Ever paused to watch a deer gracefully graze in a meadow, or marvel at the sheer size of an elephant stripping leaves from a tree? These captivating creatures, and countless others, belong to the fascinating world of herbivores animals – the plant-eating species that form a cornerstone of life on Earth. This comprehensive guide is your deep dive into understanding these gentle giants and the surprisingly complex lives they lead.

We often take for granted the simple act of eating, but for herbivorous animals, obtaining nourishment from plants isn’t always easy. It requires incredible adaptations, from specialized teeth and digestive systems to intricate relationships with the microscopic world within their guts. We’ll explore these fascinating characteristics of herbivores and uncover how they’ve evolved to thrive on a plant-based diet.

This isn’t just a list of herbivores; it’s a journey through diverse habitats, showcasing the incredible variety of animals that eat plants. From the towering giraffes of the African savanna to the tiny seed-eating finches flitting through our gardens, we’ll examine examples of herbivores across the mammalian, avian, reptilian, and even insect worlds. We’ll categorize them into types of herbivorous animals – grazers, browsers, frugivores, and more – revealing the nuances of their dietary preferences.

But it goes beyond just what do herbivores eat. We’ll delve into their crucial role in ecosystems, understanding how they act as keystone species, shape plant communities, and maintain the delicate balance between predator and prey. We’ll also confront the challenges they face today – habitat loss, poaching, and the looming threat of climate change – and explore the vital conservation efforts underway to protect these magnificent herbivores animals for generations to come. Prepare to be amazed by the okapi, the manatee, and the eucalyptus-loving koala, and discover why understanding these plant-eating wonders is so essential for the health of our planet.

Defining Herbivores: What Does it Mean to be a Plant-Eater?

To truly understand the world of herbivores animals, we must first define what it means to be a plant-eater. It’s more than just a dietary preference; it’s a lifestyle sculpted by millions of years of evolution, demanding specialized adaptations and playing a critical role in the health of our planet. The very concept of herbivory – deriving sustenance solely or primarily from plants – seems simple enough, yet the intricacies are astonishing. It’s a story of co-evolution, of plants developing defenses and animals evolving ways to overcome them, a constant dance that shapes ecosystems.

The Evolutionary History of Herbivory

The story of herbivory isn’t one of immediate adoption. Life began in the oceans, and the first organisms were likely chemoautotrophs or heterotrophs consuming other organisms. Plants themselves evolved later, and initially, they weren’t particularly appetizing. Early plants lacked the complex defenses we see today, but they were still challenging to digest. The transition to a plant-based diet wasn’t easy. It required significant physiological changes.

Fossil evidence illustrating the evolutionary transition to herbivory

The earliest herbivores were likely invertebrates, insects that began to nibble on primitive plant life. As plants diversified, so did the herbivores. The Cambrian explosion, a period of rapid diversification of life around 540 million years ago, saw the emergence of the first multicellular animals, and with them, the beginnings of herbivorous strategies. However, the real expansion of herbivory occurred with the rise of terrestrial vertebrates.

The Mesozoic Era, the age of dinosaurs, witnessed the evolution of large herbivorous dinosaurs like sauropods (Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus) and ornithopods (Iguanodon, Parasaurolophus). These giants developed massive bodies and specialized teeth for processing vast quantities of vegetation. Their digestive systems, though not fully understood, were clearly adapted for plant matter. The extinction of the dinosaurs paved the way for the rise of mammals, and with them, a new wave of herbivorous innovation. Early mammals were generally small and opportunistic, but over time, they diversified into the wide range of herbivorous animals we see today – from the towering elephants to the diminutive voles. The evolution of flowering plants (angiosperms) in the Cretaceous period further fueled this diversification, offering a wider variety of plant tissues and nutritional resources.

The development of symbiotic relationships with gut microbes was a pivotal moment in the evolutionary history of herbivory. These microbes, residing in the digestive tracts of herbivores, possess enzymes capable of breaking down cellulose, a complex carbohydrate that animals cannot digest on their own. This partnership allowed herbivores to unlock the energy stored in plant cell walls, significantly expanding their dietary options.

Types of Herbivores: Grazers, Browsers, and Frugivores

While all herbivores animals share a common trait – a plant-based diet – the way they consume plants varies considerably. This leads to a useful categorization based on feeding strategies: grazers, browsers, and frugivores. Understanding these distinctions provides insight into the ecological roles these animals play and the adaptations they’ve developed.

- Grazers: These herbivores primarily feed on grasses and other low-growing vegetation. Think of the vast herds of wildebeest on the African savanna, or the domestic cattle in pastures around the world. Grazers typically have high-crowned teeth, adapted for grinding tough, abrasive grasses. Their digestive systems are often large and complex, with multiple chambers to facilitate the breakdown of cellulose. They tend to live in open habitats like grasslands, savannas, and prairies. Examples include: Zebras, horses, cows, sheep, and geese.

A herd of zebras grazing on the open savanna demonstrating a typical grazing behavior

- Browsers: Unlike grazers, browsers feed on leaves, twigs, shoots, and fruits of trees and shrubs. They are often found in forested or woodland environments. Browsers tend to have more selective feeding habits than grazers, choosing specific plant parts based on their nutritional content. Their teeth are often adapted for shearing and tearing leaves, rather than grinding grasses. Examples include: Deer, giraffes, elephants (though they also graze), and goats.

A giraffe browsing on the leaves of an acacia tree showcasing its long neck and specialized feeding habits

- Frugivores: These herbivores specialize in consuming fruits. Fruits are rich in sugars and vitamins, providing a readily available source of energy. Frugivores play a crucial role in seed dispersal, as they often excrete seeds in different locations, helping plants to colonize new areas. They typically have relatively simple digestive systems, as fruits are easier to digest than leaves or grasses. Examples include: Fruit bats, many species of monkeys, toucans, and some parrots.

A colorful toucan enjoying a ripe fruit in the lush rainforest illustrating frugivory

Beyond these three main categories, there are other specialized types of herbivores. Granivores eat seeds (mice, pigeons), nectarivores feed on nectar (hummingbirds, butterflies), and folivores specialize in leaves (koalas, sloths). The specific dietary niche an herbivore occupies is often determined by its anatomy, physiology, and the availability of resources in its environment.

Physiological Adaptations for Plant Digestion

Plants present a unique set of digestive challenges. Unlike animal tissues, plant cell walls are composed of cellulose, a complex carbohydrate that most animals cannot break down on their own. Furthermore, plants often contain secondary compounds – toxins and deterrents – that protect them from being eaten. To overcome these challenges, herbivorous animals have evolved a remarkable array of physiological adaptations.

- Specialized Teeth: The teeth of herbivores are adapted for grinding and shearing plant material. Grazers typically have high-crowned teeth with complex ridges for grinding tough grasses. Browsers have teeth adapted for shearing leaves and twigs. Frugivores often have simpler teeth for crushing fruits.

- Complex Digestive Systems: Many herbivores have evolved complex digestive systems with multiple chambers to increase the surface area for microbial fermentation. Ruminants, such as cows and sheep, have a four-chamber stomach (rumen, reticulum, omasum, abomasum) where bacteria and other microbes break down cellulose. Non-ruminant herbivores, such as horses and rabbits, rely on a large cecum – a pouch at the junction of the small and large intestines – to house their microbial communities.

- Symbiotic Microorganisms: The gut microbiome is arguably the most important adaptation for herbivory. The bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms residing in the digestive tract of herbivores produce enzymes that break down cellulose and other complex plant carbohydrates. They also synthesize essential vitamins and nutrients that the herbivore cannot obtain directly from plants.

- Detoxification Mechanisms: Plants produce a variety of secondary compounds to deter herbivores. These compounds can be toxic or simply make the plant unpalatable. Herbivores have evolved detoxification mechanisms to neutralize these compounds, allowing them to consume plants that would otherwise be harmful. This can involve specialized enzymes in the liver or gut, or behavioral adaptations such as selective feeding.

- Slow Digestion Rates: Plant matter is relatively low in energy density compared to animal tissues. To maximize nutrient extraction, herbivores often have slow digestion rates, allowing more time for microbial fermentation and nutrient absorption. This also means that they need to consume large quantities of food to meet their energy needs.

These adaptations, honed over millions of years of evolution, allow herbivores animals to thrive on a diet of plants, playing a vital role in the functioning of ecosystems around the world. The intricate relationship between plants and herbivores is a testament to the power of natural selection and the interconnectedness of life on Earth.

Major Herbivore Groups and Their Habitats

This section delves into the incredible diversity of herbivores animals across the animal kingdom, categorizing them into major groups based on their class – mammals, birds, reptiles, and insects. We’ll explore their unique adaptations, preferred habitats, and specific examples that showcase the fascinating world of plant-eating wildlife. Understanding these groups provides a broader appreciation for the ecological roles these creatures play and the challenges they face.

Mammalian Herbivores: A Diverse Range

Mammals represent a significant portion of the herbivore population, exhibiting a remarkable range of sizes, behaviors, and adaptations. Their success as plant-eaters is largely due to their complex digestive systems, often involving multiple stomach chambers and symbiotic relationships with gut bacteria.

Deer and Antelope: Masters of Grasslands

A serene scene of deer peacefully grazing in their natural habitat

Deer and antelope, belonging to the family Cervidae and Bovidae respectively, are iconic inhabitants of grasslands, savannas, and forests worldwide. These herbivorous animals are generally characterized by their slender builds, long legs, and graceful movements. Their diet primarily consists of grasses, shrubs, leaves, and twigs. A key adaptation is their ruminant digestive system – a four-chamber stomach that allows them to efficiently break down cellulose, the tough structural component of plants. This process involves regurgitating and re-chewing partially digested food (cud) to further extract nutrients. Different species exhibit varying levels of social behavior, ranging from solitary deer like the roe deer to large herds of wildebeest and gazelle. Antelope, in particular, demonstrate incredible speed and agility, crucial for evading predators in open grasslands. The geographic distribution is vast; North American white-tailed deer thrive in forests, while African gazelles dominate the savannas. Their impact on vegetation is significant, influencing plant community structure and promoting biodiversity. For example, selective grazing can prevent certain plant species from becoming dominant, allowing for a more diverse ecosystem.

Elephants: The Largest Land Herbivores

An African elephant demonstrating its impressive size and feeding behavior

Elephants, the largest land animals on Earth, are truly remarkable plant-eating animals. Found in Africa and Asia, these gentle giants consume an astonishing amount of vegetation daily – up to 150 kg (330 lbs)! Their diet includes grasses, leaves, bark, fruits, and roots. Their trunk is a versatile tool, used for grasping food, drinking water, and even communicating. Elephants possess large, flat molars that are continuously replaced throughout their lives, essential for grinding tough plant material. Like deer and antelope, they have a relatively inefficient digestive system, meaning they only extract about 40% of the nutrients from their food. This necessitates their massive intake. Elephants play a crucial role in shaping their environment. They create clearings in forests by knocking down trees, which promotes new growth and creates habitats for other species. Their dung also serves as a valuable fertilizer and seed disperser. The African elephant ( Loxodonta africana) and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) differ in size, ear shape, and other characteristics, reflecting their adaptation to different environments. Sadly, both species face significant threats from habitat loss and poaching.

Rhinoceroses: Horned Giants of Africa and Asia

A white rhinoceros peacefully grazing showcasing its powerful build and distinctive horn

Rhinoceroses, characterized by their thick skin and prominent horns, are another group of large mammalian herbivores. Five species exist, found in Africa and Asia. Their diet varies depending on the species, ranging from grasses and leaves to shrubs and branches. Black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis) are browsers, preferring leaves and twigs, while white rhinoceroses (Ceratotherium simum) are grazers, specializing in grasses. Like elephants, rhinoceroses have relatively inefficient digestive systems. Their horns are made of keratin, the same material as human fingernails, and are used for defense, dominance displays, and foraging. Unfortunately, rhinoceroses are critically endangered due to poaching, driven by the demand for their horns in traditional medicine. Conservation efforts are crucial to protect these magnificent creatures and their habitats. Their grazing and browsing habits also influence vegetation structure, creating mosaics of different habitats.

Horses and Zebras: Equine Adaptations

A herd of zebras grazing on the African savanna displaying their distinctive stripes

Horses and zebras, belonging to the family Equidae, are well-adapted to life on grasslands and savannas. Their long legs and strong hooves allow them to cover large distances in search of food. They are primarily grazers, feeding on grasses and other herbaceous plants. Their digestive system is designed for a continuous intake of low-quality forage. They have a large cecum, a pouch in the large intestine, where bacteria ferment plant material. Zebras are native to Africa, while horses have a wider distribution, having been domesticated by humans for thousands of years. Their social structure typically involves herds, providing protection from predators. The distinctive stripes of zebras are thought to serve multiple purposes, including camouflage, insect repellent, and social signaling. Wild horses, such as the Przewalski’s horse, are endangered and require conservation efforts to maintain their genetic diversity.

Avian Herbivores: Birds with a Plant-Based Diet

While often overlooked, birds represent a diverse group of herbivorous animals, with many species specializing in plant-based diets. Their adaptations for feeding on plants vary depending on the type of plant material they consume.

Seed-Eating Finches and Sparrows

A goldfinch expertly extracting seeds from a thistle flower

Finches and sparrows are classic examples of granivorous birds – those that primarily eat seeds. They possess strong, conical beaks adapted for cracking open seeds. Their digestive systems are efficient at processing seeds, with a well-developed gizzard that grinds the seeds to aid digestion. These birds play an important role in seed dispersal, contributing to plant reproduction. They are commonly found in a variety of habitats, including grasslands, forests, and urban areas. Different species have evolved specialized beak shapes and feeding behaviors to exploit different types of seeds.

Fruit-Eating Parrots and Toucans

A vibrant scarlet macaw enjoying a ripe mango showcasing its powerful beak

Parrots and toucans are renowned for their vibrant colors and their preference for fruits. They have strong, hooked beaks that are ideal for tearing open fruits and accessing the seeds and pulp inside. Their digestive systems are adapted to handle the sugars and nutrients found in fruits. They are important seed dispersers, particularly in tropical rainforests. Their bright plumage often serves as camouflage in the dense foliage of their habitat. They are highly intelligent birds, often exhibiting complex social behaviors.

Reptilian Herbivores: Less Common, But Fascinating

Herbivory is less common among reptiles compared to mammals and birds, but several species have successfully adapted to a plant-based diet.

Iguanas: Specialized Leaf Eaters

Iguanas, particularly the green iguana (Iguana iguana), are well-known for their herbivorous habits. They are primarily folivores, feeding on leaves, flowers, and fruits. They possess strong jaws and sharp teeth adapted for tearing and grinding plant material. Their digestive system is relatively long, allowing for efficient extraction of nutrients from leaves. They are arboreal, spending most of their time in trees. They are found in Central and South America and the Caribbean.

Insect Herbivores: The Most Abundant Plant Consumers

Insects represent the most diverse and abundant group of herbivores animals on Earth. Their impact on plant communities is immense.

Caterpillars: Leaf-Devouring Machines

A caterpillar diligently consuming a leaf demonstrating its voracious appetite

Caterpillars, the larval stage of butterflies and moths, are notorious for their leaf-eating habits. They possess strong mandibles (jaws) adapted for chewing leaves. They grow rapidly, molting their skin several times as they increase in size. They play a significant role in plant herbivory, and some species can cause significant damage to crops and forests.

Grasshoppers and Locusts: Swarming Herbivores

Grasshoppers and locusts are voracious feeders on grasses and other plants. They possess strong legs for jumping and chewing mouthparts for consuming vegetation. Locusts, in particular, are known for their ability to form massive swarms, which can devastate crops and grasslands. Their swarming behavior is triggered by environmental conditions and population density.

This exploration of major herbivore groups highlights the incredible diversity and adaptability of herbivorous animals across the globe. Each group has evolved unique strategies for obtaining and digesting plant material, playing a vital role in maintaining the health and balance of ecosystems.

Dietary Strategies and Nutritional Needs

The world of herbivores animals is a fascinating study in adaptation. While the concept of simply “eating plants” seems straightforward, the reality is incredibly complex. Plants, unlike meat, are notoriously difficult to digest. They are encased in tough cell walls, often contain toxins, and provide a relatively low energy yield compared to animal protein. This section will delve into the challenges herbivores face in extracting nutrients from their plant-based diets, the remarkable symbiotic relationships they’ve evolved to overcome these hurdles, and how their dietary strategies shift with the changing seasons.

The Challenges of Digesting Plants

A cow ruminating demonstrating the first step in breaking down tough plant matter

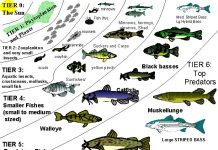

The primary challenge stems from the cellulose content of plant cell walls. Cellulose is a complex carbohydrate that most animals lack the enzymes to break down. This is where the digestive systems of herbivorous animals diverge dramatically from those of carnivores. Carnivores have relatively short digestive tracts, optimized for quickly processing easily digestible protein and fat. Herbivores, however, require extended digestive processes and specialized anatomical features.

Here’s a breakdown of the key challenges:

- Cellulose Digestion: As mentioned, cellulose is the major hurdle. Without the ability to break it down, the nutrients locked within plant cells remain inaccessible.

- Nutrient Density: Plants generally have a lower nutrient density than meat. This means herbivores need to consume a much larger volume of food to obtain the same amount of energy and essential nutrients.

- Toxins and Defenses: Plants aren’t passive food sources. They’ve evolved a variety of chemical defenses – toxins, tannins, and other compounds – to deter herbivores. These compounds can interfere with digestion, reduce nutrient absorption, or even be directly poisonous.

- Silica and Other Abrasives: Many plants contain silica and other abrasive compounds that can wear down teeth.

- Nitrogen Content: Plants generally have lower nitrogen content than animal tissues, making it harder for herbivores to obtain sufficient protein.

To combat these challenges, herbivores have evolved a range of strategies. These include:

- Specialized Teeth: Herbivores typically have broad, flat molars designed for grinding plant material, rather than the sharp teeth of carnivores used for tearing flesh. The shape and arrangement of teeth vary depending on the type of vegetation consumed. For example, grazers like cows have continuously growing molars to compensate for wear and tear.

- Extended Digestive Tracts: A longer digestive tract provides more time for fermentation and nutrient absorption.

- Compartmentalized Stomachs: Ruminants (like cows, sheep, and deer) have a four-chambered stomach. This allows for a multi-stage fermentation process, maximizing nutrient extraction. The first chamber, the rumen, houses a vast community of microorganisms that break down cellulose.

- Cecal Fermentation: Animals like horses and rabbits utilize cecal fermentation. They have a large cecum – a pouch at the junction of the small and large intestines – where microorganisms ferment plant material. However, this process is less efficient than rumination, and some nutrients are lost as waste.

- Coprophagy: Some herbivores, like rabbits and guinea pigs, practice coprophagy – eating their own feces. This allows them to re-ingest nutrients that were not fully absorbed during the first pass through the digestive system, particularly vitamins and minerals produced by gut bacteria.

Symbiotic Relationships: Gut Microbiomes and Herbivory

A vibrant illustration of the diverse microbial community within a herbivores gut

The success of herbivores in digesting plants is inextricably linked to the symbiotic relationships they have with microorganisms in their gut. These microscopic allies – bacteria, archaea, fungi, and protozoa – collectively form the gut microbiome. The microbiome isn’t just present in the herbivore’s gut; it’s essential for its survival.

Here’s how the relationship works:

- Microbial Cellulose Digestion: The most crucial role of the gut microbiome is breaking down cellulose. Herbivores lack the enzymes to do this themselves, but the microorganisms in their gut produce cellulases – enzymes that hydrolyze cellulose into simpler sugars that the herbivore can absorb.

- Vitamin Synthesis: Gut bacteria synthesize essential vitamins, such as B vitamins and vitamin K, which are often lacking in plant material.

- Nutrient Production: Microorganisms produce volatile fatty acids (VFAs) as a byproduct of fermentation. VFAs are a major source of energy for the herbivore.

- Detoxification: Some gut bacteria can detoxify plant toxins, protecting the herbivore from harmful compounds.

- Immune System Development: The gut microbiome plays a vital role in developing and regulating the herbivore’s immune system.

The composition of the gut microbiome varies depending on the herbivore’s diet, age, and environment. Young herbivores acquire their initial microbiome from their mothers, often through coprophagy or licking. The microbiome then evolves over time as the animal consumes different plants and interacts with its environment.

The relationship is mutually beneficial. The herbivore provides the microorganisms with a stable environment, a constant supply of food, and a means of dispersal. In return, the microorganisms provide the herbivore with essential digestive services. This is a classic example of mutualism, a symbiotic relationship where both species benefit. Without this intricate partnership, plant-eating animals simply couldn’t thrive.

The study of the gut microbiome is a rapidly evolving field, and researchers are continually discovering new insights into the complex interactions between herbivores and their microbial partners.

Seasonal Variations in Herbivore Diets

A deer foraging for limited vegetation during the winter months

The availability of plant food varies dramatically throughout the year, forcing herbivores to adapt their dietary strategies to cope with seasonal changes. This is particularly pronounced in temperate and polar regions, where winters can bring harsh conditions and limited vegetation.

Here’s how herbivores respond to seasonal variations:

- Diet Switching: Many herbivores switch to different food sources depending on the season. For example, deer might graze on lush grasses and forbs in the spring and summer, but switch to browsing on twigs, buds, and bark during the winter.

- Migration: Some herbivores, like wildebeest and caribou, undertake long-distance migrations to follow the availability of fresh vegetation. This allows them to access areas with abundant food resources, even during harsh seasons.

- Food Storage: Some herbivores, like squirrels and chipmunks, store food during periods of abundance to help them survive the winter. While not strictly herbivores, they consume seeds and nuts, which are plant-based.

- Fat Storage: Many herbivores build up fat reserves during the summer and fall to provide energy during the winter when food is scarce.

- Reduced Activity: Some herbivores reduce their activity levels during the winter to conserve energy.

- Digestive Adaptations: The gut microbiome can also change seasonally. For example, the abundance of certain microbial species may increase during the winter to help the herbivore digest tougher, more fibrous plant material.

The ability to adapt to seasonal changes is crucial for the survival of herbivores. Those that are unable to find sufficient food during lean times may experience reduced reproductive success, increased mortality rates, or even population declines. Climate change is exacerbating these challenges, as altered weather patterns and shifting vegetation zones disrupt traditional foraging strategies. Understanding how herbivorous animals respond to seasonal variations is essential for effective conservation management. The delicate balance between plant availability and herbivore needs is a cornerstone of ecosystem health.

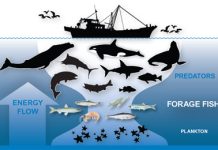

Herbivores and Their Ecosystem Roles

Herbivores, those fascinating plant-eating animals, aren’t simply passive consumers in the grand scheme of nature. They are, in fact, integral architects of their ecosystems, wielding a surprising amount of influence over the landscape and the lives of countless other species. Understanding their roles – as keystone species, shapers of plant communities, and participants in the delicate dance of predator-herbivore interactions – is crucial to appreciating the complexity and interconnectedness of the natural world. It’s easy to think of a deer grazing peacefully, but that simple act ripples outwards, impacting everything from forest regeneration to the survival of apex predators.

Herbivores as Keystone Species

The concept of a keystone species is a cornerstone of ecological understanding. A keystone species is an organism that plays a critical role in maintaining the structure, function, and biodiversity of an ecosystem. Its impact is disproportionately large relative to its abundance. Remove a keystone species, and the ecosystem can undergo dramatic, often cascading, changes. Many herbivores animals fulfill this role, though the specific species and the nature of their influence vary depending on the habitat.

African elephants are a classic example of a keystone herbivore shaping savanna ecosystems

Consider the African elephant. These magnificent creatures aren’t just the largest land animals; they are ecosystem engineers. Their feeding habits – knocking down trees, stripping bark, and creating clearings – prevent woodlands from encroaching on grasslands, maintaining the savanna habitat that supports a vast array of other species. Elephants also disperse seeds over long distances, contributing to plant diversity. Without elephants, savannas would likely transition into closed-canopy forests, drastically altering the landscape and reducing habitat for many animals. The same principle applies, albeit on a smaller scale, to beavers in North American ecosystems. Beavers, though not strictly herbivores (they also consume bark), dramatically alter their environment by building dams, creating wetlands that support a wealth of life.

Another compelling example is the prairie dog in North American grasslands. These small rodents create extensive burrow systems that aerate the soil, improve water infiltration, and provide habitat for other animals. Their grazing also stimulates plant growth and maintains the diversity of grassland vegetation. The decline of prairie dog populations has been linked to declines in grassland bird populations and overall ecosystem health.

Identifying herbivorous animals as keystone species isn’t always straightforward. The role can be subtle and context-dependent. For instance, certain species of deer can influence forest regeneration by selectively browsing on specific tree species, preventing any single species from dominating. This maintains a more diverse forest structure, benefiting a wider range of wildlife. The key takeaway is that herbivores are rarely just consumers; they are active agents of ecological change.

The Impact of Herbivory on Plant Communities

The relationship between herbivores and plants is, of course, fundamental. But it’s far more nuanced than simply “animals eat plants.” Herbivory – the consumption of plants by animals – exerts a powerful selective pressure on plant evolution, driving the development of a remarkable array of defense mechanisms. These defenses, in turn, influence the distribution, abundance, and diversity of plant species.

Giraffes have evolved to browse on acacia trees but the trees have also evolved defenses like thorns

Plants have evolved both physical and chemical defenses against herbivores. Physical defenses include thorns, spines, tough leaves, and thick bark. Chemical defenses involve the production of toxins, repellents, and digestibility-reducing compounds. For example, milkweed plants produce cardiac glycosides, toxic compounds that deter many herbivores, but monarch butterflies have evolved the ability to sequester these toxins, making themselves poisonous to predators. This co-evolutionary arms race between plants and herbivores is a driving force behind plant diversity.

Herbivory also influences plant community structure. Selective grazing can favor certain plant species over others, leading to shifts in vegetation composition. For example, overgrazing by livestock or wild herbivores can lead to the dominance of unpalatable or invasive plant species, reducing biodiversity. Conversely, moderate grazing can promote plant diversity by preventing any single species from becoming dominant.

The impact of herbivores on plant communities extends beyond direct consumption. Herbivores can also influence plant dispersal patterns. Animals that eat fruits and seeds often disperse those seeds over long distances, contributing to plant colonization and gene flow. This is particularly important for plants with large seeds or limited dispersal mechanisms. Furthermore, the physical disturbance created by herbivores – trampling, digging, and wallowing – can create opportunities for new plant growth and increase habitat heterogeneity.

Understanding these complex interactions is crucial for effective conservation management. For example, restoring native herbivore populations can be a valuable tool for managing vegetation and promoting biodiversity in degraded ecosystems.

Predator-Herbivore Interactions: A Delicate Balance

The relationship between herbivores and their predators is a classic example of a trophic interaction – the feeding relationships between organisms in an ecosystem. This interaction is not simply a matter of predator chasing prey; it’s a complex interplay of adaptations, behaviors, and ecological factors that shapes the dynamics of both populations.

The predatorprey relationship between lions and zebras is a key driver of ecosystem dynamics

Predation exerts a strong selective pressure on herbivores, favoring traits that enhance their ability to avoid being eaten. These traits include speed, agility, camouflage, vigilance, and defensive behaviors such as herding or alarm calls. Herbivores also evolve physiological adaptations, such as increased reproductive rates, to compensate for predation losses.

Conversely, predation drives the evolution of hunting strategies and physical adaptations in predators. Lions, for example, have evolved powerful muscles, sharp claws, and coordinated hunting behaviors to effectively prey on large herbivores like zebras and wildebeest.

The presence of predators can also have indirect effects on herbivore behavior and distribution. The “landscape of fear” – the spatial distribution of risk imposed by predators – can influence where herbivores forage, rest, and reproduce. Herbivores may avoid areas with high predator density, even if those areas offer abundant food resources. This can lead to changes in vegetation patterns and ecosystem structure.

The removal of predators can have cascading effects on herbivore populations and plant communities. For example, the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s led to a dramatic decline in elk populations, which had been overgrazing riparian vegetation. The recovery of riparian vegetation, in turn, benefited a wide range of other species, including beavers, fish, and birds. This example illustrates the importance of maintaining intact predator-prey relationships for ecosystem health.

The balance between predators and herbivores is often a delicate one, influenced by factors such as habitat availability, prey density, and climate change. Human activities, such as hunting and habitat destruction, can disrupt this balance, leading to ecological consequences. Effective conservation management requires a holistic understanding of these complex interactions and a commitment to maintaining the integrity of trophic webs. The health of herbivores animals is inextricably linked to the health of their ecosystems, and their role as both consumers and prey is vital for maintaining the biodiversity and resilience of our planet.

Conservation Status and Threats to Herbivores

The fate of herbivores animals is inextricably linked to the health of our planet. These gentle giants and unassuming grazers are facing unprecedented challenges in the modern world, pushing many species towards the brink of extinction. Understanding the threats they face – habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching and illegal hunting, and the increasingly devastating effects of climate change – is crucial for implementing effective conservation strategies. It’s a sobering reality that the very ecosystems these animals help maintain are now actively working against their survival.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

Perhaps the most pervasive threat to herbivorous animals globally is the relentless destruction and alteration of their natural habitats. This isn’t simply about shrinking landmasses; it’s about the fragmentation of ecosystems, creating isolated pockets of habitat that are too small and disconnected to support viable populations. The primary driver of this loss is human activity, specifically:

- Agricultural Expansion: The demand for agricultural land – for crops and livestock – is a major force behind deforestation and the conversion of grasslands. Vast areas of land are cleared to make way for farms, displacing herbivores and disrupting their migratory routes. Consider the African savanna, where expanding farmland is encroaching on the traditional grazing grounds of wildebeest, zebras, and gazelles.

- Urbanization and Infrastructure Development: As human populations grow, so too does the need for cities, roads, and other infrastructure. This development often occurs at the expense of natural habitats, fragmenting ecosystems and creating barriers to movement for animals that eat plants. A new highway, for example, can effectively divide a forest, preventing herbivores from accessing vital resources on the other side.

- Logging and Mining: The extraction of timber and minerals can have devastating impacts on herbivore habitats. Logging operations remove trees, destroying food sources and shelter, while mining activities can contaminate soil and water, rendering areas uninhabitable.

- Wetland Drainage: Wetlands are incredibly important ecosystems, providing habitat for a wide range of herbivores, from manatees to musk deer. However, wetlands are often drained for agricultural use or urban development, leading to significant habitat loss.

The consequences of habitat fragmentation are far-reaching. Isolated populations are more vulnerable to inbreeding, genetic drift, and local extinction. They also become more susceptible to edge effects – changes in environmental conditions at the boundaries of fragmented habitats – which can negatively impact herbivore health and reproduction. Furthermore, fragmentation limits the ability of herbivores to respond to environmental changes, such as shifts in climate or the outbreak of disease. A classic example is the Florida panther, whose fragmented habitat severely limited its genetic diversity and nearly drove it to extinction. Conservation efforts focused on creating wildlife corridors – connecting fragmented habitats – have been crucial to its recovery.

Poaching and Illegal Hunting

A heartbreaking image of a poached rhinoceros highlighting the devastating impact of illegal hunting

While habitat loss is a slow, insidious threat, poaching and illegal hunting represent a more immediate and direct danger to many herbivore species. Driven by the demand for animal products – horns, ivory, meat, and skins – poaching continues to decimate populations of iconic herbivores around the world.

- Rhinoceroses: Perhaps the most well-known example is the plight of rhinoceroses, relentlessly targeted for their horns, which are falsely believed to have medicinal properties in some cultures. Despite international efforts to combat poaching, rhino populations continue to decline, with some subspecies on the verge of extinction.

- Elephants: Elephants are poached for their ivory tusks, which are used to create ornaments and carvings. The illegal ivory trade fuels a brutal cycle of violence, with thousands of elephants killed each year.

- Antelopes and Deer: Many species of antelopes and deer are hunted for their meat (bushmeat) and skins. This is particularly prevalent in Africa and Asia, where poverty and lack of law enforcement contribute to the problem.

- Illegal Trade in Traditional Medicine: Certain herbivores are targeted for body parts used in traditional medicine, even if those parts have no proven medicinal value.

The impact of poaching extends beyond the immediate loss of individual animals. It disrupts social structures, reduces genetic diversity, and can lead to the decline of entire populations. Moreover, poaching often occurs in conjunction with other illegal activities, such as logging and wildlife trafficking, exacerbating the threats to herbivore habitats. Anti-poaching efforts are often hampered by limited resources, corruption, and the vastness of the areas that need to be protected. Innovative technologies, such as drones and camera traps, are being used to monitor herbivore populations and detect poaching activity, but more needs to be done to address the underlying drivers of demand and improve law enforcement.

Climate Change and its Effects on Plant Availability

A parched African savanna during a severe drought illustrating the impact of climate change on plant availability

Climate change is rapidly emerging as a major threat to herbivores, not directly through hunting or habitat destruction, but through its profound impact on plant availability and ecosystem dynamics. Herbivores animals are fundamentally dependent on plants for their survival, and any disruption to plant communities can have cascading effects throughout the food chain.

- Changes in Precipitation Patterns: Altered rainfall patterns – including more frequent and severe droughts and floods – can significantly impact plant growth and distribution. Droughts can lead to widespread vegetation die-off, leaving herbivores with limited food resources. Floods can inundate grazing lands and damage plant roots, reducing their ability to recover.

- Increased Temperatures: Rising temperatures can stress plants, reducing their productivity and making them more susceptible to pests and diseases. This can lead to a decline in the quality and quantity of forage available to herbivores.

- Shifts in Plant Communities: As climate changes, plant communities are shifting, with some species expanding their ranges and others contracting. Herbivores may struggle to adapt to these changes, particularly if they are specialized feeders. For example, the koala, which relies almost exclusively on eucalyptus leaves, is facing a crisis as climate change alters the distribution and nutritional content of eucalyptus forests.

- Increased Frequency of Extreme Weather Events: More frequent and intense heatwaves, wildfires, and storms can devastate plant communities, leaving herbivores vulnerable to starvation and displacement.

- Ocean Acidification and Seagrass Beds: For marine herbivores like dugongs and manatees, ocean acidification threatens the seagrass beds they rely on for food. Acidification weakens seagrass, making it less resilient to environmental stressors.

The effects of climate change are not uniform across all regions. Some areas are experiencing more rapid warming and more dramatic changes in precipitation patterns than others. Herbivores in these areas are particularly vulnerable. Furthermore, climate change is often interacting with other threats, such as habitat loss and poaching, creating a synergistic effect that amplifies the risks to herbivore populations. Mitigating climate change through reducing greenhouse gas emissions is essential for protecting herbivores and the ecosystems they inhabit. Adaptation strategies, such as restoring degraded habitats and creating climate refugia, can also help herbivores cope with the changing climate.

The future of herbivores animals hangs in the balance. Addressing these interconnected threats requires a multifaceted approach, encompassing habitat conservation, anti-poaching efforts, climate change mitigation, and sustainable land management practices. It demands international cooperation, community involvement, and a fundamental shift in our relationship with the natural world. The survival of these magnificent creatures is not just a matter of ecological concern; it is a reflection of our own commitment to preserving the planet for future generations.

Fascinating Facts and Unique Herbivores

This section delves into the captivating world of some truly remarkable herbivores animals, creatures that have evolved unique adaptations to thrive on plant-based diets. We’ll explore the Okapi, often called the “forest giraffe,” the gentle and serene Manatee, and the iconic Koala, a specialist in eucalyptus consumption. These animals aren’t just examples of plant-eating animals; they represent fascinating evolutionary stories and highlight the incredible diversity within the herbivore world.

The Okapi: A Forest Giraffe

An Okapi often referred to as the forest giraffe blends seamlessly into its rainforest habitat

The Okapi (Okapia johnstoni) is a truly enigmatic creature. Often described as a cross between a giraffe and a zebra, this animal is actually the giraffe’s only close living relative. Found exclusively in the dense rainforests of the Democratic Republic of Congo in Central Africa, the Okapi presents a striking example of adaptation to a very specific environment. Unlike its savanna-dwelling cousin, the giraffe, the Okapi has a much shorter neck, allowing it to navigate the undergrowth with ease. Its reddish-brown coat, coupled with striking zebra-like stripes on its legs, provides excellent camouflage in the dappled sunlight of the rainforest floor.

Physical Characteristics and Adaptations:

- Size and Weight: Okapis typically stand around 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall at the shoulder and weigh between 440 and 770 pounds (200-350 kilograms).

- Tongue: Perhaps one of the Okapi’s most remarkable features is its incredibly long, prehensile tongue, which can measure up to 18 inches (45 centimeters) in length. This tongue is used to strip leaves from branches, groom themselves, and even clean their ears!

- Ossicones: Like giraffes, Okapis possess ossicones – bony, skin-covered horns. However, in Okapis, these are smaller and present in both males and females.

- Large Ears: Their large, mobile ears help them detect predators and communicate with each other in the dense forest.

Diet and Feeding Behavior:

Okapis are primarily folivores, meaning their diet consists mainly of leaves. They are incredibly selective feeders, consuming leaves from over 100 different plant species. They favor young shoots and buds, which are more nutritious and easier to digest. They also supplement their diet with fruits, fungi, and clay, which provides essential minerals. The Okapi’s digestive system, while not as complex as some other herbivorous animals, is still adapted for breaking down plant matter. They have a multi-chambered stomach that aids in fermentation, allowing them to extract more nutrients from their food.

Conservation Status and Threats:

Sadly, the Okapi is classified as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Their population is estimated to be less than 50,000 individuals, and it is declining. The primary threats to Okapis include:

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation due to logging, agriculture, and human settlement is destroying their rainforest habitat.

- Poaching: Okapis are hunted for their meat and skin.

- Political Instability: The ongoing political instability in the Democratic Republic of Congo hinders conservation efforts.

Conservation organizations are working to protect Okapis through habitat preservation, anti-poaching patrols, and community education programs. The future of this “forest giraffe” depends on continued conservation efforts.

The Manatee: Gentle Giants of the Water

A West Indian Manatee gracefully swimming in its natural habitat showcasing its gentle nature

The Manatee (genus Trichechus) is a large, fully aquatic mammal, often referred to as a “sea cow” due to its gentle nature and herbivorous diet. There are three recognized species of Manatee: the West Indian Manatee, the Amazonian Manatee, and the African Manatee. These magnificent creatures inhabit warm, shallow coastal waters and rivers. They are a prime example of how herbivores animals can adapt to a completely aquatic lifestyle.

Physical Characteristics and Adaptations:

- Size and Weight: Manatees can grow up to 13 feet (4 meters) long and weigh over 1,300 pounds (600 kilograms).

- Body Shape: They have a streamlined, torpedo-shaped body, perfectly adapted for swimming.

- Paddle-like Flippers: Their forelimbs have evolved into paddle-like flippers, used for steering and maneuvering in the water.

- Flat Tail: Their broad, flat tail provides propulsion.

- Slow Metabolism: Manatees have a very slow metabolism, which allows them to survive on a relatively low-energy diet.

Diet and Feeding Behavior:

Manatees are obligate herbivores, meaning their diet consists entirely of plants. They are voracious eaters, consuming up to 10-15% of their body weight in vegetation every day. Their primary food source is aquatic plants, such as seagrasses, water hyacinth, and algae. They use their flexible lips to grasp and pull plants into their mouths. Manatees lack incisors and canines, relying on their ridged, plate-like molars to grind up plant matter. Their digestive system is exceptionally long – up to 130 feet (40 meters) – to maximize nutrient absorption from the fibrous plants they consume.

Conservation Status and Threats:

Manatees face numerous threats, leading to their classification as Vulnerable or Endangered, depending on the species. These threats include:

- Boat Strikes: Collisions with boats are a major cause of Manatee mortality.

- Habitat Loss: Degradation of seagrass beds due to pollution, dredging, and coastal development reduces their food supply.

- Entanglement in Fishing Gear: Manatees can become entangled in fishing lines and nets.

- Red Tide: Harmful algal blooms (red tides) can produce toxins that are lethal to Manatees.

Conservation efforts include boat speed restrictions in Manatee habitats, seagrass restoration projects, and rescue and rehabilitation programs for injured Manatees.

Koalas: Eucalyptus Specialists

The Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) is an iconic Australian marsupial, renowned for its adorable appearance and highly specialized diet. Koalas are perhaps the most well-known example of a herbivore with an extremely restricted diet – they almost exclusively eat eucalyptus leaves. This specialization has shaped their evolution and behavior in remarkable ways. They are a fascinating example of how animals that eat plants can become incredibly adapted to a single food source.

Physical Characteristics and Adaptations:

- Size and Weight: Koalas typically weigh between 9 and 33 pounds (4-15 kilograms) and measure 24-33 inches (60-85 centimeters) in length.

- Fur: Their thick, woolly fur provides insulation and protection from the elements.

- Strong Claws: They have strong claws that allow them to climb trees with ease.

- Opposable Thumbs: Koalas have two opposable thumbs on their front paws, providing a secure grip on branches.

Diet and Feeding Behavior:

Eucalyptus leaves are notoriously low in nutrients and high in toxins. Koalas have evolved several adaptations to cope with this challenging diet:

- Specialized Digestive System: They possess a long caecum, a pouch at the beginning of the large intestine, which contains bacteria that help break down the tough cellulose in eucalyptus leaves and detoxify the harmful compounds.

- Slow Metabolism: Like Manatees, Koalas have a very slow metabolism, conserving energy and allowing them to process the low-nutrient eucalyptus leaves.

- Selective Feeding: They are highly selective feeders, choosing leaves from specific eucalyptus species that are less toxic and more nutritious.

- Sleep: Koalas spend up to 20 hours a day sleeping, conserving energy.

Conservation Status and Threats:

Koalas are listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Their populations are declining due to:

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation and land clearing for agriculture and urban development are destroying their eucalyptus forest habitat.

- Bushfires: Severe bushfires, such as those experienced in Australia in 2019-2020, have devastated Koala populations.

- Disease: Chlamydia is a common disease that affects Koalas, causing blindness, infertility, and death.

- Climate Change: Climate change is exacerbating the threats of bushfires and habitat loss.

Conservation efforts include habitat restoration, disease management programs, and community education initiatives. Protecting the eucalyptus forests is crucial for the survival of these beloved herbivorous animals. Understanding the unique challenges faced by these examples of herbivores is vital for ensuring their continued existence.

The Future of Herbivores: Coexistence and Conservation Efforts

The future of herbivores animals is inextricably linked to the health of our planet and the choices we make today. While these plant-eating animals have thrived for millennia, adapting to diverse environments and playing crucial roles in ecosystem function, they now face unprecedented challenges. Understanding these threats and implementing effective conservation strategies is paramount to ensuring their survival for generations to come. This section will delve into the complexities of coexistence, exploring current conservation efforts, innovative approaches, and the vital role individuals can play in safeguarding these magnificent creatures.

Understanding the Interconnectedness of Herbivore Conservation

Conservation isn’t simply about protecting individual species; it’s about recognizing the intricate web of life and addressing the root causes of decline. For herbivorous animals, this means acknowledging their dependence on healthy plant communities, functional ecosystems, and the absence of excessive human interference. A holistic approach is essential, one that considers habitat preservation, anti-poaching measures, climate change mitigation, and community engagement.

Habitat Preservation and Restoration: The Cornerstone of Herbivore Survival

The most significant threat to herbivores globally is habitat loss and fragmentation. As human populations expand, natural landscapes are converted into agricultural land, urban areas, and infrastructure projects. This not only reduces the available space for herbivores to roam and forage but also isolates populations, limiting genetic diversity and increasing vulnerability to disease and local extinction.

- Protected Areas: Establishing and effectively managing protected areas – national parks, wildlife reserves, and conservancies – is a critical first step. These areas provide safe havens for herbivores, allowing them to breed, feed, and migrate without the constant threat of human encroachment. However, simply designating protected areas isn’t enough. They require adequate funding, skilled personnel, and robust enforcement to prevent illegal activities like poaching and logging.

- Habitat Corridors: Fragmentation can be mitigated by creating habitat corridors – strips of land that connect isolated populations, allowing for gene flow and facilitating movement in response to changing environmental conditions. These corridors can take various forms, from forested strips along rivers to underpasses beneath highways.

- Restoration Ecology: In areas where habitat has already been degraded, restoration ecology offers a promising path forward. This involves actively restoring degraded ecosystems to their former glory, replanting native vegetation, removing invasive species, and reintroducing herbivores where appropriate. For example, reforestation efforts in the Amazon rainforest are crucial for restoring habitat for tapirs and other herbivorous mammals.

- Sustainable Land Management: Promoting sustainable land management practices outside of protected areas is equally important. This includes encouraging responsible agriculture, forestry, and grazing practices that minimize environmental impact and allow for coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Combating Poaching and Illegal Hunting: Protecting Vulnerable Populations

Poaching and illegal hunting pose a direct threat to many herbivore species, particularly those with valuable body parts like rhinoceroses and elephants. The demand for rhino horn and ivory fuels a lucrative black market, driving these animals towards extinction.

- Anti-Poaching Patrols: Deploying well-trained and equipped anti-poaching patrols is essential for deterring poachers and apprehending those involved in illegal wildlife trade. These patrols often rely on advanced technologies like drones, camera traps, and GPS tracking to monitor wildlife populations and detect poaching activity.

- Community-Based Conservation: Engaging local communities in conservation efforts is crucial for long-term success. Providing economic incentives for communities to protect wildlife, such as ecotourism opportunities and revenue sharing from conservation fees, can foster a sense of ownership and encourage active participation in anti-poaching efforts.

- Demand Reduction: Addressing the demand for illegal wildlife products is equally important. This requires raising awareness among consumers, strengthening law enforcement efforts to disrupt trafficking networks, and working with governments to implement stricter penalties for wildlife crimes.

- Dehorning Programs: In the case of rhinoceroses, dehorning programs – removing the rhino’s horn to deter poachers – have shown some success, although they are controversial and require ongoing maintenance.

A rhinoceros undergoing a dehorning procedure as a conservation measure against poaching

Mitigating the Impacts of Climate Change: Adapting to a Changing World

Climate change is exacerbating the threats faced by herbivores, altering plant communities, disrupting migration patterns, and increasing the frequency of extreme weather events like droughts and floods.

- Climate-Resilient Habitats: Identifying and protecting climate-resilient habitats – areas that are less vulnerable to the impacts of climate change – is crucial. These areas may include high-elevation refugia, areas with abundant water resources, or regions with diverse plant communities.

- Assisted Migration: In some cases, assisted migration – intentionally relocating herbivores to more suitable habitats – may be necessary to help them adapt to changing climate conditions. However, this is a controversial strategy that requires careful planning and consideration of potential ecological impacts.

- Water Resource Management: Ensuring access to adequate water resources is particularly important for herbivores in arid and semi-arid regions. This may involve developing water harvesting techniques, restoring degraded watersheds, and managing water resources sustainably.

- Monitoring and Research: Continuous monitoring and research are essential for understanding how climate change is affecting herbivore populations and developing effective adaptation strategies. This includes tracking changes in plant phenology, monitoring herbivore movements, and assessing the impacts of extreme weather events.

The Role of Gut Microbiomes in Herbivore Adaptation and Conservation

Recent research highlights the critical role of gut microbiomes in the ability of herbivores to digest plants and adapt to changing diets. The complex community of microorganisms living in an herbivore’s digestive system helps break down cellulose and other plant fibers, extracting essential nutrients.

- Microbiome Research: Further research into the composition and function of herbivore gut microbiomes is crucial for understanding their adaptive capacity and identifying potential conservation strategies.

- Probiotic Supplementation: In some cases, probiotic supplementation – introducing beneficial microorganisms into the gut – may help herbivores cope with dietary changes or recover from stress.

- Habitat Quality and Microbiome Diversity: Maintaining habitat quality and plant diversity is essential for supporting a healthy and diverse gut microbiome in herbivores.

Community Engagement and Education: Fostering a Culture of Conservation

Ultimately, the future of herbivores depends on fostering a culture of conservation that values biodiversity and recognizes the importance of coexistence.

- Education Programs: Implementing education programs in local communities can raise awareness about the ecological importance of herbivores and the threats they face.

- Ecotourism: Promoting ecotourism opportunities can generate economic benefits for local communities while also providing incentives for wildlife conservation.

- Citizen Science: Engaging citizens in citizen science projects – collecting data on herbivore populations, monitoring habitat conditions, and reporting poaching activity – can empower individuals to contribute to conservation efforts.

- Policy Advocacy: Supporting policies that promote habitat preservation, combat poaching, and mitigate climate change is essential for creating a more sustainable future for herbivores.

A Global Effort: Collaboration and Innovation

Conserving herbivores animals requires a global effort, involving collaboration between governments, conservation organizations, researchers, and local communities. Innovation is also key, exploring new technologies and approaches to address the challenges facing these magnificent creatures. From advanced monitoring systems to innovative anti-poaching strategies, the future of herbivore conservation lies in our collective commitment to protecting these vital components of our planet’s biodiversity. The time to act is now, to ensure that future generations can marvel at the grace of a giraffe, the power of an elephant, and the delicate beauty of all herbivorous animals that share our world.

WildWhiskers is a dedicated news platform for animal lovers around the world. From heartwarming stories about pets to the wild journeys of animals in nature, we bring you fun, thoughtful, and adorable content every day. With the slogan “Tiny Tails, Big Stories!”, WildWhiskers is more than just a news site — it’s a community for animal enthusiasts, a place to discover, learn, and share your love for the animal kingdom. Join WildWhiskers and open your heart to the small but magical lives of animals around us!