The silence is deafening. It’s a silence born not of peace, but of absence – the absence of creatures that once roamed, swam, and soared across our planet. Extinction is a natural process, a cornerstone of evolution. But what we’re witnessing today isn’t natural. It’s an acceleration, a heartbreaking cascade of losses driven largely by human activity. We’re losing species at a rate unseen in millennia, and with each disappearance, the intricate web of life unravels a little further. This isn’t just about losing beautiful animals; it’s about destabilizing the very ecosystems that sustain us.

This article delves into the profound impact of animals extinct on the world around them. We’ll journey through specific case studies – from the vanished megafauna of the Pleistocene epoch to the tragically recent loss of the Dodo and the Passenger Pigeon – to understand how the removal of even a single species can trigger cascading effects throughout an ecosystem. We’ll examine the common threads driving these extinctions: habitat destruction, the relentless spread of invasive species, and the increasingly urgent threat of climate change.

We’ll also take a sobering look at more recent losses, considering animals extinct in the wild and even those teetering on the brink – examining what species have sadly gone extinct in animals extinct in 2024 and projecting potential losses for animals extinct in 2025 and animals extinct in 2026. It’s a difficult conversation, but a necessary one. Beyond simply documenting these losses, we’ll explore the critical ecosystem services that are lost when a species disappears – the pollination, seed dispersal, nutrient cycling, and countless other vital functions that underpin a healthy planet.

Ultimately, this isn’t just a post-mortem on past extinctions. It’s a call to action. We’ll explore current conservation efforts, the promise of ecosystem restoration, and what you can do to help protect the incredible biodiversity that remains. Because the fate of these creatures, and ultimately our own, is inextricably linked. The story of animals extinct is a warning, but it’s also an opportunity – a chance to rewrite the ending and build a more sustainable future for all.

Introduction: The Silent Loss

The world hums with life, a complex symphony of interconnected species, each playing a vital role in the delicate balance of our planet’s ecosystems. Yet, beneath this vibrant surface lies a growing silence – the silence of animals extinct, a silence that echoes with the loss of biodiversity and the unraveling of ecological webs. Extinction is not a new phenomenon; it’s a natural part of the evolutionary process. Species have come and gone throughout Earth’s history, replaced by others better adapted to changing conditions. However, the current rate of extinction is anything but natural. It’s a crisis driven by human activity, a sixth mass extinction event unfolding before our very eyes, and it demands our urgent attention. This analysis delves into the profound impact of animals extinct on global ecosystems, examining specific case studies, identifying common threads, and exploring potential pathways towards a more sustainable future.

Defining Extinction and Its Historical Context

Extinction, at its core, is the complete disappearance of a species from Earth. It’s a definitive end, a point of no return. But defining extinction isn’t always straightforward. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) employs a rigorous set of criteria to assess the extinction risk of species, ranging from “Extinct in the Wild” – where a species survives only in captivity – to “Extinct” – where there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. The process of declaring a species extinct often lags behind its actual disappearance, sometimes by decades or even centuries. This is due to the challenges of monitoring remote populations, the difficulty of confirming the absence of a species across its entire range, and the hope, however faint, that a small, undiscovered population might still exist.

Paleontologists excavating a dinosaur fossil illustrating the natural process of extinction over geological time

Historically, extinction events have been linked to catastrophic natural occurrences. The most famous, the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 million years ago, wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs, likely triggered by a massive asteroid impact. Before that, the Permian-Triassic extinction event, often called “The Great Dying,” eliminated an estimated 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. These events reshaped life on Earth, paving the way for the evolution of new species. However, the current extinction crisis is fundamentally different. It’s not driven by a single, dramatic event, but by a multitude of ongoing pressures, all stemming from human activities. The scale and speed of this modern extinction event are unprecedented in Earth’s history, and the consequences are potentially devastating. The recent losses, like those of the Splendid Poison Frog in 2024, serve as stark reminders of this accelerating trend. Understanding this historical context is crucial to appreciating the gravity of the situation and the urgency of conservation efforts. The stories of animals extinct in the wild are not just tales of loss; they are warnings about the future.

The Interconnectedness of Ecosystems

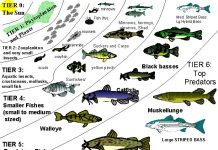

Ecosystems are not simply collections of individual species; they are intricate networks of interactions, where each organism plays a role, and the fate of one is often inextricably linked to the fate of others. This interconnectedness is the foundation of ecosystem stability and resilience. Consider a simple food web: a predator relies on its prey for sustenance, and the prey relies on plants for food. Remove one element from this web, and the consequences can ripple throughout the entire system. The extinction of a keystone species – a species that has a disproportionately large impact on its ecosystem – can trigger a cascade of effects, leading to further extinctions and ecosystem collapse.

A detailed illustration of a rainforest food web showcasing the interconnectedness of species

For example, the loss of large herbivores, like mammoths and mastodons during the Pleistocene extinction, dramatically altered grassland and forest dynamics. These massive animals played a crucial role in maintaining open grasslands by preventing the encroachment of trees. Their disappearance allowed forests to expand, changing the habitat available for other species and impacting nutrient cycling. Similarly, the extinction of the Dodo on Mauritius had profound consequences for seed dispersal and forest regeneration. The Dodo was the only bird capable of dispersing the seeds of certain native trees, and its loss led to a decline in these tree populations and a shift in forest composition. These examples highlight the critical importance of biodiversity and the devastating consequences of losing even a single species. The concept of trophic cascades – where the removal of a top predator leads to an increase in herbivores and a subsequent decrease in vegetation – further illustrates this interconnectedness. The health of an ecosystem is not measured by the number of species it contains, but by the strength and complexity of the relationships between those species. The loss of animals extinct weakens these connections, making ecosystems more vulnerable to disturbance and less able to provide the essential services that humans rely on.

Scope of the Analysis: Global Perspective

This analysis adopts a global perspective, recognizing that the extinction crisis is not confined to any single region or ecosystem. While some areas, like tropical rainforests and coral reefs, are experiencing particularly high rates of biodiversity loss, the impacts of extinction are felt worldwide. We will examine case studies from diverse geographical locations – from the Pleistocene ecosystems of North America and Eurasia to the remote island of Mauritius and the forests of Tasmania – to illustrate the varied causes and consequences of extinction.

A world map highlighting areas of high biodiversity also known as biodiversity hotspots which are particularly vulnerable to extinction

The case studies will focus on species that have become extinct in recent history, or are on the brink of extinction, providing a snapshot of the current crisis. We will explore the specific factors that contributed to their decline, including habitat destruction, invasive species, climate change, and human exploitation. The analysis will also consider the broader ecological impacts of these extinctions, examining how they have affected ecosystem services, such as pollination, seed dispersal, nutrient cycling, and water quality. Furthermore, we will investigate the conservation efforts that have been undertaken to prevent extinction, assessing their successes and failures, and identifying potential strategies for the future. The aim is not simply to document the loss of animals extinct in 2024, animals extinct in 2025, and potential animals extinct in 2026, but to understand the underlying drivers of extinction and to develop effective solutions to address this global challenge. This requires a holistic approach, recognizing that conservation is not just about protecting individual species, but about safeguarding the integrity of entire ecosystems and the well-being of the planet. The scope of this analysis extends beyond the scientific realm, encompassing ethical considerations, economic implications, and the need for collective action to protect biodiversity for future generations.

Case Study 1: The Megafauna Extinction and Pleistocene Ecosystems

The late Pleistocene epoch, spanning roughly 11,700 to 50,000 years ago, witnessed a dramatic and perplexing event: the widespread extinction of megafauna – large animals, often exceeding 100 pounds in weight – across multiple continents. This wasn’t a gradual decline; it was a relatively rapid unraveling of ecological structures that had persisted for millennia. Understanding this extinction event is crucial, not just for historical context, but for illuminating the potential consequences of current biodiversity loss. It serves as a stark warning about the fragility of ecosystems and the profound impact even a few keystone species can have. The story of the disappearing mammoths and mastodons, alongside their contemporaries, is a tale of climate change, human influence, and the intricate web of life.

The Disappearance of Mammoths and Mastodons

A remarkably preserved Woolly Mammoth skeleton on display illustrating the sheer size of these extinct creatures

The image of a woolly mammoth – a colossal, shaggy beast roaming the icy landscapes of the Pleistocene – is iconic. These magnificent creatures, along with their close relatives, the mastodons, were dominant herbivores in North America, Europe, and Asia. Mammoths were adapted to cold, dry environments, possessing thick fur, layers of subcutaneous fat, and curved tusks used for foraging in snow and ice. Mastodons, while also large and possessing tusks, were more adapted to forested environments, browsing on leaves and twigs. Their teeth, unlike the ridged teeth of mammoths designed for grinding grasses, were suited for crushing vegetation.

The timing of their disappearance varies geographically. In North America, the majority of megafauna extinctions occurred around 11,000 years ago, coinciding with the arrival of the Clovis culture – the earliest widespread archaeological culture in North America. However, isolated populations of mammoths persisted on islands like Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean until as recently as 4,000 years ago. This suggests a complex interplay of factors, rather than a single, continent-wide event.

The causes of their extinction have been hotly debated. For a long time, the “overkill hypothesis” – the idea that early humans hunted these animals to extinction – was the dominant theory. Evidence of mammoth bones bearing cut marks from human tools certainly supports this idea. However, the sheer scale of the extinctions, and the fact that some species disappeared even in areas with limited human presence, suggests that other factors were at play. Climate change, specifically the end of the last glacial period and the subsequent warming trend, is now recognized as a significant contributor. The changing climate altered vegetation patterns, reducing the availability of suitable habitat for these large herbivores. It’s increasingly understood that the extinction wasn’t solely due to humans or climate change, but a synergistic combination of both. A stressed population, already struggling with habitat loss due to climate shifts, would have been far more vulnerable to hunting pressure. The story of these animals extinct is a complex one, and the truth likely lies in a nuanced understanding of these interacting forces.

Impact on Grassland and Forest Dynamics

A reconstruction of a Pleistocene grassland ecosystem showcasing mammoths grazing alongside other megafauna

The disappearance of mammoths and mastodons wasn’t simply the loss of a few large animals; it fundamentally altered the structure and function of Pleistocene ecosystems. These animals were not passive consumers; they were ecosystem engineers, actively shaping their environment. Mammoths, in particular, played a crucial role in maintaining the vast grasslands – often referred to as “mammoth steppes” – that characterized much of North America and Eurasia during the Pleistocene.

Their feeding habits – trampling vegetation, breaking trees, and dispersing seeds – prevented the encroachment of forests. By knocking down trees and disturbing the soil, they created a mosaic of habitats, promoting biodiversity. Their dung acted as a fertilizer, enriching the soil and supporting plant growth. Furthermore, their movements created pathways for water flow, influencing drainage patterns and preventing the formation of stagnant wetlands.

With the decline of mammoth populations, these grasslands began to transition into forests and shrublands. The loss of grazing pressure allowed trees to establish themselves, altering the albedo (reflectivity) of the landscape and potentially accelerating warming. This shift in vegetation had cascading effects on other species, impacting everything from insect communities to bird populations. The change in landscape also affected fire regimes. Grasslands are more prone to frequent, low-intensity fires, while forests experience less frequent, but more intense, fires. The shift from grassland to forest altered the frequency and intensity of fires, further shaping the ecosystem. The impact wasn’t limited to the immediate environment; it extended to regional climate patterns. The loss of the mammoth steppes contributed to a feedback loop, accelerating the transition to a warmer, wetter climate. The story highlights how the removal of a single keystone species can trigger a dramatic and lasting transformation of an entire biome.

Cascading Effects on Predator-Prey Relationships

A Smilodon Sabertoothed cat skeleton in a predatory pose illustrating the powerful predators that coexisted with megafauna

The extinction of megaherbivores like mammoths and mastodons didn’t occur in isolation. It triggered a cascade of effects throughout the food web, impacting predator populations and altering predator-prey dynamics. Many predators of the Pleistocene, such as the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon), the dire wolf (Canis dirus), and the short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), were specialized hunters of large prey. These predators were physically adapted to take down massive animals, possessing powerful jaws, strong claws, and robust skeletons.

The disappearance of their primary food source led to a decline in predator populations. Smilodon, for example, relied heavily on mammoths and mastodons for sustenance. Without these large herbivores, they were unable to sustain their populations and eventually went extinct. The dire wolf, while also scavenging, likely depended on the carcasses left by other predators, and its decline mirrored that of its prey. The short-faced bear, a formidable predator and scavenger, also suffered from the loss of megafauna.

However, the story isn’t simply one of predator decline. The loss of large herbivores also created opportunities for smaller predators and scavengers. Species that were previously outcompeted by the larger predators may have benefited from the reduced competition. The ecological niche vacated by the megafauna was eventually filled by other species, but the resulting ecosystem was fundamentally different from the one that existed before. The predator-prey relationships were restructured, and the overall biodiversity of the ecosystem was reduced. The extinction of these animals extinct in the wild wasn’t just a loss of individual species; it was a disruption of the intricate balance of nature, with consequences that reverberated throughout the entire ecosystem. The ripple effects of these extinctions continue to be felt today, shaping the landscapes and ecosystems we see around us. The study of these past events provides invaluable insights into the potential consequences of current biodiversity loss and underscores the urgent need for conservation efforts. The fate of these magnificent creatures serves as a poignant reminder of the interconnectedness of life and the responsibility we have to protect the planet’s remaining biodiversity.

Case Study 2: The Dodo and the Mauritian Ecosystem

Historical Overview of the Dodo

The story of the dodo ( Raphus cucullatus ) is arguably the most iconic tale of animals extinct due to human activity. It’s a narrative steeped in symbolism – a cautionary tale of naiveté, exploitation, and the devastating impact of introducing foreign elements into a fragile ecosystem. The dodo wasn’t a creature of myth, despite its often-caricatured depiction. It was a real bird, a flightless member of the pigeon and dove family, endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean.

A classic 19thcentury illustration of the dodo showcasing its plump form and distinctive beak

Mauritius, before the arrival of humans, was a paradise. A volcanic island rising from the ocean, it had evolved in isolation, fostering a unique biodiversity. The dodo thrived in this environment, a large bird, estimated to weigh between 10-18 kg (22-40 lbs), perfectly adapted to a life without natural predators. Its diet consisted primarily of fruits, seeds, roots, and bulbs. Fossil evidence suggests the dodo was a relatively long-lived bird, perhaps reaching 60-80 years old. Early accounts from sailors, though often exaggerated, describe a bird that was unafraid of humans, allowing them to approach closely. This lack of fear, a consequence of its evolutionary history, would ultimately prove to be its downfall.

The first recorded sighting of the dodo by Europeans was in 1598, by Dutch sailors. These sailors, and those who followed from other European nations, quickly recognized the dodo as a source of food. While the meat wasn’t described as particularly palatable – often described as tough and greasy – it was readily available and easy to catch. The dodo’s lack of fear, combined with its inability to fly, made it an easy target. However, hunting alone wasn’t the sole driver of its extinction. The dodo’s story is inextricably linked to the arrival of other species brought by these ships – a wave of ecological disruption that would forever alter the Mauritian landscape. The initial impact of these early encounters might seem minor, a few birds taken for sustenance, but it was the beginning of a cascade of events that would lead to the complete disappearance of this unique creature within less than a century. The speed of the dodo’s demise is particularly shocking, a stark reminder of how quickly ecosystems can unravel when faced with unprecedented pressures. It’s a poignant example of how even seemingly robust species can be vulnerable when confronted with a novel and overwhelming threat. The dodo’s story isn’t just about a bird; it’s about the fragility of island ecosystems and the devastating consequences of unchecked human impact.

The Role of Introduced Species and Habitat Loss

The arrival of humans on Mauritius wasn’t just about the direct exploitation of the dodo for food. It was the introduction of a whole suite of new species – rats, pigs, monkeys, dogs, cats, and various plants – that truly sealed the dodo’s fate. These introduced species, often unintentionally brought aboard ships, wreaked havoc on the delicate Mauritian ecosystem.

Rats, in particular, proved to be a catastrophic threat to the dodo’s reproductive success. Dodos laid their eggs on the ground, in simple nests, making them incredibly vulnerable to predation. Rats readily consumed these eggs, significantly reducing the number of dodo chicks that survived to adulthood. Pigs and monkeys also preyed on dodo eggs and young, further exacerbating the problem. The introduced animals didn’t just target the dodo’s eggs; they also competed with the dodo for food resources. Pigs, for example, rooted around in the forest floor, consuming the fruits, seeds, and roots that formed a significant part of the dodo’s diet.

Alongside the introduction of invasive species, habitat destruction played a crucial role. As human settlements expanded, forests were cleared for timber, agriculture, and livestock grazing. This deforestation reduced the dodo’s available habitat, forcing it into smaller and more fragmented areas. The loss of forest cover also increased the dodo’s vulnerability to predation, as it had fewer places to hide from introduced predators. The combination of predation, competition, and habitat loss created a perfect storm for the dodo. It was a multi-faceted assault on its survival, and the dodo simply couldn’t adapt quickly enough to cope with the rapid changes.

The impact of these introduced species wasn’t limited to the dodo. Many other native Mauritian species also suffered declines and extinctions as a result of the ecological disruption. The story of the dodo is therefore a microcosm of the broader impact of invasive species on island ecosystems worldwide. It demonstrates how even a single introduction can trigger a cascade of negative consequences, leading to the loss of biodiversity and the degradation of ecosystem function. The concept of invasive species as a major driver of animals extinct is powerfully illustrated by the dodo’s tragic fate. The situation highlights the importance of biosecurity measures – preventing the introduction of non-native species – to protect vulnerable ecosystems. The dodo’s story serves as a stark warning about the unintended consequences of human actions and the need for careful consideration of the ecological impacts of introducing species to new environments.

Consequences for Seed Dispersal and Forest Regeneration

The extinction of the dodo wasn’t just a loss of a single species; it had cascading effects throughout the Mauritian ecosystem, particularly impacting seed dispersal and forest regeneration. The dodo, as one of the few large frugivores (fruit-eaters) on the island, played a vital role in dispersing the seeds of many native trees and plants.

Dodos consumed fruits, and the seeds would pass through their digestive system, effectively scarifying them and preparing them for germination. More importantly, the dodo would often carry these seeds considerable distances before depositing them in their droppings. This process of seed dispersal was crucial for maintaining the genetic diversity of plant populations and for facilitating forest regeneration. With the dodo’s extinction, this vital seed dispersal mechanism was lost.

The seeds of certain tree species, particularly those with large, hard shells, were particularly reliant on the dodo for dispersal. Without the dodo, these seeds struggled to germinate, leading to a decline in the populations of these trees. This decline, in turn, had further consequences for the ecosystem, as these trees provided habitat and food for other species.

Interestingly, recent research has revealed that one particular tree, the Calvaria major, was almost entirely dependent on the dodo for seed dispersal. This tree, which produces a large, hard-shelled fruit, experienced a dramatic decline in numbers after the dodo’s extinction. For centuries, very few new Calvaria major trees were able to grow, and the species was on the brink of extinction itself. It wasn’t until the 1970s that scientists realized the connection between the dodo’s extinction and the Calvaria major’s decline. They discovered that the tree’s seeds could only germinate after passing through the digestive system of the dodo – or, surprisingly, through the digestive system of turkeys, which were introduced to the island as a substitute.

The dodo’s extinction serves as a powerful example of co-evolution – the process by which two species evolve in response to each other. The dodo and the Calvaria major had evolved a mutually beneficial relationship, with the dodo relying on the tree for food and the tree relying on the dodo for seed dispersal. The disruption of this relationship had devastating consequences for both species. The story underscores the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the importance of preserving all species, even those that may seem insignificant. The loss of a single species, like the dodo, can trigger a cascade of effects that ripple throughout the ecosystem, leading to further declines and extinctions. The dodo’s legacy is a reminder that animals extinct aren’t simply gone; their absence leaves a void that can have profound and lasting consequences for the natural world. The case of the dodo and the Calvaria major is a compelling illustration of how the extinction of one species can disrupt fundamental ecological processes, such as seed dispersal and forest regeneration, ultimately impacting the health and resilience of the entire ecosystem. It’s a sobering reminder of the delicate balance of nature and the importance of protecting biodiversity.

Case Study 3: The Passenger Pigeon and North American Forests

The Abundance and Sudden Decline of the Passenger Pigeon

The story of the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) is arguably the most dramatic example of a species driven to extinction by human activity in North American history. It’s a tale of unimaginable abundance followed by a shockingly rapid collapse, a cautionary narrative that continues to resonate with conservationists today. Before European colonization, the Passenger Pigeon was the most abundant bird on the continent, possibly the most abundant vertebrate on Earth. Estimates vary wildly, but credible accounts suggest a population numbering in the billions – some researchers propose between 3 and 5 billion individuals. Imagine flocks so vast they darkened the sky for hours, even days, as they passed overhead. These weren’t just large flocks; they were moving forests of birds, a living, breathing cloud that blocked out the sun.

These flocks weren’t random occurrences. They were dictated by the pigeon’s breeding strategy and the availability of food. Passenger Pigeons were colonial nesters, requiring massive stands of mature forests with specific tree species – primarily beech, oak, and chestnut – to support their enormous colonies. They would congregate in these areas, sometimes covering dozens of square miles, and lay a single egg per nest. The sheer density of nests was astounding. The birds’ nomadic lifestyle was driven by the fluctuating availability of mast – the nuts and seeds produced by these trees. They would move across the eastern and central United States and Canada, following the ripening of these food sources. This nomadic behavior, while successful for millennia, ultimately contributed to their downfall.

The decline began in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, initially a slow creep as forests were cleared for agriculture and settlements. However, the real devastation began with the advent of commercial hunting in the mid-19th century. The pigeons were considered a cheap and readily available food source, and the scale of the hunting was unprecedented. Railroads facilitated access to previously remote nesting grounds, and telegraphs allowed hunters to track the movements of the flocks. Professional pigeoners used nets, guns, and even sulfur fumes to kill vast numbers of birds. The birds were shipped to eastern cities by the train carload, becoming a staple food for the poor. It wasn’t just the hunting itself, but the efficiency of the hunting that proved so catastrophic. The pigeons’ colonial nesting behavior made them incredibly vulnerable. A single, successful raid on a nesting colony could wipe out a significant portion of the population.

The mindset of the time is difficult to comprehend today. There was a widespread belief that the Passenger Pigeon population was inexhaustible. People simply couldn’t fathom that such a seemingly limitless resource could be depleted. This hubris, coupled with the economic incentives of the pigeon trade, fueled the relentless exploitation. The last large-scale nesting colony was recorded in 1878 in Wisconsin, and by the 1890s, the species was on the brink of extinction. Martha, the last known Passenger Pigeon, died at the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914, marking the official end of the species. The speed of the decline is truly staggering – from billions to zero in a matter of decades. This is a stark reminder of how quickly even the most abundant animals extinct can disappear.

Impact on Forest Composition and Nutrient Cycling

The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon wasn’t just a loss of a single species; it was a disruption of complex ecological processes that had been in place for millennia. The pigeons played a crucial role in shaping the composition and health of North American forests, particularly those dominated by oak, beech, and chestnut trees. Their primary role was as a seed disperser, but their impact extended far beyond that.

As nomadic foragers, Passenger Pigeons consumed vast quantities of mast – acorns, beechnuts, and chestnuts. They didn’t digest the seeds, however. Instead, they transported them over long distances in their crops and gizzards, effectively dispersing them across the landscape. This dispersal was particularly important for trees that relied on animal dispersal for regeneration. The pigeons’ movements created a mosaic of forest patches, promoting genetic diversity and resilience within tree populations. They essentially acted as a mobile seed bank, ensuring the continued propagation of these key forest species.

A Passenger Pigeon foraging for acorns demonstrating its role as a seed disperser

Beyond seed dispersal, the pigeons also contributed significantly to nutrient cycling. Their droppings, or guano, were incredibly rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, essential nutrients for plant growth. The massive concentrations of pigeons in nesting colonies resulted in localized “hotspots” of nutrient enrichment, boosting the productivity of the surrounding forest. The sheer volume of guano deposited annually by billions of pigeons would have had a substantial impact on soil fertility and forest health.

The loss of the Passenger Pigeon had cascading effects on forest ecosystems. Without their seed dispersal services, the regeneration of oak, beech, and chestnut trees declined. This shift in forest composition favored other tree species, altering the overall structure and function of the forest. The decline in nutrient cycling likely reduced forest productivity and resilience to disturbances such as drought and insect outbreaks. Some researchers hypothesize that the loss of the pigeons contributed to the decline of the American Chestnut, which was already facing threats from chestnut blight, by reducing its ability to adapt and regenerate. The impact wasn’t immediate or easily observable, but it was a subtle yet significant disruption of the delicate balance of the forest ecosystem. The disappearance of these animals extinct in the wild left a void that continues to be felt today.

Furthermore, the pigeons’ foraging behavior likely influenced the distribution of fungal communities in the forest. By disturbing the soil and spreading fungal spores, they may have played a role in maintaining the health and diversity of mycorrhizal networks – the symbiotic relationships between fungi and plant roots that are essential for nutrient uptake. The loss of this disturbance regime could have had long-term consequences for forest health and resilience. The intricate web of interactions between the Passenger Pigeon and its forest environment highlights the importance of considering the broader ecological context when assessing the impact of extinction.

Lessons Learned from a Rapid Extinction Event

The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon is a powerful and heartbreaking lesson in the consequences of unchecked exploitation and the importance of understanding ecological interconnectedness. It serves as a stark warning about the fragility of even the most abundant species and the potential for rapid, catastrophic declines. Several key lessons emerge from this tragic story.

Firstly, the Passenger Pigeon’s demise demonstrates the dangers of assuming that a resource is inexhaustible. The prevailing belief that the pigeon population was limitless blinded people to the warning signs of decline. This highlights the need for careful monitoring of wildlife populations and a precautionary approach to resource management. We must move beyond the assumption of abundance and embrace a more sustainable mindset.

Secondly, the story underscores the importance of considering the ecological role of a species. The Passenger Pigeon wasn’t just a source of food; it was a keystone species that played a vital role in maintaining the health and resilience of North American forests. Its extinction had cascading effects on forest composition, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity. This emphasizes the need to understand the complex interactions within ecosystems and to protect not just individual species, but the entire ecological web. The loss of animals extinct is rarely isolated; it triggers a ripple effect that can destabilize entire ecosystems.

A somber museum display of Passenger Pigeon skeletons a poignant reminder of their extinction

Thirdly, the Passenger Pigeon’s extinction highlights the devastating impact of commercial exploitation driven by economic incentives. The relentless hunting of the pigeons was fueled by the demand for cheap meat and the profits generated by the pigeon trade. This underscores the need for regulations and policies that prioritize conservation over short-term economic gains. We must find ways to balance human needs with the needs of the natural world.

Finally, the story of the Passenger Pigeon serves as a powerful call to action. It reminds us that extinction is not inevitable and that we have the power to prevent future tragedies. By supporting conservation efforts, advocating for stronger environmental policies, and making sustainable choices in our daily lives, we can help protect the remaining biodiversity on our planet. The lessons learned from the Passenger Pigeon’s extinction are particularly relevant today, as we face a global biodiversity crisis and an accelerating rate of species loss. The fate of countless other species may depend on our ability to learn from the mistakes of the past and to act decisively to protect the future. The story of the Passenger Pigeon is a tragedy, but it is also a catalyst for change. It’s a reminder that the loss of animals extinct in 2024, animals extinct in 2025, and potentially animals extinct in 2026 are not just statistics; they are warnings.

Case Study 4: Thylacine and Tasmanian Ecosystem

The History and Extinction of the Tasmanian Tiger

The story of the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), often referred to as the Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Wolf, is a haunting tale of persecution, misunderstanding, and ultimately, extinction. It’s a case study that resonates deeply with the broader narrative of animals extinct and serves as a stark warning about the consequences of human interference in natural ecosystems. Unlike many extinction stories rooted in habitat loss, the thylacine’s demise is almost entirely attributable to direct human persecution, fueled by economic interests and unfounded fears.

A rare photograph of a thylacine in its natural habitat showcasing its distinctive stripes

The thylacine wasn’t always confined to Tasmania. Fossil evidence reveals its presence across mainland Australia, New Guinea, and even parts of Asia. However, as humans migrated and settled in Australia, the thylacine gradually disappeared from the mainland, likely due to a combination of competition with the dingo (introduced around 3,000-5,000 years ago) and hunting by Aboriginal Australians. The last confirmed sighting on the mainland was around 1930, though unconfirmed reports persisted for some time. Tasmania, separated from the mainland by the Bass Strait, became the thylacine’s last stronghold.

Here, the story takes a particularly tragic turn. European settlers arrived in Tasmania in the early 19th century, and almost immediately, the thylacine was perceived as a threat to livestock, particularly sheep. This perception, whether entirely accurate or not, ignited a relentless campaign to eradicate the animal. A government-sponsored bounty system was introduced in 1888, offering rewards for each thylacine killed. This bounty, coupled with widespread hunting driven by fear and a desire to protect economic interests, proved devastatingly effective.

The bounty system wasn’t based on scientific evidence of thylacine predation on sheep. In fact, investigations later revealed that feral dogs were far more responsible for livestock losses. However, the narrative of the thylacine as a sheep-killing menace had taken hold, and the bounty continued until 1909, though some private bounties were paid out even later. The sheer number of thylacines killed during this period is staggering – over 2,000 bounties were claimed. Beyond the official bounty system, countless thylacines were shot, trapped, and poisoned by farmers and settlers.

The last known thylacine in captivity, named Benjamin, died on September 7, 1936, at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. He had lived in captivity for nearly three years, and his death marked a symbolic end to the species. The last confirmed wild thylacine was reportedly shot in 1930 by Wilfred Batty, a farmer in northeastern Tasmania. Despite numerous expeditions and ongoing searches, no definitive evidence of the thylacine’s survival has been found since. The species was officially declared extinct in 1986. The story of the thylacine is a chilling example of how quickly a species can be driven to extinction through targeted persecution, even in the absence of compelling evidence of genuine threat. It’s a cautionary tale that underscores the importance of evidence-based conservation and the dangers of acting on fear and misinformation. The rapid decline and ultimate disappearance of this unique marsupial serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of life and the devastating impact humans can have on the natural world. The case of the thylacine is often cited when discussing animals extinct in the wild and the ethical responsibilities of conservation.

Role as an Apex Predator and Ecosystem Regulator

Before its extinction, the thylacine occupied the role of an apex predator in the Tasmanian ecosystem. Understanding its ecological role is crucial to comprehending the long-term consequences of its disappearance. Unlike most apex predators, the thylacine was a carnivorous marsupial, possessing a unique combination of canine-like and marsupial characteristics. It was a relatively large animal, typically measuring around 100-130 cm in length (excluding the tail) and weighing between 20-30 kg. Its most distinctive feature was the series of dark stripes across its back, hence the name “Tasmanian Tiger.”

The thylacine’s diet was varied, consisting primarily of kangaroos, wallabies, possums, and other native mammals. It was believed to be an opportunistic hunter, employing a combination of stalking and ambush tactics. Its powerful jaws and sharp teeth were well-suited for capturing and killing prey. However, the thylacine wasn’t solely a predator of large mammals. It also consumed smaller animals, birds, and even carrion.

As an apex predator, the thylacine played a vital role in regulating prey populations. By controlling the numbers of herbivores, it helped to maintain the health and balance of the Tasmanian ecosystem. Its presence likely influenced the behavior and distribution of its prey species, preventing overgrazing and promoting biodiversity. The removal of such a significant predator would inevitably have cascading effects throughout the food web.

The thylacine’s role extended beyond simply controlling prey populations. It likely also influenced the behavior of other predators and scavengers. Its presence may have deterred smaller predators from competing for the same resources, and its scavenging activities would have contributed to nutrient cycling within the ecosystem. The thylacine’s impact on the ecosystem wasn’t limited to its direct interactions with other species. Its presence also shaped the landscape through its hunting patterns and its influence on prey distribution.

Some researchers hypothesize that the thylacine’s extinction contributed to the increase in feral cat populations in Tasmania. With the thylacine removed, feral cats faced less competition and predation, allowing their numbers to flourish. This, in turn, has had a devastating impact on native bird and mammal populations, many of which are already threatened. The absence of the thylacine has created an ecological vacuum, allowing other species to proliferate and disrupt the delicate balance of the Tasmanian ecosystem. The story of the thylacine highlights the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the crucial role that apex predators play in maintaining their health and stability. The loss of this apex predator is a prime example of how the extinction of animals extinct can trigger unforeseen and far-reaching consequences.

Long-Term Effects on Prey Populations and Biodiversity

The extinction of the thylacine has had profound and lasting effects on the Tasmanian ecosystem, impacting prey populations, biodiversity, and overall ecosystem function. While pinpointing the exact extent of these effects is challenging, a growing body of evidence suggests that the thylacine’s disappearance has contributed to a range of ecological imbalances.

A Tasmanian devil a current apex predator in Tasmania interacting with a wallaby illustrating the altered predatorprey dynamics after the thylacines extinction

One of the most noticeable effects has been the increase in populations of certain prey species, particularly wallabies and pademelons. Without the thylacine to regulate their numbers, these herbivores have flourished, leading to increased grazing pressure on native vegetation. This overgrazing has resulted in significant changes to forest structure and composition, favoring certain plant species over others. The increased abundance of wallabies has also contributed to soil erosion and reduced habitat quality for other native animals.

The rise in wallaby populations has also had indirect effects on other species. Increased competition for resources has negatively impacted some native mammals and birds, while the altered vegetation structure has reduced habitat availability for species that rely on specific forest types. The thylacine’s extinction has also been linked to the decline of certain bird species, potentially due to increased predation by feral cats and foxes, which have benefited from the absence of a top predator.

The introduction of diseases, such as facial tumor disease in Tasmanian devils, has further complicated the ecological picture. While the thylacine’s extinction didn’t directly cause the emergence of this disease, it may have exacerbated its impact by removing a key predator that could have helped to control the spread of the disease. The Tasmanian devil, now the island’s largest remaining carnivorous mammal, is struggling to cope with the devastating effects of facial tumor disease, and its decline could further disrupt the ecosystem.

The loss of the thylacine has also had implications for genetic diversity. As a unique marsupial predator, the thylacine possessed a distinct genetic makeup that has been lost forever. This loss of genetic diversity reduces the resilience of the Tasmanian ecosystem to future environmental changes. The story of the thylacine serves as a stark reminder of the importance of preserving biodiversity and the potential consequences of species extinction. The long-term effects of its disappearance are still unfolding, and it may take decades or even centuries for the Tasmanian ecosystem to fully recover. The case of the thylacine is a powerful illustration of how the extinction of animals extinct in 2024, animals extinct in 2025, and even those lost in the past, can have cascading effects that ripple through entire ecosystems. The ongoing research into the thylacine’s ecological role and the consequences of its extinction continues to inform conservation efforts and highlight the need for proactive measures to protect threatened species. The legacy of the thylacine is a somber one, but it also serves as a catalyst for change, inspiring a renewed commitment to preserving the planet’s precious biodiversity.

Global Patterns and Common Threads

The story of animals extinct isn’t a series of isolated incidents, but rather a tapestry woven with repeating patterns and interconnected threads. While each extinction event carries its own unique tragedy, a closer examination reveals strikingly similar underlying causes. To truly understand the scale of the biodiversity crisis, we must move beyond individual species losses and identify these overarching drivers. It’s a sobering realization that the fate of the Splendid Poison Frog in Panama, the potential disappearance of the Vaquita, and the historical loss of the Passenger Pigeon are all linked by a handful of pervasive threats. These aren’t random occurrences; they are symptoms of a deeply unbalanced relationship between humanity and the natural world.

Habitat Destruction as a Primary Driver

Perhaps the most significant and readily identifiable driver of extinction is habitat destruction. It’s a brutally simple equation: fewer places to live means fewer animals can survive. This destruction takes many forms, from the large-scale deforestation of rainforests like the Amazon – driven by agriculture, logging, and mining – to the fragmentation of grasslands for urban development and the draining of wetlands for farmland. The sheer scale of habitat loss is staggering. Consider the plight of the orangutans in Borneo and Sumatra. Their forest homes are being decimated to make way for palm oil plantations, pushing these intelligent primates closer and closer to the brink. It’s not just the complete removal of habitat that’s problematic; fragmentation also plays a crucial role. When large, contiguous habitats are broken into smaller, isolated patches, populations become vulnerable to inbreeding, reduced genetic diversity, and increased susceptibility to local extinctions.

The impact isn’t limited to charismatic megafauna. Even seemingly resilient species struggle when their habitat is compromised. Insects, the foundation of many ecosystems, are particularly vulnerable. The loss of wildflowers and native plants due to urbanization and agricultural intensification directly impacts pollinator populations, with cascading effects throughout the food web. We often focus on the dramatic loss of iconic animals extinct, but the silent disappearance of countless invertebrates is equally alarming. The story of the Pygmy Raccoon, recently animals extinct in 2025 due to habitat loss on Cozumel Island, serves as a stark reminder that even species confined to relatively small areas are not immune. The relentless pressure of human development, even on a small island, can be enough to push a species over the edge. It’s a chilling thought that so much biodiversity is being lost not through dramatic events, but through the slow, insidious creep of habitat degradation. The conversion of natural landscapes into monoculture farms, sprawling cities, and industrial zones represents a fundamental reshaping of the planet, and the consequences for wildlife are devastating.

The Role of Invasive Species

While habitat destruction creates the initial vulnerability, invasive species often deliver the final blow. These are organisms – plants, animals, fungi, or even microorganisms – that are introduced to an environment outside their natural range, where they outcompete native species for resources, prey upon them, or introduce diseases to which they have no immunity. The introduction can be accidental, as with ballast water from ships carrying aquatic organisms, or intentional, as with the introduction of the European rabbit to Australia. The consequences are often catastrophic.

The story of the Dodo, a flightless bird endemic to Mauritius, is a classic example. The arrival of humans brought not only direct hunting pressure but also a suite of invasive species – pigs, rats, and monkeys – that preyed on the Dodo’s eggs and young, ultimately driving it to extinction. The Dodo hadn’t evolved defenses against these new predators, making it incredibly vulnerable. Similarly, the brown tree snake, accidentally introduced to Guam after World War II, decimated native bird populations, leading to the extinction of several species.

The problem isn’t limited to islands. In the Great Lakes region of North America, the sea lamprey, an invasive fish from the Atlantic Ocean, wreaked havoc on native fish populations, including lake trout. The zebra mussel, another invasive species, has dramatically altered the ecosystem, filtering out phytoplankton and disrupting the food web. Even seemingly benign introductions can have unforeseen consequences. The introduction of the water hyacinth to Lake Victoria in Africa, initially intended as an ornamental plant, has choked waterways, reduced oxygen levels, and harmed fish populations. The impact of invasive species is often amplified by climate change, as altered environmental conditions can favor the spread of these opportunistic invaders. Controlling and eradicating invasive species is a costly and challenging undertaking, but it’s essential for protecting biodiversity and preventing further animals extinct.

Climate Change and Accelerated Extinction Rates

The specter of climate change looms large over the future of biodiversity, acting as a threat multiplier that exacerbates existing pressures. While past extinction events were often driven by geological or astronomical forces, the current crisis is largely anthropogenic – caused by human activity. The burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes have released vast amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, leading to a rapid increase in global temperatures. This warming trend is already having profound impacts on ecosystems around the world.

Rising sea levels threaten coastal habitats, including mangrove forests and salt marshes, which are critical nurseries for many marine species. Ocean acidification, caused by the absorption of excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, is harming coral reefs, the “rainforests of the sea,” and the countless organisms that depend on them. Changes in precipitation patterns are leading to more frequent and severe droughts in some regions and increased flooding in others, disrupting ecosystems and threatening species survival.

The Tapanuli Orangutan, potentially animals extinct in 2024, faces a particularly precarious future, not only from habitat loss but also from the impacts of climate change on its forest home. The Vaquita, with fewer than 10 individuals remaining, is facing a similar fate, with changing ocean currents and temperatures potentially impacting its prey base. The Northern Bald Ibis, predicted to face collapse in the wild by 2026, is struggling to adapt to changing migration patterns and food availability.

The rate of climate change is unprecedented in recent history, leaving many species with insufficient time to adapt or migrate. Evolutionary processes typically take thousands or even millions of years, but the current warming trend is occurring over decades. This mismatch between the pace of change and the ability of species to respond is driving a wave of extinctions that could rival those of the past. The loss of even a single keystone species can trigger cascading effects throughout an ecosystem, leading to further biodiversity loss. Addressing climate change is not just an environmental imperative; it’s a moral one. The fate of countless species, and ultimately the health of the planet, depends on our ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and transition to a sustainable future. The increasing number of animals extinct in the wild is a stark warning that we are running out of time.

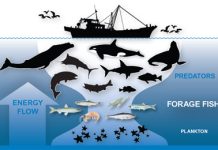

The Ripple Effect: Ecosystem Services Lost

The extinction of a species isn’t an isolated event; it’s a tear in the intricate fabric of life, sending ripples of consequence throughout the ecosystem. These consequences aren’t always immediately apparent, often unfolding over decades or even centuries. We tend to focus on the loss of the animal itself – the majestic tiger, the playful sea otter, the vibrant coral reef fish – but rarely do we fully grasp the cascading effects on the ecosystem services these creatures provide. These services, often taken for granted, are the very foundations of our own survival, and their degradation poses a significant threat to human well-being. The recent wave of animals extinct and those teetering on the brink, particularly those documented as animals extinct in 2024, animals extinct in 2025, and those predicted to be animals extinct in 2026, serve as stark warnings of the potential for widespread ecological disruption.

Pollination and Seed Dispersal Disruptions

A honeybee diligently collecting pollen a vital process for plant reproduction

Perhaps one of the most immediately visible impacts of species loss is the disruption of pollination and seed dispersal. Many plants rely on animals – insects, birds, mammals, even reptiles – to transfer pollen and distribute their seeds. When these animal partners disappear, plant reproduction suffers, leading to declines in plant populations and altered plant communities. Consider the plight of the Splendid Poison Frog ( Oophaga speciosa), recently declared extinct in the wild in Panama. While its vibrant colors and potent toxins are fascinating, its role in the ecosystem extended beyond aesthetics. These frogs, and many other amphibian species, consume insects, helping to control pest populations. But more subtly, they also contribute to seed dispersal by consuming fruits and excreting the seeds in new locations. Their disappearance has a knock-on effect on the forest’s ability to regenerate and maintain its diversity.

The Dodo, a classic example of extinction driven by human activity, provides another compelling illustration. Before its demise on the island of Mauritius, the Dodo played a crucial role in dispersing the seeds of certain native trees. The seeds of these trees required passage through the Dodo’s digestive system to germinate. With the Dodo gone, these trees struggled to reproduce, leading to a decline in their populations and a shift in the forest’s composition. This isn’t just about losing trees; it’s about losing the habitat and food sources for countless other species that depend on those trees. The loss of the Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle, confirmed as extinct in 2025, may seem distant, but even seemingly obscure species can play vital roles in their ecosystems. The intricate web of life means that even the loss of a single thread can unravel larger sections of the tapestry. The decline of bat populations globally, due to habitat loss and disease, is another alarming trend. Bats are crucial pollinators for many plant species, including commercially important crops like agave (used to make tequila!). Their disappearance would have significant economic and ecological consequences. The impact extends beyond the obvious; the loss of pollinators can lead to reduced crop yields, increased food prices, and even food insecurity.

Nutrient Cycling and Soil Health Degradation

Earthworms aerating and enriching the soil essential for nutrient cycling

Beyond pollination and seed dispersal, animals play a critical role in nutrient cycling and maintaining soil health. Many animals, from earthworms to large mammals, contribute to the breakdown of organic matter, releasing essential nutrients back into the soil. This process is fundamental to plant growth and overall ecosystem productivity. The extinction of megafauna, such as mammoths and mastodons during the Pleistocene epoch, had a profound impact on grassland ecosystems. These massive herbivores not only consumed vegetation but also trampled the land, creating disturbances that promoted plant diversity. Their dung served as a rich source of nutrients, fertilizing the soil and supporting a thriving ecosystem. Their disappearance led to changes in grassland composition, with a decline in the abundance of certain plant species and a shift towards more woody vegetation.

The Passenger Pigeon, once the most abundant bird in North America, provides a dramatic example of how the loss of a single species can disrupt nutrient cycling. Billions of these birds once darkened the skies, and their massive flocks deposited enormous amounts of guano (bird droppings) on the forest floor. This guano was a potent fertilizer, enriching the soil with nitrogen and other essential nutrients. The sudden extinction of the Passenger Pigeon resulted in a significant reduction in nutrient input to the forests, potentially impacting tree growth and forest health. Even smaller animals contribute to this process. Vultures, for example, play a vital role in scavenging carcasses, preventing the spread of disease and returning nutrients to the soil. Their decline in many parts of the world has led to an increase in the risk of disease outbreaks and a reduction in nutrient cycling efficiency. The Vaquita, critically endangered and potentially animals extinct in 2026, while a marine mammal, contributes to nutrient cycling in its ecosystem through its feeding habits and eventual decomposition. The loss of apex predators, like the Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger), can also have cascading effects on nutrient cycling. By controlling prey populations, they prevent overgrazing and maintain the health of vegetation, which in turn supports soil health.

Impacts on Water Quality and Carbon Sequestration

The health of ecosystems is inextricably linked to water quality and carbon sequestration, and both are significantly impacted by species loss. Forests, wetlands, and coral reefs all play a crucial role in filtering water, removing pollutants, and maintaining water supplies. Animals contribute to these processes in various ways. Beavers, for example, build dams that create wetlands, which act as natural filters, removing sediment and pollutants from the water. The loss of beavers can lead to increased erosion, sedimentation, and water pollution. Coastal ecosystems, such as mangrove forests and seagrass beds, are particularly important for water quality and carbon sequestration. These ecosystems provide habitat for a wide range of species, including fish, shellfish, and birds, and they also act as nurseries for many commercially important species. The loss of these ecosystems, often driven by habitat destruction and pollution, has devastating consequences for water quality and biodiversity.

Forests are also major carbon sinks, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in their biomass. Animals contribute to carbon sequestration by dispersing seeds, promoting forest growth, and maintaining forest health. The loss of animals can reduce the capacity of forests to absorb carbon dioxide, exacerbating climate change. The Tapanuli Orangutan, potentially animals extinct in 2024, plays a role in seed dispersal within its rainforest habitat, contributing to forest regeneration and carbon storage. The decline of large herbivores can also impact carbon sequestration. By grazing on vegetation, they can stimulate plant growth and increase carbon uptake. However, overgrazing can also lead to soil degradation and reduced carbon storage. The interconnectedness of these processes highlights the importance of maintaining healthy ecosystems and protecting biodiversity. The loss of even a single species can have far-reaching consequences, impacting water quality, carbon sequestration, and ultimately, the health of the planet. The cumulative effect of numerous animals extinct is a weakening of the Earth’s natural systems, making us more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation. The preservation of biodiversity isn’t just an ethical imperative; it’s a matter of our own survival.

Conservation Efforts and Future Outlook

The sobering reality of animals extinct and the accelerating rate of biodiversity loss demands a proactive and multifaceted approach to conservation. It’s not enough to simply mourn the species we’ve lost; we must dedicate ourselves to preventing further extinctions and restoring the health of our planet’s ecosystems. This section will delve into the current strategies employed to safeguard vulnerable species, the critical role of ecosystem restoration, and a passionate call to action for a sustainable future. The weight of responsibility rests on our shoulders, and the time to act is now.

Current Strategies for Preventing Extinction

The fight against extinction is waged on many fronts, employing a diverse toolkit of strategies. These range from direct intervention with endangered populations to tackling the underlying causes of biodiversity loss. One of the most visible and often successful approaches is reintroduction programs. These initiatives involve breeding endangered species in captivity – zoos, wildlife sanctuaries, and specialized breeding facilities – and then carefully releasing them back into their natural habitats. The California Condor is a shining example of this success. Driven to the brink of extinction in the 1980s with only 22 individuals remaining, a dedicated captive breeding program and subsequent reintroduction efforts have brought the population back to over 500 birds, including those soaring freely in the wild.

However, reintroduction isn’t a simple fix. It requires meticulous planning, habitat assessment, and ongoing monitoring. The released animals must be equipped to survive and reproduce in the wild, and the threats that initially drove them to near extinction must be addressed. This often involves tackling issues like habitat destruction, poaching, and human-wildlife conflict.

Alongside reintroduction, captive breeding plays a crucial role, even when immediate release isn’t feasible. Zoos and aquariums are increasingly focused on conservation, not just exhibition. They contribute to genetic diversity by maintaining breeding populations of endangered species, providing valuable research opportunities, and raising public awareness. The success of captive breeding programs hinges on maintaining genetic diversity within the captive population to avoid inbreeding depression and ensure the long-term viability of the species.

Furthermore, gene banks and cloning represent cutting-edge approaches to preserving genetic material. While cloning remains controversial and faces significant technical challenges, it offers a potential lifeline for species with extremely limited genetic diversity. Gene banks, storing sperm, eggs, and tissue samples, provide a safeguard against the complete loss of genetic information, even if a species goes extinct in the wild. This genetic material could potentially be used in future restoration efforts, should the opportunity arise.

But perhaps the most fundamental strategy is strengthening wildlife protection laws and enforcing them effectively. This includes combating poaching, regulating the wildlife trade, and establishing protected areas – national parks, wildlife reserves, and marine sanctuaries – where species can thrive without the immediate threat of human interference. International cooperation is essential, as many endangered species migrate across borders, and illegal wildlife trade is a global problem. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) is a vital tool in regulating this trade, but its effectiveness depends on the commitment of signatory nations.

The recent confirmations of animals extinct in 2024 and the predicted losses for animals extinct in 2025 and animals extinct in 2026 underscore the urgency of these efforts. The Splendid Poison Frog, Lost Shark, and the precarious situation of the Tapanuli Orangutan serve as stark reminders of what’s at stake.

The Importance of Ecosystem Restoration

Protecting individual species is vital, but it’s only part of the solution. The long-term survival of biodiversity depends on restoring the health and functionality of entire ecosystems. Ecosystems are complex webs of interconnected relationships, and the loss of even a single species can have cascading effects throughout the system. Ecosystem restoration involves actively assisting the recovery of degraded, damaged, or destroyed ecosystems. This can take many forms, from reforestation and wetland restoration to coral reef rehabilitation and the removal of invasive species.

Reforestation, for example, isn’t simply about planting trees. It’s about restoring the entire forest ecosystem, including the soil, the understory vegetation, and the animal communities that depend on the forest for survival. Choosing the right tree species is crucial, prioritizing native species that are adapted to the local climate and soil conditions. Furthermore, restoration efforts must address the underlying causes of degradation, such as deforestation for agriculture or logging.

Wetland restoration is equally important. Wetlands – marshes, swamps, and bogs – provide a wealth of ecosystem services, including flood control, water purification, and habitat for a wide range of species. They also act as important carbon sinks, helping to mitigate climate change. Restoring degraded wetlands can involve removing drainage ditches, re-establishing natural water flows, and replanting native vegetation.

Coral reef restoration is a particularly challenging but critical undertaking. Coral reefs are among the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth, but they are highly vulnerable to climate change, pollution, and destructive fishing practices. Restoration efforts can involve growing coral fragments in nurseries and then transplanting them onto degraded reefs. However, the long-term success of coral reef restoration depends on addressing the underlying threats, such as reducing carbon emissions and improving water quality.

The case of the Passenger Pigeon, a species that once numbered in the billions but went extinct in the early 20th century, highlights the importance of understanding ecosystem dynamics. The sudden disappearance of this keystone species had profound impacts on North American forests, altering forest composition and nutrient cycling. Restoring forests to their pre-Passenger Pigeon state is impossible, but understanding the role this species played can inform our restoration efforts today. Similarly, the extinction of the Thylacine in Tasmania had long-term effects on prey populations and biodiversity, demonstrating the importance of apex predators in regulating ecosystems.

The loss of animals extinct in the wild often signals a broader ecosystem decline. Focusing solely on individual species without addressing the health of their habitats is a short-sighted approach.

A Call to Action: Protecting Biodiversity for a Sustainable Future

The challenges facing biodiversity are immense, but they are not insurmountable. Protecting our planet’s incredible array of life requires a collective effort, involving governments, organizations, communities, and individuals. We must move beyond simply acknowledging the problem and embrace a proactive and sustainable approach to conservation.

Governments must prioritize biodiversity conservation in their policies and allocate sufficient resources to support conservation efforts. This includes strengthening environmental regulations, investing in protected areas, and promoting sustainable land use practices. International cooperation is essential, particularly in addressing transboundary conservation issues.

Organizations – both governmental and non-governmental – play a vital role in conducting research, implementing conservation programs, and raising public awareness. They need adequate funding and support to continue their important work.

Communities must be empowered to participate in conservation efforts, recognizing that local communities often have a deep understanding of their ecosystems and a vested interest in their preservation. Sustainable livelihoods that are compatible with conservation goals should be promoted.

But perhaps the most important role lies with individuals. Each of us can make a difference by making conscious choices in our daily lives. This includes supporting wildlife conservation organizations, avoiding products tied to deforestation or poaching, advocating for stronger environmental policies, and educating others about endangered species. Reducing our carbon footprint, conserving water, and minimizing our consumption of resources are all actions that contribute to a more sustainable future.

The fate of countless species, and ultimately the health of our planet, hangs in the balance. We cannot afford to stand idly by while animals extinct at an alarming rate. The time for complacency is over. Let us embrace our responsibility as stewards of the Earth and work together to create a future where biodiversity thrives, and where future generations can experience the wonder and beauty of the natural world. The stories of the Dodo, the Passenger Pigeon, and the Thylacine should serve as cautionary tales, reminding us of the irreversible consequences of inaction. Let us learn from the past and build a future where extinction is no longer a looming threat, but a preventable tragedy.

A World Without: Reflecting on the Consequences

The silence is the most haunting consequence. Not a literal silence, perhaps, though the absence of a species’ song, call, or even rustling through the undergrowth is a palpable loss. It’s a deeper silence – the silencing of evolutionary history, the muting of unique genetic contributions, the diminishing of the planet’s vibrant tapestry of life. To contemplate a world stripped of the animals extinct, particularly those lost in recent years, is to confront a profound and unsettling truth: we are living through a period of unprecedented biodiversity loss, largely driven by our own actions. It’s a sobering realization, and one that demands not just scientific understanding, but also emotional engagement and a renewed commitment to conservation.

The recent losses – the Splendid Poison Frog, the Lost Shark, the potential extinction of the Tapanuli Orangutan – aren’t simply entries in a scientific ledger. They represent the unraveling of intricate ecological relationships, the severing of connections that have taken millennia to forge. Consider the Splendid Poison Frog, once a jewel of the Panamanian rainforest. Its vibrant colors weren’t merely aesthetic; they were a warning, a signal of its toxicity, a crucial element in its defense against predators. Its disappearance doesn’t just mean one less brightly colored frog; it means a disruption in the predator-prey dynamics of its ecosystem, potentially leading to imbalances and unforeseen consequences. The animals extinct in the wild leave behind voids that are difficult, if not impossible, to fill.

The story of the Lost Shark is particularly chilling. Declared extinct due to overfishing, it highlights the devastating impact of human exploitation on marine ecosystems. Sharks, often demonized, are apex predators, playing a vital role in maintaining the health and stability of ocean food webs. Removing a top predator can trigger a cascade of effects, leading to the proliferation of certain species, the decline of others, and ultimately, a less resilient and diverse marine environment. The loss of the Lost Shark is a stark reminder that even seemingly “invisible” species play critical roles in the functioning of our planet.

Looking ahead, the predicted or concerning losses for 2025 and 2026 – the Pygmy Raccoon, the Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle, the Vaquita, the Northern Bald Ibis, and specific subpopulations of the Javan Rhino – paint an even more alarming picture. The Vaquita, with fewer than 10 individuals remaining, is teetering on the brink of oblivion, a tragic consequence of illegal fishing practices. Its story is a desperate plea for immediate and effective conservation action. The plight of the Javan Rhino, facing localized extinction due to habitat loss, underscores the urgent need to protect and restore critical habitats. These aren’t just statistics; they are individual lives, unique evolutionary lineages, and irreplaceable components of our planet’s biodiversity. The potential for animals extinct in 2025 and animals extinct in 2026 to become reality is a constant, looming threat.

But the consequences extend far beyond the immediate loss of species. The disappearance of animals extinct impacts the very ecosystem services that sustain human life. Pollination, seed dispersal, nutrient cycling, water purification, and carbon sequestration – these are all processes that rely on healthy and diverse ecosystems. When species disappear, these services are compromised, with potentially devastating consequences for human well-being.

Consider the role of seed dispersal. Many plants rely on animals to distribute their seeds, ensuring their survival and regeneration. The Dodo, famously extinct due to human activity and introduced species, played a crucial role in dispersing the seeds of certain trees on Mauritius. Its extinction led to a decline in the regeneration of those trees, altering the structure and composition of the forest. Similarly, the Passenger Pigeon, once the most abundant bird in North America, played a significant role in forest dynamics through its feeding and nesting habits. Its rapid extinction had profound impacts on forest composition and nutrient cycling.

The loss of pollinators, like bees and butterflies, is another critical concern. These tiny creatures are responsible for pollinating a vast array of crops, ensuring our food security. Their decline, driven by habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change, poses a serious threat to agricultural productivity and global food supplies. The ripple effects of extinction are far-reaching and often unpredictable.

Furthermore, the loss of biodiversity weakens the resilience of ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to disturbances such as climate change, disease outbreaks, and invasive species. A diverse ecosystem is like a well-diversified investment portfolio – it’s better able to withstand shocks and adapt to changing conditions. A simplified ecosystem, on the other hand, is more fragile and susceptible to collapse.

The concept of “extinct in the wild” – where a species survives only in captivity or controlled environments – is a particularly poignant one. While it represents a temporary reprieve from complete extinction, it also raises ethical questions about the role of humans in manipulating and controlling nature. Species like the Scimitar-horned oryx and Père David’s deer, once roaming freely in their native habitats, now exist primarily as captive populations, dependent on human intervention for their survival. Is this a true victory for conservation, or a symbolic acknowledgment of our failure to protect their natural environments?

The conservation efforts currently underway – reintroduction programs, captive breeding success stories, gene banks, and cloning possibilities – offer a glimmer of hope. The recovery of the California condor, once on the brink of extinction, is a testament to the power of dedicated conservation efforts. However, these efforts are often expensive, time-consuming, and fraught with challenges. They are also, ultimately, a band-aid solution. The most effective way to prevent extinction is to address the underlying causes – habitat destruction, illegal hunting and poaching, climate change, pollution, and invasive species.

We need to move beyond simply reacting to extinction and towards proactively protecting biodiversity. This requires a fundamental shift in our relationship with nature, recognizing that we are not separate from the natural world, but an integral part of it. It requires stronger environmental policies, increased funding for conservation, and a greater awareness of the interconnectedness of all living things.

Each of us has a role to play in protecting biodiversity. We can support wildlife conservation organizations, avoid products tied to deforestation or poaching, advocate for stronger environmental policies, and educate others about endangered species. We can make conscious choices in our daily lives to reduce our environmental footprint and promote sustainable practices. The future of our planet, and the fate of countless species, depends on it.

The world without these animals extinct is a diminished world, a world less vibrant, less resilient, and less beautiful. It’s a world where the silence grows louder, and the consequences of our actions become increasingly apparent. It’s a world we must strive to avoid. The time for action is now.