a desert? The common perception – a vast expanse of sand – is only a small part of the story. A desert is, fundamentally, defined not by its temperature, but by its aridity. Specifically, a desert receives less than 250 millimeters (10 inches) of precipitation per year. This low rainfall dictates the entire character of the ecosystem. However, this definition encompasses a surprising diversity of landscapes.

We often categorize deserts into several types: hot deserts like the Sahara and the Sonoran, characterized by high temperatures year-round; cold deserts like the Gobi and the Antarctic Polar Desert, where temperatures can plummet below freezing; semi-arid deserts like the Great Basin, which experience slightly more rainfall and support a greater variety of vegetation; and even coastal deserts like the Atacama, which are influenced by cold ocean currents and experience fog as a primary source of moisture.

The vast and iconic landscape of the Sahara Desert

The vegetation in a desert ecosystem is sparse and highly adapted. Plants often exhibit features like deep root systems to access groundwater, succulent tissues to store water, and reduced leaf surface area to minimize water loss. Cacti, succulents, and drought-resistant shrubs are common examples. The animal life, as we’ll explore in detail, is equally specialized. The interactions between these plants and animals, shaped by the scarcity of water and the harsh climate, create a unique and fragile ecological balance. It’s a system where every drop of water, every scrap of food, and every moment of shade is precious. The concept of a desert ecosystem isn’t about lack of life, but about life existing in a state of constant, ingenious adaptation.

Key Challenges for Desert Life: Water, Temperature, and Food

Life in the desert presents a trifecta of challenges: water scarcity, extreme temperatures, and limited food resources. These aren’t independent problems; they are intricately linked. The lack of water directly impacts the availability of food, as plant growth is severely restricted. The high temperatures exacerbate water loss, creating a vicious cycle. And the harsh conditions make it difficult for animals to find shelter and regulate their body temperature.

Water is, without a doubt, the most critical limiting factor. Desert animals have evolved a remarkable array of physiological and behavioral adaptations to conserve water. These range from highly efficient kidneys that produce concentrated urine to the ability to extract water from their food. But even with these adaptations, water remains a constant concern.

Temperature fluctuations are equally demanding. Daytime temperatures can soar to unbearable levels, while nighttime temperatures can drop dramatically. This extreme diurnal range poses a significant challenge to maintaining a stable internal body temperature. Animals must find ways to avoid overheating during the day and prevent hypothermia at night. Strategies include seeking shade, burrowing underground, and utilizing behavioral mechanisms like basking and huddling.

A kangaroo rat a master of water conservation foraging for seeds in the desert

Food resources are often scarce and unpredictable. Desert plants are often widely dispersed, and their growth is dependent on infrequent rainfall. This means that herbivores must travel long distances to find food, and carnivores must be opportunistic hunters. Many desert animals have adapted to survive on a limited diet, and some are capable of storing food for later use. The availability of food is often tied to seasonal changes and unpredictable events like flash floods, which can temporarily boost plant growth. The struggle for survival in the desert is a constant balancing act between finding enough water, regulating body temperature, and securing a reliable food source. It’s a testament to the power of natural selection that so many species have managed to overcome these obstacles.

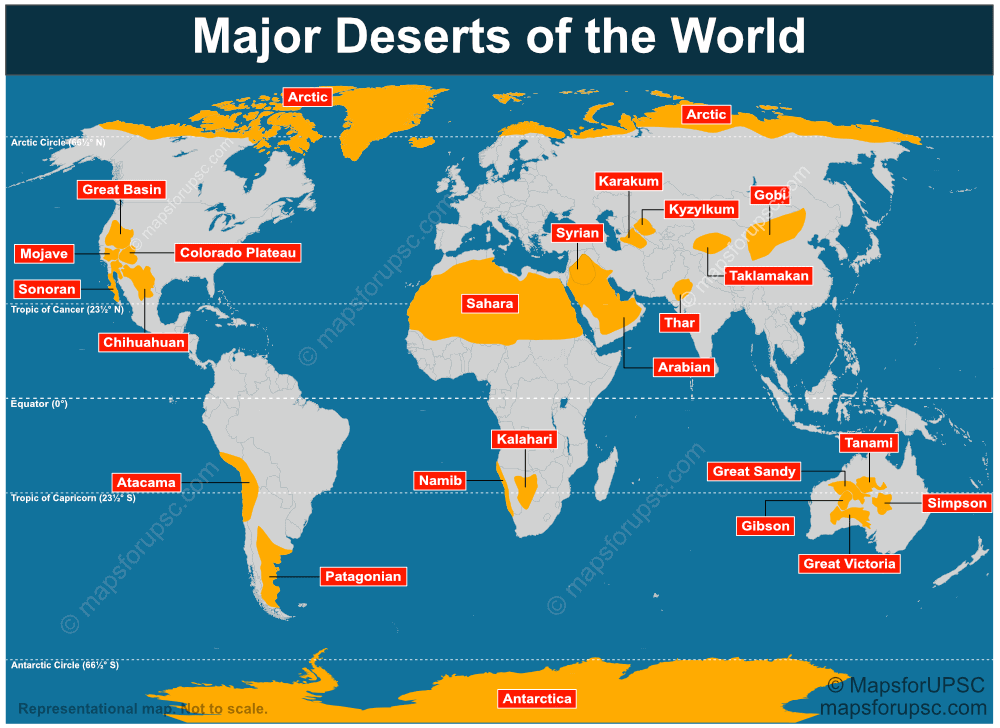

Global Distribution of Deserts

Deserts aren’t confined to a single region; they are found on every continent, covering approximately one-third of the Earth’s land surface. Their distribution is largely determined by global atmospheric circulation patterns.

The major deserts of the world are often located around 30 degrees latitude north and south of the equator. These areas are characterized by descending air, which suppresses rainfall. The Sahara Desert in North Africa is the largest hot desert in the world, stretching across eleven countries. The Arabian Desert, the Australian Outback, and the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts of North America are other prominent examples of hot deserts.

A world map illustrating the global distribution of major desert regions

Cold deserts, on the other hand, are often found at higher latitudes or in rain shadows – areas sheltered from rainfall by mountain ranges. The Gobi Desert in Asia, the Antarctic Polar Desert, and the Great Basin Desert in North America are examples of cold deserts. The Atacama Desert in South America is a unique case, a coastal desert created by the rain shadow of the Andes Mountains and the cold Humboldt Current.

The diversity of desert environments is reflected in the diversity of desert animals that inhabit them. Each desert has its own unique set of challenges and opportunities, and the animals that live there have evolved to exploit those specific conditions. From the camels of the Sahara to the kangaroo rats of North America and the thorny devils of Australia, the world’s deserts are home to a remarkable array of creatures, each a testament to the power of adaptation. Understanding the global distribution of deserts is crucial for appreciating the interconnectedness of Earth’s ecosystems and the importance of conserving these fragile environments. The study of animals in the desert provides invaluable insights into the limits of life and the remarkable capacity of organisms to adapt to even the most extreme conditions.

Physiological Adaptations for Water Conservation

The desert. A landscape often perceived as desolate, unforgiving, and utterly devoid of life. Yet, this perception couldn’t be further from the truth. The deserts teem with life, a testament to the incredible power of adaptation. And at the heart of survival in these arid environments lies one crucial element: water. Or, more accurately, the ability to conserve it. For desert animals, water isn’t just a necessity; it’s a precious commodity, a lifeline in a world where rainfall is scarce and evaporation rates are high. This section delves into the remarkable physiological adaptations these creatures have evolved to not only survive but thrive in the face of extreme water scarcity. It’s a story of ingenious biological engineering, honed over millennia by the relentless pressures of natural selection.

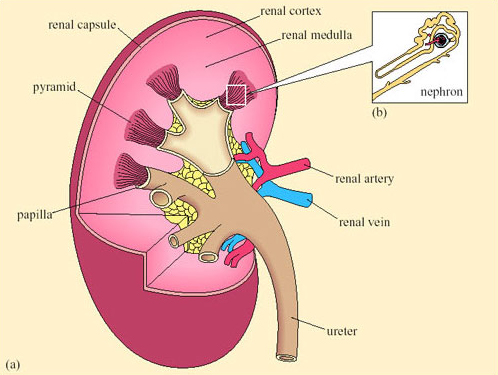

Efficient Kidneys and Concentrated Urine

Perhaps the most fundamental adaptation for water conservation revolves around the kidneys. These vital organs are responsible for filtering waste products from the blood, and in the process, regulating water balance. In mammals living in more temperate climates, kidneys produce relatively dilute urine, expelling excess water along with waste. However, desert animals have taken this process to an entirely new level of efficiency. Their kidneys are remarkably adept at reabsorbing water back into the bloodstream, resulting in the production of highly concentrated urine.

Diagram illustrating the highly efficient loop of Henle in the kidneys of a kangaroo rat enabling exceptional water reabsorption

Consider the kangaroo rat ( Dipodomys species), a quintessential desert animal of North America. These tiny rodents rarely, if ever, drink water directly. Instead, they obtain all the moisture they need from the seeds they consume. Their kidneys are so efficient that they can produce urine that is eight times more concentrated than human urine! This is achieved through an elongated “loop of Henle” – a structure within the kidney responsible for creating a concentration gradient that facilitates water reabsorption. The longer the loop of Henle, the greater the concentration gradient, and the more water can be salvaged. This isn’t limited to rodents; many desert reptiles also exhibit highly efficient kidney function, allowing them to excrete uric acid – a semi-solid waste product – rather than urea, minimizing water loss. The ability to produce such concentrated urine is a cornerstone of survival, allowing these animals to retain precious water even in the driest conditions. It’s a testament to the power of evolutionary pressure, shaping the very architecture of their internal organs.

Metabolic Water Production

But conserving water isn’t just about minimizing loss; it’s also about maximizing gain. And one surprising source of water for desert animals comes from within – through metabolic processes. Metabolism, the sum of all chemical reactions occurring within the body, generates water as a byproduct. This “metabolic water” isn’t a huge source, but in an environment where every drop counts, it can be a significant contribution to overall hydration.

The process is particularly important for animals that consume dry foods, like seeds or insects. When carbohydrates, fats, and proteins are broken down during digestion, water molecules are released. For example, the complete oxidation of glucose yields water as one of the products. Animals like the kangaroo rat, which rely heavily on seeds, are masters of metabolic water production. They’ve evolved metabolic pathways that maximize water yield from their food.

Illustration depicting how camels metabolize fat reserves to produce water carbon dioxide and energy

Camels, iconic desert animals, also utilize metabolic water production, but in a particularly fascinating way. They store fat in their humps, and when this fat is metabolized, it yields not only energy but also a substantial amount of water. This is a crucial adaptation for enduring long periods without access to drinking water. The chemical equation for fat metabolism highlights this: Fat + Oxygen → Carbon Dioxide + Water + Energy. While not a complete substitute for drinking water, metabolic water production provides a vital buffer against dehydration, extending the time these animals can survive in arid conditions.

Reduced Sweating and Panting Mechanisms

Evaporative cooling – sweating in mammals and panting in birds – is a highly effective way to regulate body temperature. However, it comes at a cost: water loss. Desert animals have evolved strategies to minimize evaporative cooling, reducing water expenditure while still maintaining a stable internal temperature.

Many desert mammals, like the fennec fox, have relatively small sweat glands compared to their counterparts in wetter climates. This reduces the amount of water lost through perspiration. However, simply reducing sweating isn’t always enough. Animals also need to cope with the intense heat without overheating.

A fennec fox showcasing its large ears which are highly vascularized and aid in heat dissipation

The fennec fox, with its famously large ears, provides a brilliant example of heat dissipation without significant water loss. These ears are highly vascularized – meaning they contain a dense network of blood vessels. As blood flows through the ears, heat is radiated into the surrounding air, cooling the animal down. The large surface area of the ears maximizes this heat exchange. Similarly, some desert birds employ a technique called gular fluttering – rapidly vibrating the throat pouch to promote evaporative cooling, but doing so with a smaller surface area than panting, minimizing water loss.

Reptiles, being ectothermic (cold-blooded), rely on behavioral strategies to regulate their body temperature, such as seeking shade or burrowing underground, rather than relying on evaporative cooling. This eliminates the need to expend water to maintain a stable internal temperature.

Water Storage Strategies: Fat Metabolism & Specialized Tissues

Beyond efficient conservation and metabolic production, some desert animals have developed remarkable strategies for storing water, or at least, storing resources that can be converted into water when needed. We’ve already touched upon the camel’s fat storage in its hump, which serves as both an energy reserve and a source of metabolic water. But the story doesn’t end there.

Certain desert rodents, like the kangaroo rat, exhibit specialized tissues capable of storing water. The tissues in their nasal passages are particularly adept at extracting moisture from inhaled air, preventing water loss during respiration. This is a subtle but significant adaptation, especially considering the dry air prevalent in desert environments.

Desert tortoises are another example of water storage prowess. They possess a remarkably large bladder that can store significant amounts of water, allowing them to survive for extended periods without access to a water source. They can absorb water through their cloaca (the common opening for the digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts) when standing in shallow puddles after rare rainfall events. This stored water can then be slowly released as needed, providing a crucial lifeline during droughts.

These water storage strategies, combined with the physiological adaptations discussed above, demonstrate the incredible ingenuity of desert animals in overcoming the challenges of life in extreme environments. They are a testament to the power of evolution, shaping these creatures into masters of survival in the harshest of landscapes. The study of these adaptations not only deepens our understanding of the natural world but also offers potential insights into developing innovative solutions for water conservation in a world facing increasing water scarcity.

Behavioral Adaptations for Surviving Heat

The desert. Just the word conjures images of scorching sun, endless sand, and a seemingly inhospitable environment. Yet, life thrives in these harsh landscapes. It doesn’t do so by brute force, but through an incredible array of behavioral adaptations – clever strategies honed over millennia to cope with the relentless heat. These aren’t just instinctive reactions; they’re complex, often fascinating, behaviors that allow desert animals to not just survive, but flourish. It’s a testament to the power of evolution, and a humbling reminder of life’s tenacity.

Nocturnal Activity Patterns

Perhaps the most recognizable behavioral adaptation to desert heat is nocturnality. While we humans tend to be diurnal creatures, active during the day, many desert animals have flipped the script. They become most active during the cooler hours of the night, escaping the brutal daytime temperatures. This isn’t simply a matter of preference; it’s a matter of physiological necessity.

Think about it: the sun beats down on the sand, raising the ambient temperature to levels that would quickly overwhelm most mammals. By waiting until the sun sets, these animals avoid the peak heat stress, reducing their need for water and energy expenditure. This shift in activity patterns impacts every aspect of their lives, from hunting and foraging to mating and social interactions.

The fennec fox, with its famously large ears (which also serve a thermoregulatory function, we’ll get to that later!), is a prime example. These adorable creatures spend the day sleeping in burrows, emerging only after sunset to hunt for insects, rodents, and reptiles. Similarly, many desert snakes, scorpions, and insects are primarily nocturnal, minimizing their exposure to the sun. Even larger animals, like some desert rodents, will adjust their foraging times to coincide with the cooler nighttime temperatures.

But nocturnality isn’t without its challenges. Navigating in the dark requires heightened senses. Many nocturnal desert animals have evolved exceptional eyesight, relying on the limited available light. Others, like scorpions, use vibrations to detect prey. The night also brings its own predators, so vigilance is crucial. It’s a delicate balance, a constant negotiation between the need to avoid heat and the need to avoid becoming someone else’s dinner.

Burrowing and Shelter Seeking

While nocturnality allows animals to avoid the heat, burrowing allows them to escape it. The ground, even in the desert, provides a relatively stable temperature compared to the fluctuating air temperature above. Digging burrows, or seeking shelter in existing crevices and caves, is a remarkably effective way to stay cool.

The temperature difference can be dramatic. Surface temperatures in the desert can soar to over 50°C (122°F), while the temperature just a few feet below the surface can remain a comfortable 20-30°C (68-86°F). This temperature gradient is exploited by a wide range of desert animals.

The entrance to a desert tortoise burrow providing crucial shelter from the heat

Desert tortoises, for instance, are masters of burrow construction. They dig extensive underground networks that provide refuge from both the heat and the cold. These burrows aren’t just simple holes in the ground; they’re carefully engineered systems with multiple chambers and ventilation shafts. They can even share burrows with other species, creating a sort of communal cooling center.

Smaller animals, like kangaroo rats, also rely heavily on burrows. They create complex tunnel systems that allow them to access cooler, more humid air. These burrows are so effective that kangaroo rats can often survive without ever drinking water, obtaining all the moisture they need from the seeds they eat and the metabolic water produced during digestion.

Even animals that don’t dig their own burrows will seek out natural shelters. Lizards will hide under rocks, in crevices, or in the shade of shrubs. Birds will nest in sheltered locations, such as canyons or caves. The key is to find a place where the direct rays of the sun are blocked, and where the air is cooler and more humid.

Estivation and Torpor

Sometimes, even burrowing and nocturnality aren’t enough. During periods of extreme heat or drought, some desert animals employ even more drastic measures: estivation and torpor. These are states of dormancy, similar to hibernation, but triggered by heat rather than cold.

Estivation is a prolonged period of inactivity, lasting weeks or even months. During estivation, an animal’s metabolic rate slows dramatically, reducing its energy and water requirements. It may burrow deep underground, seal itself in a cocoon, or simply find a sheltered spot and remain motionless.

An African lungfish estivating in a mud cocoon during a drought

A classic example of estivation is the African lungfish. When the waterholes they inhabit begin to dry up, lungfish burrow into the mud, creating a cocoon of mucus and clay. They can remain in this state for months, or even years, until the rains return.

Torpor, on the other hand, is a shorter-term state of dormancy, typically lasting hours or days. It’s a more flexible response to fluctuating environmental conditions. Animals in torpor experience a temporary reduction in body temperature, heart rate, and breathing rate. This allows them to conserve energy and water during periods of intense heat.

Many desert rodents, such as kangaroo rats, enter torpor on a daily basis. They’ll spend the hottest part of the day in a state of torpor, emerging only during the cooler evening hours to forage. This allows them to minimize their water loss and survive in an environment where water is scarce.

Social Behavior and Cooperative Cooling

While many desert animals are solitary creatures, some species have evolved social behaviors that help them cope with the heat. Cooperative cooling is a fascinating example of this.

Meerkats, those charismatic little mammals from the Kalahari Desert, are renowned for their social behavior. They live in groups, called mobs, and work together to survive. One of the ways they do this is through cooperative cooling.

Meerkats huddling together in the shade to regulate their body temperature

During the hottest part of the day, meerkats will huddle together in the shade, reducing their surface area exposed to the sun. They’ll also share burrows and take turns standing guard, alerting the group to potential predators. This cooperative behavior allows them to maintain a more stable body temperature and conserve energy.

Other social animals, such as desert bighorn sheep, will seek out shade together, reducing their individual heat stress. Even some desert birds will engage in communal roosting, huddling together for warmth during the cool nights and seeking shade together during the hot days.

The desert is a challenging environment, but it’s also a place of incredible adaptation and resilience. The behavioral strategies employed by desert animals are a testament to the power of evolution, and a reminder that life can find a way to thrive even in the most extreme conditions. These behaviors aren’t just about survival; they’re about making the most of a harsh environment, and finding ways to coexist with the challenges it presents. Understanding these adaptations is crucial not only for appreciating the beauty and complexity of desert ecosystems, but also for conserving them in the face of increasing environmental pressures.

Dietary Adaptations and Food Acquisition

The relentless sun and scarcity of resources in desert environments dictate a unique set of challenges for desert animals when it comes to finding and processing food. It’s not simply what they eat, but how they obtain it, and how their bodies are equipped to extract every possible nutrient and, crucially, water, from their limited diet. The strategies employed are remarkably diverse, ranging from specialized digestive systems to ingenious foraging behaviors. This section will delve into the fascinating world of desert animal diets, exploring herbivory, carnivory, seed predation, and the physiological adaptations that make it all possible.

Herbivory in Arid Environments: Drought-Resistant Plants

For herbivores, the desert presents a particularly difficult proposition. Unlike lush grasslands or forests, deserts offer a sparse and often thorny selection of plant life. These plants, however, are far from passive victims. They’ve evolved their own impressive arsenal of defenses against being eaten, and desert animals that rely on them must be equally resourceful.

Many desert plants are drought-resistant, meaning they’ve developed mechanisms to survive long periods without water. These include deep root systems to tap into groundwater, succulent tissues to store water, and reduced leaf surface area to minimize water loss through transpiration. Examples include cacti, succulents like aloes, and hardy shrubs like acacia and mesquite.

Herbivores have adapted to overcome these challenges. Some, like the Addax antelope of the Sahara, can obtain most of the water they need from the plants they consume, reducing their reliance on scarce water sources. Others, like the desert bighorn sheep, are capable of consuming plants with high salt content, which would be toxic to many other animals. Their kidneys are exceptionally efficient at filtering out excess salt.

The timing of feeding is also crucial. Many desert herbivores are most active during the cooler parts of the day, or even at night, to avoid the intense heat and reduce water loss. They may also selectively browse on plants with higher water content during the driest periods. The ability to digest tough, fibrous plant material is also essential. Many desert herbivores possess specialized gut bacteria that help break down cellulose, the main component of plant cell walls. This symbiotic relationship allows them to extract more nutrients from their food.

The relationship between desert herbivores and plants is often a delicate balance. Overgrazing can lead to desertification, further reducing the availability of food and water. Sustainable grazing practices are therefore essential for maintaining the health of desert ecosystems.

Carnivory and Opportunistic Feeding

A fennec fox a nocturnal predator hunting a kangaroo rat in the Sahara Desert

While plant life may be scarce, deserts are surprisingly rich in animal life, providing a food source for carnivores. However, even for predators, finding a meal in the desert is not easy. Prey animals are often elusive, well-camouflaged, and adapted to avoid detection.

Desert animals that are carnivores have developed a range of strategies to overcome these challenges. Many are opportunistic feeders, meaning they will eat whatever is available, rather than specializing on a single prey species. This flexibility is crucial for survival in an unpredictable environment.

The Fennec Fox, with its enormous ears, is a prime example. These ears not only help dissipate heat but also allow the fox to detect the faint sounds of rodents moving underground. Sidewinder snakes use a unique locomotion style to ambush prey in the sand, while scorpions lie in wait for unsuspecting insects.

Larger predators, such as coyotes and desert foxes, may hunt in pairs or small groups to increase their chances of success. They may also scavenge on carcasses, taking advantage of opportunities when they arise. The ability to travel long distances in search of food is also important. Some desert predators have large territories and may spend hours each day patrolling for prey.

The timing of hunting is also critical. Many desert carnivores are nocturnal, taking advantage of the cooler temperatures and increased activity of their prey. Others may hunt during the early morning or late evening, when the heat is less intense.

The availability of prey can fluctuate dramatically in the desert, depending on rainfall and other environmental factors. Carnivores must be able to adapt to these fluctuations, either by switching to alternative prey species or by reducing their metabolic rate to conserve energy.

Seed Predation and Storage

A kangaroo rat a master of seed storage filling its cheek pouches with seeds

Seeds represent a concentrated source of energy and nutrients, making them a valuable food resource in the desert. However, seeds are often scarce and unpredictable, and many desert plants have evolved mechanisms to protect their seeds from being eaten. This has led to the evolution of specialized seed predators, such as rodents, birds, and insects, that have developed ingenious ways to overcome these defenses.

The Kangaroo Rat is perhaps the most iconic example of a desert seed predator. These small rodents are remarkably well-adapted to life in the desert, obtaining most of the water they need from the seeds they eat. They have specialized cheek pouches for carrying seeds, and they store large quantities of seeds in underground caches. These caches serve as a vital food reserve during times of scarcity.

Ants are also important seed predators in the desert. They collect seeds and carry them back to their nests, where they may eat them or use them to grow fungi. Some ants also disperse seeds, helping to maintain plant diversity.

Birds, such as the Cactus Wren, also play a role in seed predation and dispersal. They feed on seeds and fruits, and they often cache seeds in crevices and under bushes.

Seed predation can have a significant impact on plant populations in the desert. However, it also plays an important role in seed dispersal, helping to maintain plant diversity and resilience. The relationship between seed predators and plants is often a complex one, with plants evolving defenses against predation and predators evolving ways to overcome those defenses.

Specialized Digestive Systems

The harsh conditions of the desert demand exceptional efficiency in nutrient and water extraction. Desert animals have evolved a remarkable array of specialized digestive systems to meet these demands. These adaptations are often closely linked to their diet, reflecting the challenges of processing the available food resources.

Herbivores, as previously mentioned, often rely on symbiotic bacteria in their gut to break down cellulose. However, the specific types of bacteria and the structure of the digestive tract can vary depending on the species and the types of plants they consume. Desert tortoises, for example, have a large cecum, a pouch-like structure that houses bacteria involved in cellulose digestion.

Carnivores, on the other hand, have digestive systems that are optimized for processing protein and fat. They typically have shorter digestive tracts than herbivores, as meat is easier to digest than plant material. They also have a higher concentration of enzymes that break down protein.

Many desert animals have evolved the ability to extract water from their food. The Kangaroo Rat, for example, has highly efficient kidneys that allow it to produce extremely concentrated urine, minimizing water loss. They also have a specialized nasal passage that condenses moisture from their breath.

Some desert animals, such as camels, have unique adaptations for storing water. While the common misconception is that camels store water in their humps, these humps actually store fat, which can be metabolized to produce water. Camels also have the ability to tolerate significant dehydration, losing up to 30% of their body weight in water without experiencing serious health effects.

The efficiency of the digestive system is crucial for survival in the desert. Desert animals that can extract the maximum amount of nutrients and water from their food are more likely to thrive in this challenging environment. These adaptations are a testament to the power of natural selection, shaping the physiology of these creatures to meet the demands of their harsh surroundings. The study of these digestive systems provides valuable insights into the intricate relationship between diet, physiology, and survival in extreme environments.

Unique Adaptations of Specific Desert Animals

The sheer tenacity of life in the desert is a constant source of wonder. It’s easy to look at a seemingly barren landscape and assume it’s devoid of life, but the reality is far more complex. Desert animals aren’t simply surviving in the desert; they’ve been sculpted by it, evolving incredible adaptations that allow them to not just endure, but thrive in conditions that would quickly prove fatal to most other creatures. This section delves into the fascinating specifics of several iconic desert dwellers, showcasing the ingenuity of natural selection.

Camels: The Ships of the Desert

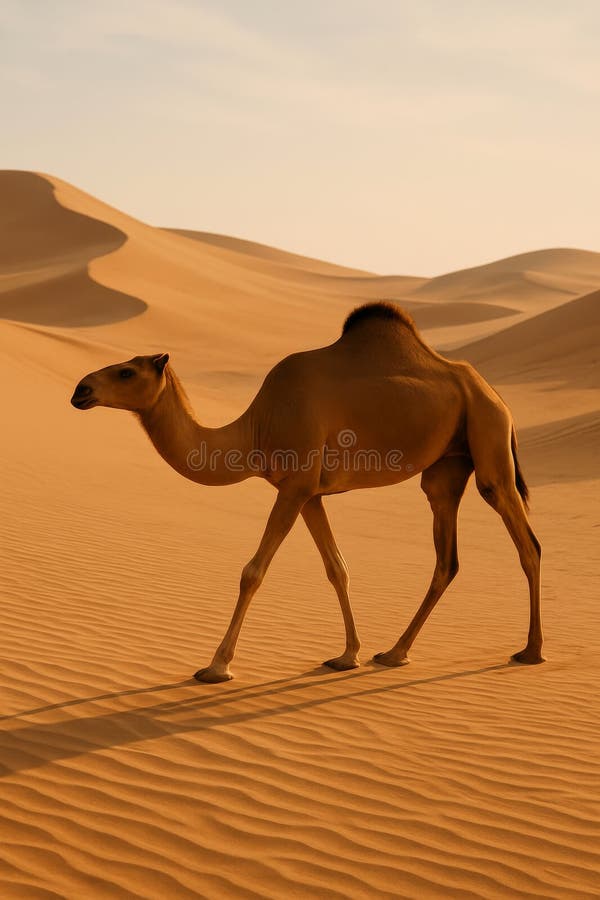

A majestic camel traversing the Sahara perfectly adapted to the harsh environment

The camel, often dubbed the “ship of the desert,” is arguably the most iconic desert animal. Its reputation isn’t just based on its ability to traverse vast distances, but on a suite of remarkable physiological and behavioral adaptations. For centuries, camels have been integral to the lives of nomadic peoples in arid regions, providing transportation, milk, meat, and wool. But what makes them so uniquely suited to this challenging environment?

The most famous adaptation is, of course, the hump. Contrary to popular belief, the hump doesn’t store water. Instead, it’s a reservoir of fat. When food is scarce, the camel metabolizes this fat, providing energy and, crucially, producing water as a byproduct. This metabolic water is a significant contribution to the camel’s hydration. A camel can lose up to 30-40% of its body weight in water without suffering the same consequences as other mammals. This is due to several factors, including their ability to tolerate a wider range of body temperatures (reducing the need to sweat) and their uniquely shaped red blood cells, which remain fluid even when dehydrated, allowing for continued circulation.

Camels also possess a remarkable ability to close their nostrils during sandstorms, preventing sand from entering their respiratory system. Their thick eyelashes and bushy eyebrows provide further protection from the elements. Their broad, padded feet prevent them from sinking into the sand, and their leathery mouths allow them to consume thorny desert vegetation that other animals would avoid. Beyond the physical, camels exhibit behavioral adaptations like seeking shade whenever possible and congregating in groups to minimize exposure to the sun. The relationship between humans and camels is a testament to the animal’s adaptability and resilience, a partnership forged over millennia in the heart of some of the world’s most unforgiving landscapes.

Desert Rodents: Masters of Water Conservation

A kangaroo rat a master of water conservation showcasing its cheek pouches filled with seeds

While camels are the grand symbols of desert survival, the smaller desert rodents often represent the most efficient adaptations. These creatures, including kangaroo rats, gerbils, and pocket mice, have evolved an astonishing array of strategies to minimize water loss and maximize water intake. They are, in many ways, the unsung heroes of the desert animals.

The kangaroo rat is perhaps the most celebrated example. It rarely, if ever, drinks water. Instead, it obtains almost all the moisture it needs from the seeds it consumes. Its highly efficient kidneys concentrate urine to an extraordinary degree, minimizing water excretion. Furthermore, kangaroo rats have a remarkable ability to produce metabolic water, even more efficiently than camels. They also exhibit behavioral adaptations, such as being strictly nocturnal, avoiding the intense daytime heat.

These rodents also construct elaborate burrow systems that provide a cool, humid refuge from the harsh surface conditions. These burrows aren’t just shelters; they’re microclimates, maintaining a stable temperature and humidity level that significantly reduces water loss. The kangaroo rat’s nasal passages are also specially adapted to reclaim moisture from exhaled air, further conserving precious water. Their diet, consisting primarily of dry seeds, might seem counterintuitive, but their digestive systems are incredibly efficient at extracting water from this source. The success of these small rodents highlights the power of subtle, yet profound, adaptations in overcoming environmental challenges.

Desert Reptiles: Scales, Behavior, and Physiology

A desert iguana basking in the sun regulating its body temperature with remarkable efficiency

Reptiles are arguably the most well-represented vertebrate group in desert ecosystems. Their evolutionary history is deeply intertwined with arid environments, and they exhibit a remarkable suite of adaptations that allow them to thrive where other animals struggle. From lizards and snakes to tortoises, desert animals in the reptile family demonstrate a mastery of survival in extreme conditions.

The most obvious adaptation is their scaly skin. These scales are impermeable to water, preventing evaporative water loss. Unlike mammals, reptiles don’t sweat, further reducing water expenditure. Many desert reptiles are ectothermic, meaning they rely on external sources of heat to regulate their body temperature. This allows them to conserve energy, as they don’t need to expend metabolic resources to maintain a constant internal temperature. However, it also means they must carefully manage their exposure to the sun.

Desert reptiles employ a variety of behavioral strategies to regulate their body temperature. Basking in the sun warms them up, while seeking shade or burrowing underground cools them down. Some species, like the desert iguana, can tolerate remarkably high body temperatures. Snakes, in particular, have evolved specialized locomotion strategies to avoid the hot sand, such as sidewinding, which minimizes contact with the ground. Many desert reptiles are also opportunistic feeders, consuming insects, small mammals, and even other reptiles. Their ability to survive for extended periods without food or water makes them incredibly resilient in the face of environmental fluctuations. The Gila monster, one of the few venomous lizards in the world, exemplifies the unique adaptations found within this group.

Desert Birds: Adaptations for Flight and Survival

A roadrunner a fast and agile desert bird demonstrating its hunting prowess

Birds, with their high metabolic rates and need for constant energy, might seem ill-suited to the harsh conditions of the desert. However, a surprising number of bird species have successfully adapted to life in arid environments. These desert animals demonstrate that even demanding physiological requirements can be overcome with clever evolutionary solutions.

Many desert birds are nomadic, following seasonal rainfall patterns and the availability of food. This allows them to exploit ephemeral resources and avoid prolonged periods of drought. They often exhibit behavioral adaptations, such as being most active during the cooler parts of the day, seeking shade, and nesting in sheltered locations. The roadrunner, a well-known resident of the southwestern deserts, is a prime example. Its speed and agility allow it to hunt lizards, insects, and even snakes, while its ability to tolerate high temperatures makes it well-suited to the desert climate.

Desert birds also employ physiological adaptations to conserve water. Some species have highly efficient kidneys that produce concentrated urine. Others can obtain water from their food, such as seeds and insects. Many desert birds also exhibit unique plumage adaptations, such as pale coloration, which reflects sunlight and reduces heat absorption. The cactus wren, for example, builds its nest in cacti, providing protection from predators and the harsh sun. The ability of these birds to fly allows them to cover vast distances in search of food and water, making them remarkably adaptable to the fluctuating conditions of the desert.

Insects and Arachnids: Resilience in Extreme Heat

A desert scorpion a nocturnal predator showcasing its fluorescent exoskeleton under UV light

Often overlooked, insects and arachnids are arguably the most successful animal group in desert ecosystems. Their small size, exoskeletons, and remarkable physiological adaptations allow them to thrive in conditions that would be lethal to larger animals. These tiny desert animals are the foundation of many desert food webs.

The exoskeleton of insects and arachnids is a key adaptation, providing a waterproof barrier that prevents evaporative water loss. Many desert insects are nocturnal, avoiding the intense daytime heat. Others burrow underground, seeking refuge from the sun and accessing cooler, more humid conditions. Some species, like the desert beetle, have evolved specialized structures to collect water from fog or dew.

Scorpions, a particularly iconic group of desert arachnids, are well-adapted to survive in extreme heat and aridity. They have a low metabolic rate, allowing them to conserve energy and water. They also possess a thick exoskeleton and can tolerate dehydration to a remarkable degree. Many desert insects and arachnids exhibit remarkable reproductive strategies, such as laying drought-resistant eggs that can remain dormant for years until conditions are favorable for hatching. The resilience of these small invertebrates highlights the incredible diversity and adaptability of life in the desert, demonstrating that even the smallest creatures can overcome the most challenging environmental obstacles.

The Future of Desert Wildlife

The resilience of desert animals is a testament to the power of adaptation, but even the most finely tuned survival mechanisms are being tested like never before. The future of these incredible creatures hangs in the balance, threatened by forces far greater than the natural challenges they’ve overcome for millennia. It’s a sobering thought, but one that demands our attention and, more importantly, our action. We’ve spent so long marveling at how they survive, we must now focus on ensuring that they survive.

Threats to Desert Ecosystems: Climate Change & Habitat Loss

The twin specters of climate change and habitat loss loom large over desert ecosystems. It’s a cruel irony that environments already defined by scarcity are now facing an acceleration of those very conditions. Climate change isn’t simply making deserts hotter; it’s disrupting the delicate balance that allows life to flourish within them.

Increased temperatures lead to higher evaporation rates, exacerbating water scarcity. This impacts not only the animals directly, but also the vegetation they rely on for food and shelter. Changes in rainfall patterns – more intense but less frequent precipitation – mean that flash floods become more common, eroding fragile soils and disrupting breeding cycles. The subtle shifts in temperature can also disrupt the synchronized life cycles of plants and the desert animals that depend on them. For example, if a flowering plant blooms earlier than usual due to warmer temperatures, the insects that pollinate it may not yet be active, leading to reduced seed production and a ripple effect throughout the food web.

Habitat loss, driven by human activities, is another critical threat. Desert animals are losing their homes to agricultural expansion, urbanization, and resource extraction (mining, oil drilling). Even seemingly small-scale development can fragment habitats, isolating populations and reducing genetic diversity. The construction of roads and fences can impede animal movement, preventing them from accessing vital resources like water sources or breeding grounds. Overgrazing by livestock can degrade vegetation, leading to soil erosion and further habitat loss.

Consider the plight of the Addax, a critically endangered antelope native to the Sahara Desert. Historically roaming vast stretches of the desert, its population has plummeted due to hunting and habitat degradation. The Addax is uniquely adapted to survive in extremely arid conditions, but even its remarkable adaptations are no match for the combined pressures of climate change and human encroachment. Its story is a stark warning of what could happen to other desert animals if we don’t act decisively.

The impact isn’t limited to large mammals. Even seemingly resilient creatures like insects and arachnids are vulnerable. Changes in temperature and humidity can disrupt their life cycles, and habitat loss can reduce their food sources. These smaller creatures play crucial roles in desert ecosystems, as pollinators, decomposers, and prey for larger animals. Their decline can have cascading effects throughout the food web.

Conservation Efforts and Sustainable Practices

Fortunately, the situation isn’t hopeless. A growing awareness of the threats facing desert ecosystems is driving a range of conservation efforts and sustainable practices. These initiatives span from local community-based projects to large-scale international collaborations.

One crucial approach is protected area establishment. National parks, wildlife reserves, and other protected areas provide safe havens for desert animals, safeguarding their habitats from development and exploitation. However, simply establishing protected areas isn’t enough. Effective management is essential, including anti-poaching patrols, habitat restoration, and monitoring of animal populations.

Community-based conservation is also proving to be highly effective. By involving local communities in conservation efforts, we can ensure that they have a vested interest in protecting desert ecosystems. This can involve providing economic incentives for conservation, such as ecotourism opportunities, or supporting sustainable livelihoods that don’t rely on exploiting natural resources. For example, in some parts of the Sahara Desert, local communities are being trained as ecotourism guides, leading visitors on tours to observe wildlife and learn about desert ecology. This provides a sustainable source of income while also promoting conservation awareness.

Sustainable land management practices are also essential. This includes promoting responsible grazing practices, reducing water consumption, and minimizing the use of pesticides and fertilizers. Reforestation efforts, using drought-resistant native plants, can help to restore degraded habitats and provide food and shelter for desert animals.

Technological advancements are also playing a role. Remote sensing technologies, such as satellite imagery and drone surveys, are being used to monitor desert ecosystems, track animal movements, and detect illegal activities like poaching. Genetic research is helping us to understand the genetic diversity of desert animal populations, which is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies.

The reintroduction of species to areas where they have become extinct is another promising conservation tool. However, reintroduction programs must be carefully planned and implemented, taking into account the ecological requirements of the species and the potential impacts on existing ecosystems.

The Importance of Studying Desert Adaptations

Understanding how desert animals survive in such harsh environments isn’t just an academic exercise; it has profound implications for a wide range of fields, from medicine to engineering. The remarkable adaptations that these creatures have evolved offer valuable insights into the limits of life and the potential for innovation.

For example, the efficient kidneys of desert rodents, which allow them to conserve water with incredible efficiency, could inspire new technologies for water purification and desalination. The ability of some desert insects to withstand extreme dehydration could lead to the development of new methods for preserving organs for transplantation. The heat-resistant proteins found in desert reptiles could have applications in industrial processes that require high temperatures.

Studying the behavioral adaptations of desert animals can also provide valuable lessons for human adaptation to climate change. For example, the practice of burrowing to escape the heat could inspire new designs for energy-efficient buildings. The social behavior of meerkats, which involves cooperative cooling, could inform strategies for mitigating the effects of heat waves in urban areas.

Furthermore, studying desert animals provides a unique opportunity to understand the principles of evolution and natural selection. These environments represent extreme selective pressures, driving the evolution of remarkable adaptations. By studying these adaptations, we can gain a deeper understanding of the processes that shape life on Earth.

The field of biomimicry – the practice of learning from and emulating nature’s designs – is increasingly recognizing the potential of desert ecosystems. From the water-collecting scales of the thorny devil lizard to the aerodynamic shape of the sidewinder snake, the desert is a treasure trove of innovative solutions to engineering challenges.

Coexistence and Human Impact

Ultimately, the future of desert animals depends on our ability to coexist with them. We must recognize that these ecosystems are not simply wastelands to be exploited, but valuable natural resources that provide essential ecosystem services, such as water purification, pollination, and climate regulation.

Reducing our environmental footprint is paramount. This includes reducing our consumption of water and energy, minimizing our waste generation, and supporting sustainable businesses. We must also advocate for policies that protect desert ecosystems and promote responsible land management.

Education and awareness are also crucial. By educating the public about the importance of desert ecosystems and the threats they face, we can inspire a sense of stewardship and encourage people to take action. Sharing stories about the incredible desert animals and their adaptations can foster a sense of wonder and appreciation for these unique creatures.

The challenge is significant, but not insurmountable. By embracing a holistic approach that integrates conservation, sustainability, and education, we can ensure that these remarkable desert animals continue to thrive for generations to come. It requires a shift in perspective – from viewing deserts as barren wastelands to recognizing them as vibrant ecosystems teeming with life, worthy of our respect and protection. The fate of these survivors of the harshest environments is, in many ways, a reflection of our own.

Enduring Life in the Sands

The desert. A word that conjures images of endless sand dunes, scorching sun, and a seemingly barren landscape. Yet, beneath this harsh exterior lies a world teeming with life, a testament to the incredible power of adaptation. For millennia, desert animals have not merely survived, but thrived in these extreme environments, showcasing a remarkable resilience that continues to fascinate and inspire. This isn’t just about enduring; it’s about mastering the art of living where others cannot. It’s a story of ingenuity, perseverance, and the beautiful complexity of the natural world.

The Allure and Challenge of Desert Existence

There’s something profoundly captivating about the desert. Perhaps it’s the stark beauty, the vastness that dwarfs our everyday concerns, or the feeling of being connected to something ancient and enduring. But this allure comes with a significant challenge: the desert demands respect. It’s a place where mistakes can be fatal, where resources are scarce, and where survival hinges on a delicate balance.

The core challenges are well-defined. Water is, of course, the most critical. The lack of consistent rainfall and the high rates of evaporation create a constant struggle for hydration. Then there’s the temperature. Deserts experience dramatic temperature swings – blistering heat during the day and often freezing cold at night. This requires animals to regulate their body temperature with incredible precision. Finally, food is often limited and unpredictable. Vegetation is sparse, and finding enough sustenance to fuel activity and reproduction can be a constant quest.

But these challenges aren’t insurmountable. They’ve driven an extraordinary evolutionary process, resulting in a stunning array of adaptations that allow desert animals to not only survive but flourish. It’s a living laboratory of natural selection, where every trait, every behavior, has been honed by the relentless pressures of the environment.

Beyond the Obvious: The Subtle Strategies of Survival

When we think of desert adaptations, we often focus on the dramatic – the camel’s hump, the fennec fox’s enormous ears. And these are certainly important. But the true brilliance of desert survival lies in the subtle, often unseen strategies that animals employ.

Consider the seemingly simple act of seeking shade. It’s not just about escaping the direct sun; it’s about minimizing radiative heat gain. The color of an animal’s fur or scales plays a crucial role. Lighter colors reflect more sunlight, reducing the amount of heat absorbed. Similarly, the shape of the body can influence heat exchange. Animals with larger surface area-to-volume ratios, like the fennec fox, can dissipate heat more effectively.

Then there’s the fascinating world of behavioral thermoregulation. Many desert animals don’t simply tolerate the heat; they actively manipulate their environment to stay cool. This can involve digging burrows, seeking shelter under rocks, or even huddling together in groups to reduce exposure to the sun.

The Water Wizards: Mastering Hydration in Aridity

Water conservation is arguably the most critical adaptation for desert animals. The strategies they employ are remarkably diverse and sophisticated.

Efficient kidneys are a cornerstone of this strategy. Animals like the kangaroo rat can produce incredibly concentrated urine, minimizing water loss through excretion. This is achieved through a complex system of tubules and hormones that reabsorb water back into the bloodstream.

But it’s not just about preventing water loss; it’s also about obtaining it. Some animals, like the kangaroo rat, can derive most of their water from the metabolic breakdown of the seeds they eat. This process, known as metabolic water production, is a remarkable example of biochemical adaptation.

Other animals, like the thorny devil lizard, have specialized skin structures that collect dew and rainwater, channeling it directly to their mouths. This is a passive but highly effective way to supplement their water intake.

The Rhythms of the Desert: Nocturnal Life and Beyond

The desert is a land of extremes, and one of the most effective ways to cope with these extremes is to alter your activity patterns. For many desert animals, this means becoming nocturnal.

By being active at night, animals can avoid the scorching heat of the day and take advantage of cooler temperatures and higher humidity. This shift in activity patterns has profound implications for their physiology and behavior. Nocturnal animals often have enhanced senses of hearing and smell to help them navigate and find food in the dark.

But not all desert animals are strictly nocturnal. Some, like the desert iguana, are active during the day, but they employ a variety of strategies to cope with the heat. These include seeking shade, burrowing, and regulating their body temperature through behavioral means.

Then there’s the phenomenon of estivation, a state of dormancy similar to hibernation, but occurring during the hot, dry season. Some animals, like the lungfish, estivate to conserve energy and water during periods of extreme drought.

A Tapestry of Life: Specific Adaptations in Desert Fauna

Let’s delve into the specific adaptations of some iconic desert animals:

- Camels: Often referred to as the “ships of the desert,” camels are renowned for their ability to survive for long periods without water. Their humps store fat, which can be metabolized to produce water and energy. They also have specialized nostrils that can close to prevent sand from entering, and their thick fur provides insulation against both heat and cold.

- Desert Rodents: Kangaroo rats and other desert rodents are masters of water conservation. They have highly efficient kidneys, can obtain water from seeds, and rarely need to drink. They also have specialized nasal passages that reduce water loss during respiration.

- Desert Reptiles: Reptiles are particularly well-suited to desert life due to their scaly skin, which prevents water loss. They also have behavioral adaptations, such as burrowing and basking, that help them regulate their body temperature.

- Desert Birds: Desert birds, like the roadrunner, have adaptations for flight and survival in arid environments. They often have light-colored plumage to reflect sunlight, and they can obtain water from their food.

- Insects and Arachnids: Insects and arachnids are incredibly resilient creatures that can survive in even the harshest desert conditions. They have exoskeletons that prevent water loss, and they can often burrow underground to escape the heat.

The Future of Desert Wildlife: Threats and Conservation

Despite their remarkable adaptations, desert animals are facing increasing threats. Climate change is exacerbating the already harsh conditions in desert ecosystems, leading to more frequent and intense droughts, heat waves, and wildfires. Habitat loss due to human activities, such as agriculture, urbanization, and mining, is also a major concern.

Conservation efforts are crucial to protect these vulnerable species. These efforts include establishing protected areas, restoring degraded habitats, and implementing sustainable land management practices. It’s also important to raise awareness about the importance of desert ecosystems and the threats they face.

Studying desert adaptations isn’t just about understanding how animals survive in extreme environments; it’s about gaining insights into the fundamental principles of biology and evolution. The lessons learned from desert animals can inform our understanding of how life can adapt to changing conditions, and they can even inspire new technologies and solutions to environmental challenges.

Ultimately, the fate of desert animals is intertwined with our own. By protecting these incredible creatures and their fragile ecosystems, we are not only preserving biodiversity but also safeguarding our own future. The desert is a harsh but beautiful place, and it deserves our respect and protection.

WildWhiskers is a dedicated news platform for animal lovers around the world. From heartwarming stories about pets to the wild journeys of animals in nature, we bring you fun, thoughtful, and adorable content every day. With the slogan “Tiny Tails, Big Stories!”, WildWhiskers is more than just a news site — it’s a community for animal enthusiasts, a place to discover, learn, and share your love for the animal kingdom. Join WildWhiskers and open your heart to the small but magical lives of animals around us!