Have you ever gazed upon a dinosaur skeleton in a museum and wondered, truly wondered, what cataclysmic events led to the disappearance of these magnificent prehistoric animals? For centuries, the story was relatively simple: a giant asteroid, a fiery impact, and… extinction. But the truth, as science so often reveals, is far more nuanced, and frankly, a lot more fascinating.

We’ve all heard about the asteroid, the one that slammed into the Yucatan Peninsula around 66 million years ago. But increasingly, scientists are realizing that it wasn’t a single, clean break. The demise of the dinosaurs – and countless other species – was likely a complex interplay of factors, a perfect storm of geological and environmental upheaval. This isn’t just about rewriting history books; it’s about understanding the fragility of life on Earth, and perhaps, even predicting our own future.

In this blog post, we’re diving deep into the latest theories surrounding the extinction events that have punctuated our planet’s history. We’ll explore the evidence for the Chicxulub impact and its immediate aftermath, but we won’t stop there. We’ll unravel the role of massive volcanic eruptions from the Deccan Traps, investigate the impact of dramatic climate change – including a prehistoric warming event eerily similar to our own – and even consider the possibility that disease and biological factors played a more significant role than previously thought.

Prepare to rethink everything you thought you knew about extinction. It wasn’t always sudden, and it wasn’t always about a single, dramatic event. We’ll also look at the concept of “background extinction” and ask a sobering question: are we currently living through a sixth mass extinction, driven by our own actions? Join us as we uncover the secrets of the past, and learn what these ancient disappearances can teach us about the future of prehistoric animals and all life on Earth.

The Classic Culprit: Asteroid Impact and the Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction

For decades, the story of the dinosaurs’ demise – and the extinction of so many other prehistoric animals – was largely framed around a single, dramatic event: a colossal asteroid impact. It’s a narrative that captures the imagination, a cosmic bullet ending an era. But like most historical mysteries, the truth is far more nuanced than a simple cause-and-effect relationship. The impact wasn’t just the reason, but a trigger, a catastrophic punctuation mark at the end of a period of increasing environmental stress. Let’s delve into the evidence, the immediate aftermath, the long-term consequences, and finally, why some creatures managed to weather the storm while others vanished forever. It’s a story of destruction, resilience, and a little bit of luck.

The Chicxulub Impact: Evidence and Immediate Effects

The story begins, quite literally, with a crater. In the early 1980s, physicist Luis Alvarez and his geologist son, Walter Alvarez, were searching for evidence of extinction events in geological layers. They stumbled upon an unusually high concentration of iridium, a rare element on Earth but common in asteroids, at the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods – the K-Pg boundary, formerly known as the K-T boundary. This layer, a thin band of sediment found globally, was a geological fingerprint of something extraordinary.

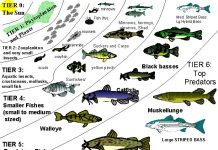

Map showing the location and estimated size of the Chicxulub impact crater in the Yucatan Peninsula

The iridium wasn’t the only clue. Shocked quartz, tektites (small glassy spheres formed from melted rock ejected during an impact), and soot layers were also found in abundance at the K-Pg boundary. These findings pointed to a single, terrifying conclusion: a massive object from space had collided with Earth. Further investigation, utilizing gravity anomalies and seismic surveys, eventually revealed the culprit – the Chicxulub crater, buried beneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico.

The scale of the impact is almost incomprehensible. The asteroid, estimated to be around 10-15 kilometers (6-9 miles) in diameter, slammed into Earth at a speed of roughly 20 kilometers per second (45,000 mph). The energy released was equivalent to billions of atomic bombs. Imagine the instantaneous devastation. The impact itself would have vaporized everything within a radius of hundreds of kilometers. A superheated plume of rock and debris was ejected into the atmosphere, spreading across the globe.

The immediate effects were apocalyptic. Mega-tsunamis, hundreds of meters high, radiated outwards from the impact site, scouring coastlines and inundating vast areas of land. Wildfires ignited across continents, fueled by the heat and the ejected debris raining back down. The atmosphere was filled with dust, soot, and sulfur aerosols, blocking out sunlight. This wasn’t a gradual darkening; it was an almost instantaneous plunge into darkness.

It’s easy to get lost in the numbers and the scientific jargon, but it’s crucial to visualize the sheer horror of that moment. Imagine being a prehistoric animal – a majestic Tyrannosaurus rex, a graceful Triceratops, a soaring Pteranodon – and witnessing the sky fall. The ground shaking, the air burning, the sun disappearing. It was a world ending in real-time. The initial blast and its immediate consequences likely wiped out a significant portion of life within hours or days.

Beyond the Impact: Long-Term Environmental Consequences

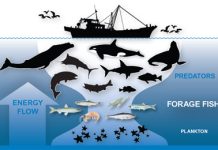

The initial shockwave was devastating, but the long-term environmental consequences were arguably even more profound. The dust and aerosols injected into the atmosphere created a global “impact winter” that lasted for years, perhaps even decades. Sunlight was blocked, causing a dramatic drop in temperatures. Photosynthesis ground to a halt, collapsing the base of the food chain.

Illustration depicting the impact winter scenario following the Chicxulub impact showing a darkened Earth covered in dust and debris

This wasn’t just a simple cooling event. The impact also released massive amounts of sulfur from the gypsum-rich rocks of the Yucatán Peninsula. Sulfur dioxide reacts with water in the atmosphere to form sulfuric acid aerosols, which are incredibly effective at reflecting sunlight. This further exacerbated the cooling effect and also led to acid rain, which acidified oceans and soils, harming plant and animal life.

The disruption to the carbon cycle was immense. With photosynthesis suppressed, carbon dioxide levels initially dropped. However, the wildfires released vast amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, creating a complex and fluctuating climate system. The oceans, already stressed by acidification, experienced widespread anoxia (oxygen depletion) as decaying organic matter consumed what little oxygen remained.

The combination of darkness, cold, acid rain, and anoxia created a truly hostile environment. Plants died off, herbivores starved, and carnivores followed suit. The food web unraveled, leading to a cascade of extinctions. It wasn’t just the large, iconic dinosaurs that perished. Marine reptiles, ammonites, many species of birds, and countless invertebrates also disappeared. The K-Pg extinction event was one of the most severe in Earth’s history, wiping out an estimated 76% of plant and animal species.

The recovery was slow and arduous. It took millions of years for ecosystems to rebuild and diversify. The world that emerged after the K-Pg extinction was fundamentally different from the world that had existed before. The age of the dinosaurs was over, and the age of mammals had begun.

Who Survived and Why? Examining Resilience in the Face of Catastrophe

Amidst the widespread devastation, some creatures managed to survive. Understanding why they survived is crucial for understanding the dynamics of extinction and the factors that contribute to resilience. It wasn’t simply a matter of being “stronger” or “better” adapted. Luck, lifestyle, and sheer happenstance played significant roles.

Smaller animals, particularly those that could burrow or find shelter, had a higher chance of survival. Mammals, for example, were generally small and adaptable during the Cretaceous period. They were able to find refuge in burrows, feed on insects and seeds, and survive on limited resources. Birds, too, benefited from their ability to fly and potentially find pockets of habitable environments.

Illustration depicting small mammals surviving the KPg extinction event by sheltering in burrows and scavenging for food

Aquatic ecosystems, while severely impacted, offered some degree of refuge. Organisms living in deeper waters were less affected by the initial impact and the subsequent wildfires. Freshwater environments, buffered from the worst effects of ocean acidification, also provided havens for some species.

Diet also played a crucial role. Animals that were generalists – those that could eat a variety of foods – were more likely to survive than specialists, which relied on specific food sources that may have become scarce. Detritivores, organisms that feed on dead organic matter, also had an advantage, as there was plenty of decaying material available in the aftermath of the extinction.

Perhaps the most important factor was seed banking. Plants that produced seeds capable of remaining dormant for extended periods had a higher chance of recolonizing areas after the impact winter subsided. Similarly, animals with resilient eggs or spores were more likely to survive.

The survival of certain species wasn’t necessarily a testament to their inherent superiority, but rather a combination of fortunate circumstances. It highlights the role of chance in evolutionary history and the importance of adaptability in the face of catastrophic events. The story of the K-Pg extinction isn’t just a story of loss; it’s also a story of survival, resilience, and the enduring power of life to find a way, even in the darkest of times. The prehistoric animals that persevered laid the foundation for the world we know today, a world shaped by the echoes of that ancient impact.

Volcanic Fury: The Role of Deccan Traps

The asteroid impact at Chicxulub often steals the spotlight when discussing the extinction of the prehistoric animals at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary. But what if the story isn’t quite so simple? What if another, slower, more insidious force was at play, perhaps even amplifying the devastation caused by the impact? Enter the Deccan Traps, a massive volcanic province in what is now India, and a growing body of evidence suggests its eruptions played a far more significant role in the extinction event than previously thought. It’s a fascinating, and frankly, terrifying thought – that the Earth itself was actively contributing to the demise of so many species.

Unraveling the Deccan Traps: Timing and Scale of Eruptions

A dramatic view of the basalt columns forming part of the Deccan Traps in India

The Deccan Traps aren’t a single volcano, but a vast flood basalt province. Imagine a region the size of France, covered in layer upon layer of solidified lava, sometimes reaching thicknesses of over 2 kilometers (1.2 miles). This wasn’t a single, explosive event, but a series of eruptions spanning hundreds of thousands of years, possibly even a million years, around the K-Pg boundary. The sheer scale is almost incomprehensible. We’re talking about an estimated 1.5 million cubic kilometers of lava – enough to cover the entire United States under half a mile of basalt!

Determining the precise timing of these eruptions has been a major challenge for scientists. Early dating methods suggested the bulk of the eruptions occurred before the Chicxulub impact, seemingly exonerating the Deccan Traps from a primary role in the extinction. However, more recent, high-precision dating techniques, utilizing argon-argon geochronology and other methods, have revealed a more complex picture. It now appears that the most intense phase of eruptions coincided remarkably closely with the K-Pg boundary, and continued for a significant period after the impact. This temporal overlap is crucial.

The eruptions weren’t uniform either. There were pulses of intense activity interspersed with periods of relative quiescence. The initial phase, beginning around 66.2 million years ago, saw massive outpourings of lava, creating the bulk of the basalt flows. A second, more prolonged phase followed, characterized by smaller, but still significant, eruptions and the formation of volcanic ash clouds. Understanding these phases is vital to understanding the environmental consequences. The type of lava also matters. The Deccan Traps primarily erupted basalt, a relatively fluid lava that spread over vast distances, rather than building up into steep-sided cones. This meant the eruptions were less explosive in the traditional sense, but the sheer volume of lava released had profound effects. It’s a subtle but important distinction – a slow, relentless assault on the atmosphere, rather than a single, cataclysmic blast.

Volcanic Gases and Climate Change: A Slow Burn Extinction?

The lava itself wasn’t the primary killer. It was the gases released during the eruptions – particularly sulfur dioxide (SO2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) – that wreaked havoc on the global climate. Sulfur dioxide, when injected into the stratosphere, reacts with water vapor to form sulfuric acid aerosols. These aerosols reflect incoming sunlight back into space, leading to a period of global cooling. Imagine a persistent, planet-wide haze, dimming the sun and disrupting photosynthesis. This cooling effect could have been devastating for prehistoric animals reliant on sunlight for warmth or for the plants they consumed.

However, the story doesn’t end there. While sulfur dioxide causes short-term cooling, carbon dioxide is a long-lived greenhouse gas. As the Deccan Traps continued to erupt, massive amounts of CO2 were released into the atmosphere, gradually warming the planet. This is where things get really complicated. The initial cooling from sulfur dioxide may have stressed ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to the subsequent warming caused by carbon dioxide. It’s a one-two punch, a climate whiplash that many species simply couldn’t withstand.

The amount of CO2 released by the Deccan Traps is estimated to be enormous – potentially comparable to, or even exceeding, the amount released by the Chicxulub impact. Some studies suggest that the volcanic CO2 emissions alone could have caused a significant warming trend, even without the impact. This warming would have led to ocean acidification, disrupting marine ecosystems and further exacerbating the extinction crisis. The oceans absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, but this process lowers the pH of the water, making it more acidic. This acidity makes it difficult for marine organisms, like shellfish and corals, to build and maintain their shells and skeletons.

Furthermore, the Deccan Traps eruptions released other gases, such as fluorine and chlorine, which could have contributed to acid rain and further damaged ecosystems. It’s a complex cocktail of atmospheric pollutants, all working in concert to destabilize the planet. The sheer persistence of these volcanic emissions, lasting for hundreds of thousands of years, is what sets them apart from the immediate, but relatively short-lived, effects of the impact.

Synergistic Effects: Impact and Volcanism Working Together

An artistic rendering illustrating the simultaneous occurrence of an asteroid impact and volcanic eruptions suggesting a synergistic relationship

The emerging consensus among many scientists is that the Chicxulub impact and the Deccan Traps eruptions weren’t independent events, but rather a deadly synergy. The impact may have even triggered or intensified the Deccan Traps volcanism. The idea is that the shockwaves from the impact traveled through the Earth, reaching the mantle plume beneath India and causing it to erupt more vigorously. This is still a hotly debated topic, but there’s growing evidence to support it.

One line of evidence comes from the timing of the most intense phase of Deccan Traps eruptions, which appears to have begun shortly after the impact. Another comes from studies of the lava flows themselves, which show evidence of increased eruption rates and changes in magma composition following the impact. It’s as if the impact gave the Earth a “kick,” unleashing a torrent of volcanic fury.

Even if the impact didn’t directly trigger the eruptions, it undoubtedly exacerbated their effects. The impact created a global dust cloud that blocked sunlight, disrupting photosynthesis and causing a temporary cooling period. This cooling may have weakened ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to the long-term warming caused by the Deccan Traps. The impact also released massive amounts of dust and debris into the atmosphere, which could have interacted with the volcanic gases, further altering the climate.

Think of it like a patient already weakened by a serious illness (the Deccan Traps volcanism) being struck by a sudden, traumatic injury (the Chicxulub impact). The combination of the two is far more likely to be fatal than either one alone. The prehistoric animals faced not just one catastrophe, but two, unfolding simultaneously and reinforcing each other. This synergistic effect may explain why the extinction was so widespread and so devastating. It wasn’t just a single event that wiped out the dinosaurs and other species; it was a prolonged period of environmental upheaval, driven by a combination of cosmic and terrestrial forces. The Deccan Traps, once relegated to a secondary role in the extinction narrative, are now being recognized as a major player, a silent but deadly accomplice in one of the most dramatic events in Earth’s history.

Climate Change as a Major Driver

The narrative surrounding prehistoric extinctions has long been dominated by dramatic, singular events like asteroid impacts. But increasingly, scientists are recognizing the insidious, pervasive role of climate change – not just as a consequence of these events, but as a powerful driver of extinction in its own right. It’s a sobering thought, isn’t it? To realize that the very forces shaping our planet today were also reshaping life and death millions of years ago. It forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that extinction isn’t always a sudden catastrophe, but often a slow, grinding process driven by shifting environmental conditions. This section will delve into how climate fluctuations, particularly the dramatic warming event known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), impacted prehistoric ecosystems and contributed to the disappearance of numerous species.

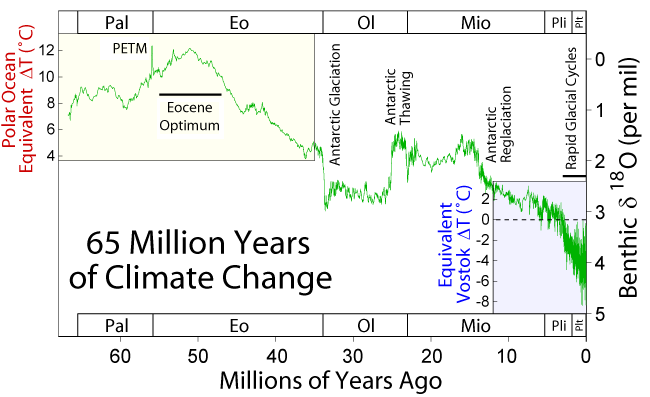

Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM): A Prehistoric Warming Event

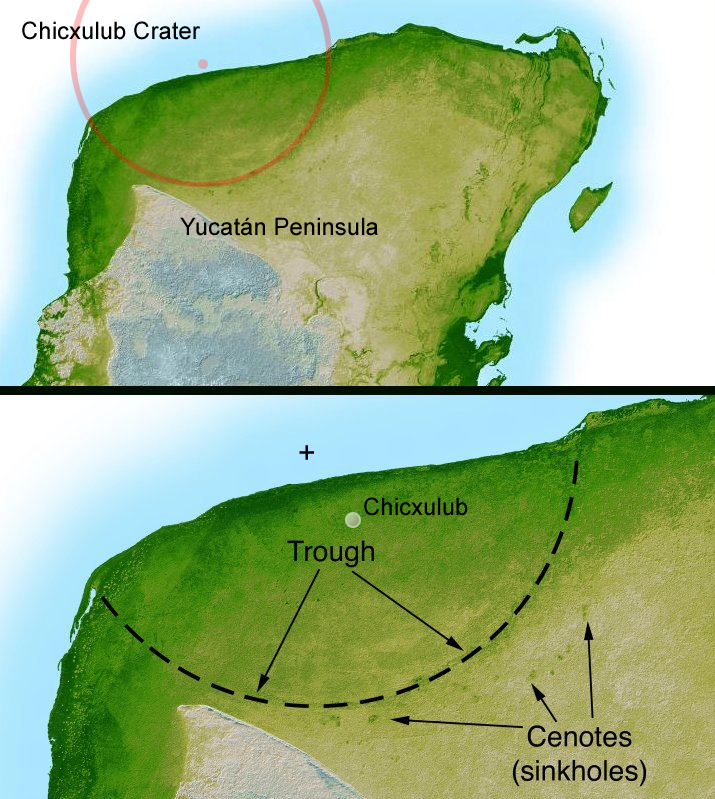

Imagine a world rapidly warming, not over centuries, but over a few thousand years. That’s the PETM, a period roughly 56 million years ago that serves as a chilling analogue for our current climate crisis. It’s a period that paleontologists and climatologists alike study with intense fascination, because it offers a glimpse into how life responds – or fails to respond – to rapid, significant warming. The PETM wasn’t caused by human activity, of course. The leading theory points to massive releases of carbon into the atmosphere, likely from volcanic activity associated with the North Atlantic Igneous Province (NAIP). This release triggered a cascade of effects, including a significant increase in global temperatures – estimates range from 5 to 8 degrees Celsius.

A map illustrating the estimated global temperature anomalies during the PETM highlighting the widespread warming

What makes the PETM so remarkable is the speed of the warming. While past climate shifts often occurred over tens or hundreds of thousands of years, the PETM unfolded over a relatively short geological timeframe. This rapid change didn’t give many species enough time to adapt or migrate. The geological record shows a clear signal: a negative carbon isotope excursion (a decrease in the ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12), indicating the release of large amounts of “light” carbon from sources like methane hydrates. This carbon influx dramatically altered the Earth’s carbon cycle, leading to ocean acidification and widespread environmental stress. It’s a stark reminder that the Earth’s systems are interconnected, and a disruption in one area can have far-reaching consequences. The study of the PETM isn’t just about understanding the past; it’s about refining our models and predictions for the future.

The Impact of Greenhouse Gases on Prehistoric Ecosystems

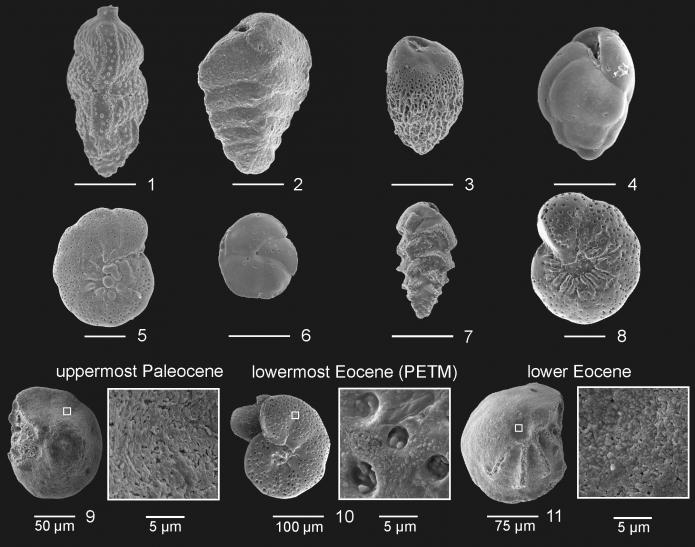

The surge in greenhouse gases during the PETM – primarily carbon dioxide and methane – had a profound impact on prehistoric ecosystems. The warming temperatures led to significant changes in sea levels, ocean currents, and precipitation patterns. Forests expanded into previously cooler regions, while other ecosystems experienced widespread die-offs. The oceans became more acidic, threatening marine organisms with calcium carbonate shells, like foraminifera and corals. This ocean acidification is a particularly worrying parallel to our current situation, as it poses a significant threat to marine biodiversity today.

Microscopic image of fossil foraminifera shells showing evidence of dissolution due to ocean acidification during the PETM

The effects weren’t uniform across the globe. Some regions experienced more dramatic changes than others, and different ecosystems responded in different ways. For example, high-latitude regions experienced the most significant warming, leading to the expansion of warm-water species and the decline of cold-adapted species. In terrestrial ecosystems, we see evidence of shifts in plant communities, with tropical and subtropical plants migrating northward. The fossil record reveals a clear pattern of species turnover, with some species going extinct and others evolving to adapt to the new conditions. The impact on prehistoric animals was substantial. Many smaller mammals, particularly those adapted to cooler climates, struggled to survive. Larger animals, like early horses and crocodiles, also experienced significant changes in their distribution and abundance. It’s a complex picture, but the overarching theme is one of disruption and loss. The PETM demonstrates that even relatively small increases in greenhouse gas concentrations can have devastating consequences for life on Earth.

Gradual vs. Sudden Climate Shifts: Different Extinction Patterns

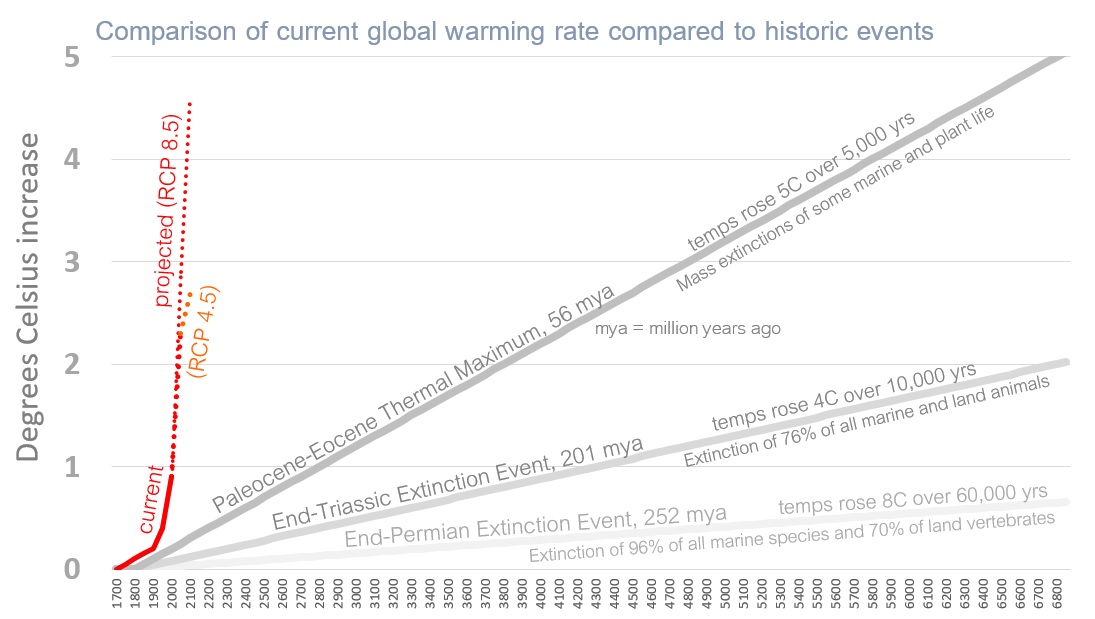

One of the key insights from studying prehistoric extinctions is that the rate of climate change is just as important as the magnitude of change. Gradual climate shifts, occurring over tens or hundreds of thousands of years, typically allow species more time to adapt, migrate, or evolve. While extinctions still occur during gradual shifts, they tend to be less severe and more selective. However, sudden climate shifts, like the PETM, can overwhelm the adaptive capacity of many species, leading to mass extinctions.

A graph illustrating the correlation between the rate of climate change and extinction rates showing a steeper curve for sudden shifts

The difference in extinction patterns is striking. During gradual climate shifts, we often see a gradual decline in species diversity, with some species going extinct and others evolving to fill their ecological niches. This process can take millions of years, but it allows ecosystems to maintain a degree of stability. In contrast, sudden climate shifts often trigger a cascade of extinctions, with many species disappearing in a relatively short period of time. This is because sudden changes disrupt the delicate balance of ecosystems, leaving many species unable to cope with the new conditions. The prehistoric animals that were less adaptable, or had limited geographic ranges, were particularly vulnerable.

Consider the difference between the gradual cooling trend that occurred over millions of years during the late Cenozoic era, and the rapid warming event of the PETM. The gradual cooling led to a relatively slow decline in species diversity, with many species adapting to the colder conditions. The PETM, on the other hand, triggered a more abrupt and widespread extinction event. This highlights the importance of considering the rate of climate change when assessing the risk of extinction. It’s not just about how much the climate changes, but how quickly it changes. This is a critical lesson for us today, as we are currently experiencing a period of rapid climate change driven by human activity. The faster we reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, the better our chances of mitigating the worst impacts of climate change and preserving biodiversity. The past, in this case, is not just prologue; it’s a warning.

Disease and Biological Factors

It’s easy to get caught up in the grand, dramatic narratives of asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions when discussing the extinction of prehistoric animals. These events were undoubtedly monumental, reshaping the planet in ways we can scarcely imagine. But what about the quieter, more insidious forces at play? What about the microscopic battles, the relentless pressures of competition, and the slow erosion of genetic diversity? These biological factors, often relegated to the sidelines, may have been far more significant in driving extinctions than we previously thought. It’s a humbling thought, isn’t it? To consider that some of the most powerful extinction events weren’t caused by cosmic or geological upheavals, but by something as seemingly simple as a virus or a particularly ruthless predator.

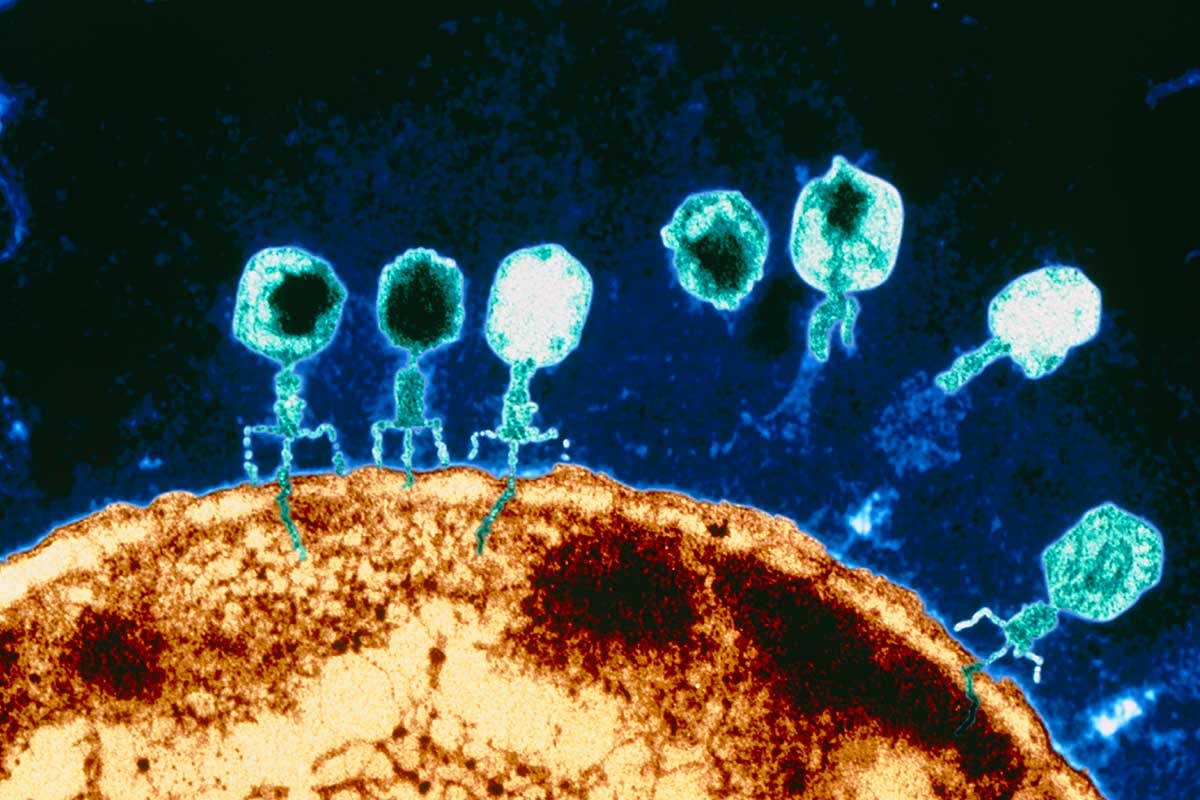

The Spread of Ancient Pathogens: A Hidden Extinction Driver?

Viruses though invisible to the naked eye can have devastating effects on populations

The idea that disease could have played a major role in the extinction of prehistoric animals is gaining traction, and for good reason. We know that pathogens – viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites – are constantly evolving, and that they can have devastating effects on populations, even today. Think about the impact of avian flu on bird populations, or chytridiomycosis on amphibians. Now, imagine these pathogens unleashed on a world populated by creatures with immune systems utterly unprepared for them.

The challenge, of course, is proving this. Fossilized remains rarely preserve evidence of disease. However, scientists are becoming increasingly adept at identifying biomarkers of ancient pathogens in fossilized bones and tissues. For example, researchers have found evidence of bone infections and even possible viral outbreaks in dinosaur fossils. While definitive proof remains elusive, the circumstantial evidence is compelling.

Consider the case of large herbivores. These animals often live in dense populations, making them particularly vulnerable to the rapid spread of infectious diseases. A novel pathogen could sweep through a herd, decimating its numbers and leaving the remaining individuals weakened and susceptible to other threats. This is especially true for species with limited genetic diversity (we’ll get to that later).

But it wasn’t just large animals that were at risk. Even smaller creatures, like insects and marine invertebrates, could have been susceptible to ancient pathogens. A widespread fungal infection, for example, could have wiped out entire colonies of coral or decimated insect populations, triggering cascading effects throughout the ecosystem. The possibilities are truly frightening.

Furthermore, the changing climate following major extinction events could have facilitated the spread of pathogens. As habitats shifted and animals were forced to migrate, they would have come into contact with new pathogens to which they had no immunity. It’s a perfect storm scenario: a vulnerable population, a novel pathogen, and a changing environment. It’s a chilling thought that the very act of seeking refuge could have led to their demise.

Competition and Evolutionary Dead Ends: Losing the Arms Race

The natural world is a relentless competition for resources – food, water, territory, mates. This competition drives evolution, forcing species to adapt and innovate in order to survive. But sometimes, despite their best efforts, species simply can’t keep up. They reach an evolutionary dead end, unable to compete with more successful rivals.

This is particularly true in the context of predator-prey relationships. It’s a classic arms race: predators evolve more effective hunting strategies, while prey evolve more sophisticated defenses. But this arms race isn’t always symmetrical. Sometimes, a predator gains a significant advantage, driving its prey to extinction.

Think about the evolution of flowering plants during the Cretaceous period. These plants were a relatively new innovation, and they quickly diversified, outcompeting many of the older plant species. This, in turn, had a ripple effect on the animals that depended on those plants for food. Herbivores that couldn’t adapt to the new vegetation struggled to survive, and the predators that preyed on them followed suit.

The rise of mammals after the extinction of the dinosaurs is another example. With the dinosaurs gone, mammals were able to diversify and fill the ecological niches that had been previously occupied by their reptilian rivals. This led to a period of rapid mammalian evolution, but it also meant that many of the older mammalian species were outcompeted and driven to extinction.

Competition wasn’t limited to interactions between different species. It also occurred within species. Individuals with traits that gave them a competitive advantage – better hunting skills, more efficient foraging strategies, greater resistance to disease – were more likely to survive and reproduce, passing on those traits to their offspring. This process of natural selection can lead to rapid evolutionary change, but it can also lead to the extinction of less-fit individuals and populations.

It’s important to remember that extinction isn’t always a sudden event. It can be a gradual process, unfolding over thousands or even millions of years. Species may slowly decline in numbers as they are outcompeted by rivals, their habitats are degraded, or their food sources dwindle. By the time scientists discover that a species is in trouble, it may already be too late to save it.

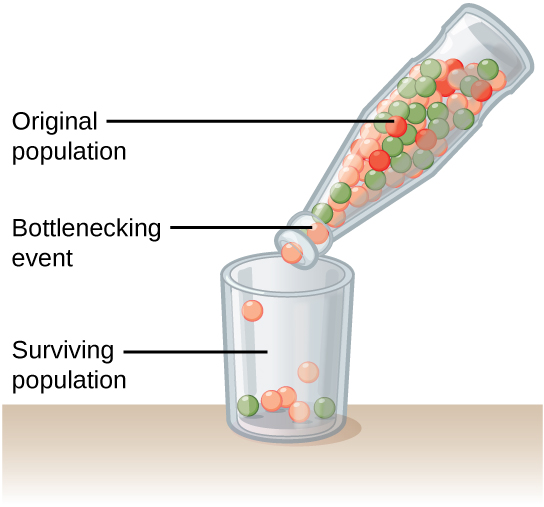

Genetic Bottlenecks and Reduced Biodiversity

A genetic bottleneck reduces genetic diversity within a population

Genetic diversity is the raw material of evolution. It’s the variety of genes within a population that allows it to adapt to changing environments. A population with high genetic diversity is more resilient to disease, climate change, and other threats. But what happens when genetic diversity is lost?

A genetic bottleneck occurs when a population experiences a drastic reduction in size. This can be caused by a variety of factors, including disease outbreaks, natural disasters, and habitat loss. When a population shrinks, it loses genetic diversity. The surviving individuals represent only a small fraction of the original gene pool, and their offspring inherit a limited range of genetic traits.

This loss of genetic diversity can have devastating consequences. A population with low genetic diversity is less able to adapt to changing environments, making it more vulnerable to extinction. It’s like trying to build a house with only a few types of bricks – you’re limited in what you can create.

Many prehistoric animals likely experienced genetic bottlenecks before their eventual extinction. For example, the dinosaurs may have already been in decline for millions of years before the asteroid impact, their populations fragmented and their genetic diversity eroded. This would have made them even more vulnerable to the catastrophic effects of the impact.

The impact of the Chicxulub asteroid itself likely caused widespread genetic bottlenecks. The immediate aftermath of the impact would have been incredibly harsh, with widespread fires, tsunamis, and a prolonged period of darkness. Only the most resilient individuals would have survived, and they would have carried a limited range of genetic traits.

The consequences of reduced biodiversity extend beyond the extinction of individual species. It can also disrupt entire ecosystems. When a keystone species – a species that plays a critical role in maintaining the structure and function of an ecosystem – goes extinct, it can trigger a cascade of extinctions, leading to the collapse of the entire ecosystem.

The loss of genetic diversity is a serious threat to biodiversity today. Human activities, such as habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change, are driving many species towards extinction, and they are also reducing genetic diversity within populations. It’s a dangerous trend, and one that we need to address if we want to preserve the planet’s biodiversity for future generations. The story of prehistoric animals serves as a stark warning: a loss of genetic diversity can have catastrophic consequences.

Rethinking Extinction: It Wasn’t Always Sudden

For so long, the narrative surrounding extinction events has been one of dramatic, swift upheaval – a cosmic bullet or a volcanic inferno wiping the slate clean. But the truth, as paleontologists are increasingly discovering, is far more nuanced. Extinction isn’t always a singular, catastrophic moment; it’s often a process, a series of escalating pressures, and a constant background hum of loss that has characterized life on Earth since its very beginnings. To truly understand why prehistoric animals disappeared, we need to move beyond the blockbuster scenarios and appreciate the subtle, persistent forces at play. It’s a humbling realization, and one that carries profound implications for our own time.

The “Background Extinction Rate”: A Constant Loss of Species

A paleontologist carefully excavating a dinosaur fossil in the badlands illustrating the ongoing discovery of extinct species

The idea of a “background extinction rate” is deceptively simple. It refers to the normal, ongoing rate at which species disappear, even in the absence of major catastrophic events. Think of it as the natural turnover of life. New species evolve, others become outcompeted, and still others simply fail to adapt to changing conditions. This rate isn’t zero. In fact, it’s estimated that even without human influence, species are constantly going extinct. Before the rise of humans, the background extinction rate was estimated to be roughly 1 to 5 extinctions per year. This might seem high, but it’s a slow, gradual process spread across millennia, allowing ecosystems to, to some extent, absorb the losses.

The fossil record, while incomplete, provides glimpses into this constant churn. We find gaps in the lineage of even successful groups, evidence of species that simply faded away without a dramatic event to mark their demise. These aren’t the headline-grabbing extinctions, but they are fundamental to understanding the dynamics of life. Consider the trilobites, those ancient marine arthropods that thrived for nearly 300 million years. Their decline wasn’t a single event, but a gradual waning over tens of millions of years, punctuated by smaller extinction pulses. They weren’t wiped out by an asteroid; they were slowly overtaken by more competitive organisms and changing ocean conditions.

The concept of the background extinction rate is crucial because it provides a baseline against which to measure the severity of mass extinction events. It’s the quiet hum against which the roaring chaos of a catastrophe is heard. Without understanding the normal rate of loss, it’s impossible to accurately assess the magnitude of the crises that have punctuated Earth’s history. It also forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that extinction is a natural part of life, even if the current rate is anything but natural.

Serial Extinctions: A Cascade of Disappearances

A painting depicting a variety of extinct megafauna including woolly mammoths and sabertoothed tigers illustrating the cascading effects of extinction

Often, extinction isn’t a single, isolated event, but a series of interconnected losses – a cascade of disappearances. This is what we call serial extinction. It begins with the loss of key species, often those at the top of the food chain or those that play critical roles in ecosystem function. These initial losses then trigger a ripple effect, leading to the decline and eventual extinction of other species that depend on them.

Imagine a forest ecosystem dominated by a large herbivore. If that herbivore goes extinct, the plants it once grazed on might flourish initially, but this can lead to changes in forest structure, impacting other herbivores, insect populations, and ultimately, the predators that rely on them. The entire ecosystem is destabilized, and further extinctions become more likely.

The end-Permian extinction, the largest known mass extinction event in Earth’s history, is a prime example of serial extinction. It began with massive volcanic eruptions that released enormous amounts of greenhouse gases, causing rapid climate change. This initial shockwave led to the collapse of marine ecosystems, followed by the decline of terrestrial forests. As plant life dwindled, herbivores suffered, and then the carnivores. The extinction wasn’t a single, instantaneous event; it unfolded over tens of thousands of years, with each loss exacerbating the crisis and triggering further declines.

Even the more famous Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction, often attributed solely to the Chicxulub asteroid impact, likely involved a significant element of serial extinction. The impact itself caused widespread devastation, but the subsequent disruption of food chains, the collapse of plant life, and the long-term climate changes all contributed to a cascading series of losses. The prehistoric animals that survived the initial impact faced a drastically altered world, and many succumbed to the long-term consequences.

Understanding serial extinction is vital because it highlights the interconnectedness of life and the potential for seemingly small losses to have far-reaching consequences. It’s a reminder that ecosystems are complex webs, and pulling on one thread can unravel the entire fabric.

The Holocene Extinction: Are We in a Sixth Mass Extinction?

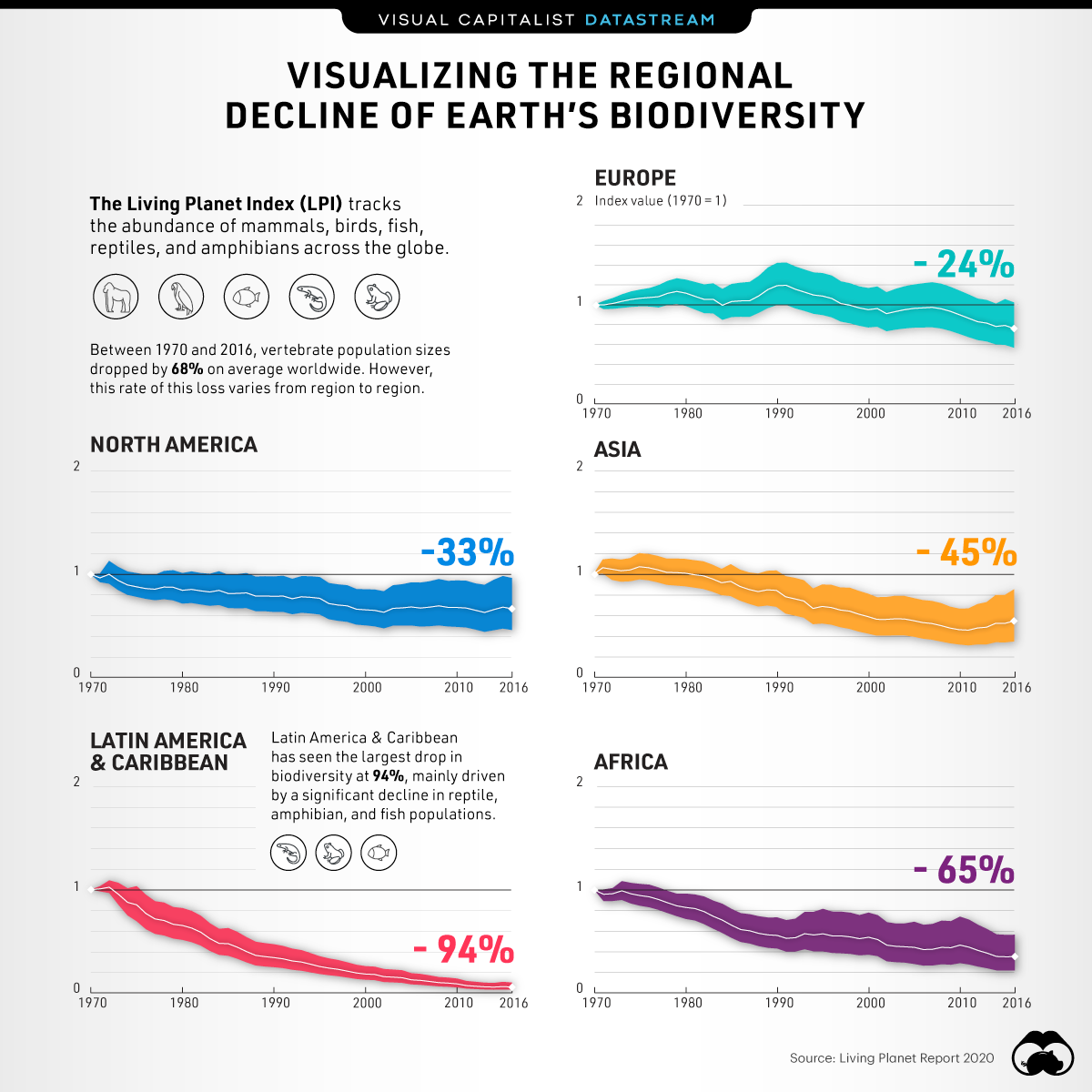

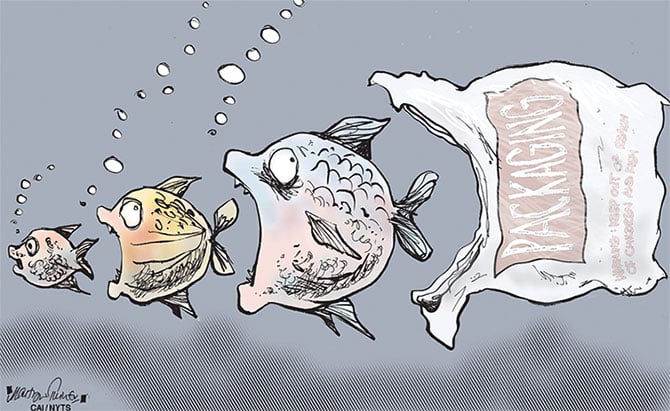

This brings us to the present day, and the unsettling question of whether we are currently experiencing a sixth mass extinction event – the Holocene extinction. Unlike previous mass extinctions driven by natural forces, the Holocene extinction is overwhelmingly caused by human activity. Habitat destruction, overexploitation of resources, pollution, climate change, and the introduction of invasive species are all contributing to a dramatic acceleration in the rate of species loss.

The numbers are stark. Scientists estimate that the current extinction rate is 100 to 1,000 times higher than the background extinction rate. Some projections suggest that we could lose up to half of all species by the end of the century if current trends continue. This isn’t just about losing charismatic megafauna like tigers and elephants; it’s about the loss of countless insects, plants, fungi, and microorganisms that form the foundation of our ecosystems.

The parallels between the Holocene extinction and previous mass extinction events are striking. We are witnessing a rapid disruption of ecosystems, a decline in biodiversity, and a cascading series of losses. The loss of pollinators, for example, threatens agricultural production, while the destruction of forests exacerbates climate change. The consequences are far-reaching and potentially catastrophic.

However, there’s a crucial difference between the Holocene extinction and previous events. We are aware of what’s happening, and we have the power to change course. Unlike the prehistoric animals that faced extinction without understanding the forces arrayed against them, we can recognize the threats and take action to mitigate them. Conservation efforts, sustainable resource management, and a global commitment to reducing our environmental impact are all essential steps.

The question isn’t whether we are in a sixth mass extinction, but whether we can prevent it from reaching its full, devastating potential. It’s a challenge that demands urgent attention, a profound shift in our relationship with the natural world, and a recognition that our fate is inextricably linked to the fate of all other species on Earth. The story of past extinctions isn’t just a tale of loss; it’s a warning, and a call to action. It’s a reminder that the Earth has a remarkable capacity to recover, but only if we give it the chance.

Looking Ahead: Lessons from the Past

The story of prehistoric animals and their extinctions isn’t just a fascinating glimpse into Earth’s deep history; it’s a stark warning, a complex puzzle with pieces that resonate profoundly with our present. For too long, we’ve viewed extinction events as isolated incidents, dramatic punctuation marks in the timeline of life. But the more we learn, the clearer it becomes that extinction is a constant process, a natural part of evolution, albeit one that can be dramatically accelerated by external forces. Understanding these past events, the subtle nuances and the overwhelming catastrophes, is crucial if we hope to navigate the challenges facing our planet today. It’s about recognizing patterns, identifying vulnerabilities, and, ultimately, preventing a future where the story of life on Earth takes a tragic turn.

The Echoes of Past Extinctions in Modern Biodiversity Loss

The sheer scale of past extinction events is almost incomprehensible. The Permian-Triassic extinction, often called “The Great Dying,” wiped out an estimated 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. The Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, famously ending the reign of the dinosaurs, eliminated roughly 76% of plant and animal species. These weren’t just losses of individual species; they were collapses of entire ecosystems, reshaping the course of evolution.

A visual representation of declining biodiversity highlighting the current rate of species loss compared to historical extinction events

What’s particularly unsettling is the growing evidence that we are currently experiencing a sixth mass extinction, often referred to as the Holocene extinction. Unlike previous events driven by asteroid impacts or massive volcanism, this one is overwhelmingly caused by a single species: Homo sapiens. Habitat destruction, pollution, overexploitation of resources, and, most significantly, climate change are driving species to extinction at a rate estimated to be 100 to 1,000 times higher than the background extinction rate.

The parallels are chilling. Just as the Chicxulub impact created a “nuclear winter” scenario, our reliance on fossil fuels is creating a greenhouse effect, altering global temperatures and ocean acidity. Just as volcanic eruptions released toxic gases into the atmosphere, our industrial processes are releasing pollutants that threaten ecosystems. The difference is that we know what we’re doing, and we have the capacity to change course. The question is, will we?

The Fragility of Ecosystems: Lessons from the PETM

The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a period of rapid warming approximately 56 million years ago, offers a particularly relevant case study. During the PETM, global temperatures rose by 5-8°C over a relatively short period (around 20,000 years), driven by a massive release of carbon into the atmosphere. While the exact source of this carbon is still debated, it’s believed to have been a combination of volcanic activity and the release of methane hydrates from the seafloor.

An artists depiction of the Earth during the PETM showing lush vegetation and warmer temperatures

The consequences were profound. Ocean acidification increased, leading to the dissolution of calcium carbonate shells. Many species migrated towards the poles in search of cooler temperatures, but those with limited dispersal abilities or specific habitat requirements struggled to adapt. There was a significant turnover in mammal and plant communities, with some groups thriving while others declined.

The PETM isn’t a perfect analog for modern climate change – the rate of warming is currently much faster, and the scale of human impact is unprecedented. However, it demonstrates the vulnerability of ecosystems to rapid climate shifts and the potential for cascading effects throughout the food web. It highlights the importance of considering not just average temperatures, but also the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, which can push ecosystems beyond their tipping points. The PETM also shows us that even seemingly small changes in atmospheric composition can have dramatic consequences for life on Earth.

The Importance of Genetic Diversity and Resilience

Looking back at species that did survive past extinction events reveals a common thread: genetic diversity. Species with larger populations and greater genetic variation were better equipped to adapt to changing conditions. Genetic diversity provides the raw material for natural selection, allowing populations to evolve in response to new challenges.

Consider the mammals that survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction. These weren’t the large, specialized dinosaurs; they were small, adaptable creatures with relatively high reproductive rates and diverse diets. Their genetic diversity allowed them to exploit new ecological niches and diversify rapidly in the aftermath of the extinction.

Today, many species are facing genetic bottlenecks – reductions in population size that lead to a loss of genetic diversity. This makes them more vulnerable to disease, environmental changes, and inbreeding depression. Conservation efforts that focus on maintaining and restoring genetic diversity are therefore crucial for ensuring the long-term survival of threatened species. This includes protecting large, connected populations, managing captive breeding programs to maximize genetic variation, and addressing the underlying causes of population decline.

Serial Extinctions: A Cascade of Consequences

The concept of “serial extinctions” challenges the traditional view of extinction events as discrete, isolated occurrences. Serial extinctions suggest that major extinction events are often preceded by a series of smaller extinctions, creating a cascade of ecological disruption. These initial losses can weaken ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to subsequent shocks.

For example, the decline of large herbivores can lead to changes in vegetation structure, which in turn affects the populations of smaller herbivores and predators. The loss of keystone species – species that play a disproportionately large role in maintaining ecosystem structure and function – can trigger a domino effect, leading to widespread ecosystem collapse.

A diagram illustrating how the loss of a keystone species can lead to a cascade of extinctions throughout a food web

Understanding serial extinctions is particularly important in the context of modern biodiversity loss. We are already witnessing the decline of many species, and these losses are likely to have cascading effects that we are only beginning to understand. Protecting biodiversity isn’t just about saving individual species; it’s about preserving the integrity of entire ecosystems.

The Holocene Extinction: A Call to Action

The Holocene extinction is unique in that it is driven by a single species – us. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is that our impact is pervasive and multifaceted, affecting ecosystems at every level. The opportunity is that we have the power to change our behavior and mitigate the damage.

The lessons from past extinctions are clear: climate change, habitat destruction, and loss of genetic diversity are major threats to biodiversity. Addressing these threats requires a fundamental shift in our relationship with the natural world. We need to move towards a more sustainable model of development, one that prioritizes conservation, restoration, and responsible resource management.

A group of volunteers planting trees as part of a reforestation effort

This isn’t just an environmental issue; it’s a moral imperative. We have a responsibility to protect the planet for future generations. The fate of prehistoric animals serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of life and the irreversible consequences of extinction. We must learn from the past, act decisively in the present, and strive to create a future where biodiversity thrives. The tiny tails and big stories of the animal kingdom depend on it.

WildWhiskers is a dedicated news platform for animal lovers around the world. From heartwarming stories about pets to the wild journeys of animals in nature, we bring you fun, thoughtful, and adorable content every day. With the slogan “Tiny Tails, Big Stories!”, WildWhiskers is more than just a news site — it’s a community for animal enthusiasts, a place to discover, learn, and share your love for the animal kingdom. Join WildWhiskers and open your heart to the small but magical lives of animals around us!