Have you ever paused to truly consider the incredible lives unfolding beneath the waves? The ocean, covering over 70% of our planet, isn’t just a vast expanse of water – it’s a realm of breathtaking biodiversity, a crucible of evolution, and home to creatures possessing some of the most astonishing survival strategies imaginable. This blog post dives deep – quite literally – into the survival secrets of sea animals, exploring the remarkable adaptations to extreme environments that allow life to flourish in places we humans could barely dream of enduring.

From the crushing pressures and perpetual darkness of the abyssal plains to the vibrant, yet fiercely competitive, coral reefs, and the icy grip of the polar oceans, marine life has consistently defied expectations. We’ll uncover how animals in the sea animals harness the power of bioluminescence to navigate the blackest depths, build bodies capable of withstanding immense pressure, and develop sensory systems that can detect the faintest signals in a world devoid of light.

But it doesn’t stop there. We’ll journey to the dynamic estuaries and mangrove forests, witnessing how creatures master the challenges of fluctuating salinity, and then venture into the open ocean, marveling at the streamlined efficiency of long-distance migrators. It’s truly humbling to realize how much we don’t know about the wonders hidden within our oceans, and this exploration is a testament to the power of natural selection. Learning about sea animals isn’t just about cataloging species; it’s about understanding the resilience of life itself.

This isn’t just a scientific exploration, though. It’s a celebration of the ingenuity of nature, and a crucial reminder of the importance of protecting these fragile ecosystems. Join us as we unravel the Sea Animals‘ most incredible adaptations, and consider what we can do to ensure their survival for generations to come. Prepare to be amazed, inspired, and perhaps, a little bit awestruck.

The Deep Sea: Mastering the Darkness and Pressure

The deep sea. Just the name evokes a sense of mystery, of the unknown, of a world utterly alien to our own. It’s a realm where sunlight fails to penetrate, where the pressure is immense, and where life has evolved in ways that challenge our very understanding of what’s possible. For centuries, this vast underwater expanse remained largely unexplored, a hidden frontier on our own planet. But with advancements in technology, we’re beginning to peel back the layers of this enigmatic environment, revealing a breathtaking diversity of creatures that have mastered the art of survival in the face of extreme adversity. Understanding these adaptations isn’t just about appreciating the wonders of about sea animals; it’s about gaining insights into the fundamental principles of life itself. It’s a testament to the power of evolution and the incredible resilience of nature.

Bioluminescence: Nature’s Underwater Light Show

Imagine a world perpetually shrouded in darkness. How do you find a mate? How do you attract prey? How do you avoid becoming prey yourself? For deep-sea creatures, the answer lies in bioluminescence – the production and emission of light by a living organism. It’s not simply a passive glow; it’s a complex and versatile tool used for a multitude of purposes.

An anglerfish uses bioluminescence to lure prey in the dark depths

The most iconic example is perhaps the anglerfish, with its bioluminescent lure dangling enticingly in front of its gaping maw. This isn’t just a simple light; it’s a carefully crafted beacon, attracting unsuspecting fish directly into the anglerfish’s waiting jaws. But bioluminescence isn’t limited to predation. Many species use it for communication, signaling to potential mates or warning off rivals. Others employ it as a form of camouflage, a technique called counterillumination. By emitting a faint glow from their undersides, they blend in with the faint sunlight filtering down from above, effectively becoming invisible to predators looking up.

The chemistry behind bioluminescence is fascinating. It typically involves a chemical reaction between a light-emitting molecule called luciferin and an enzyme called luciferase. Different species use different types of luciferin and luciferase, resulting in a stunning array of colors and patterns. Some creatures even harbor bioluminescent bacteria within their bodies, forming symbiotic relationships where both organisms benefit. The diversity of bioluminescent displays in the deep sea is truly remarkable, a silent, shimmering language spoken in the darkness. It’s a constant reminder that even in the most extreme environments, life finds a way to shine. This is a key aspect when learning about sea animals and their unique adaptations.

Pressure Resistance: Bodies Built to Withstand the Crush

As you descend into the deep sea, the pressure increases dramatically. For every 10 meters (33 feet) you go down, the pressure increases by one atmosphere. At the deepest point in the ocean, the Mariana Trench, the pressure is over 1,000 times the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level. That’s equivalent to having 50 jumbo jets stacked on top of you! How can any living organism survive such crushing forces?

The answer lies in a combination of physiological and biochemical adaptations. Firstly, deep-sea animals lack the air-filled cavities found in many surface-dwelling creatures. Swim bladders, used for buoyancy, are absent or greatly reduced, eliminating a potential point of collapse. Secondly, their bodies are often composed of water-rich tissues, making them nearly incompressible. This means that the pressure is distributed evenly throughout their bodies, minimizing stress on any single point.

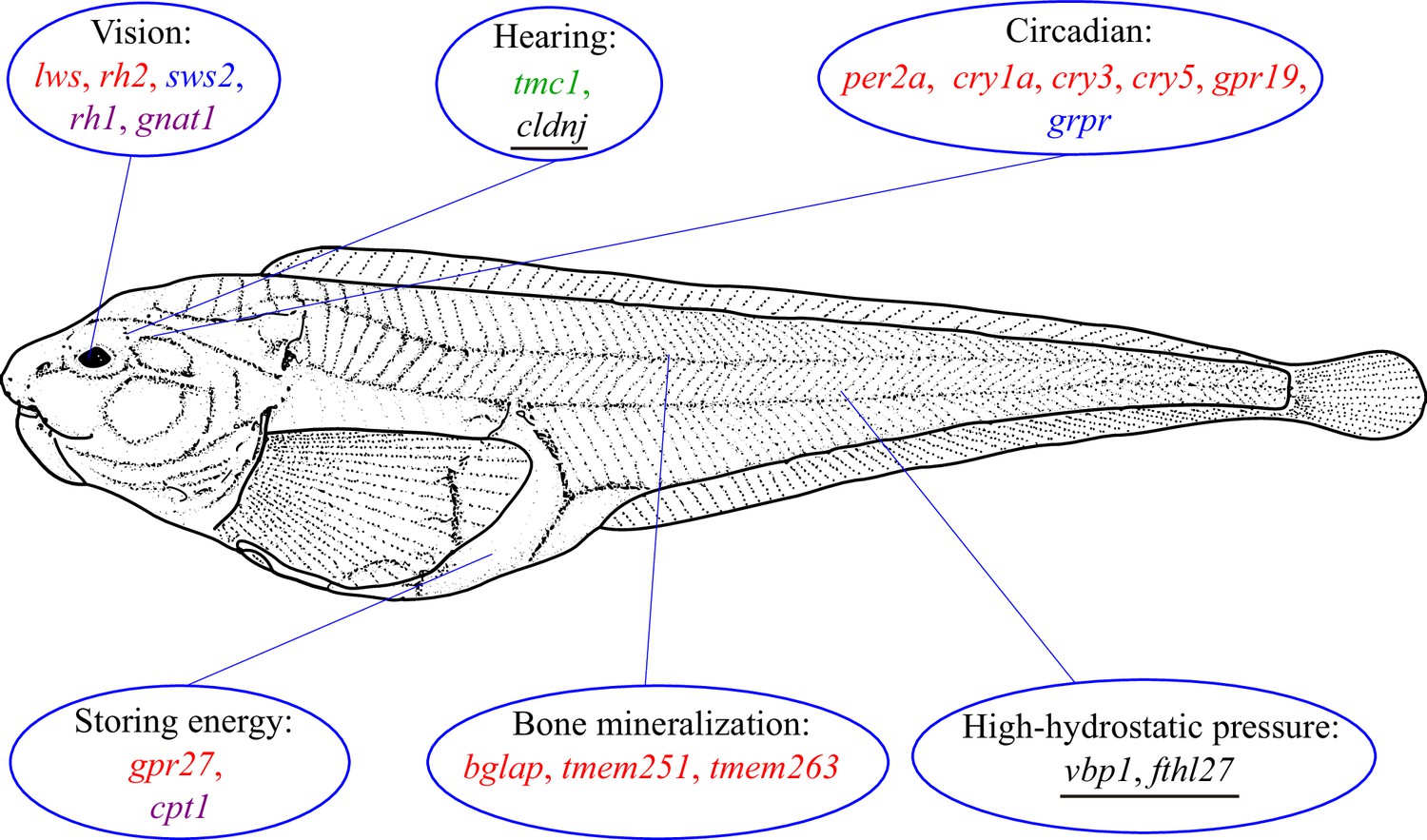

A hadal snailfish adapted to withstand extreme pressure in the deep sea

But it’s not just about physical structure. Deep-sea animals also have unique biochemical adaptations. Their proteins are often stabilized by special molecules called piezolytes, which counteract the disruptive effects of pressure on protein folding. These piezolytes help maintain the functionality of enzymes and other essential proteins, ensuring that cellular processes can continue even under extreme pressure. The cell membranes of deep-sea animals are also different, containing higher levels of unsaturated fatty acids, which help maintain fluidity under pressure.

The study of pressure resistance in deep-sea animals has implications far beyond marine biology. Understanding how these creatures cope with extreme pressure could lead to advancements in materials science, engineering, and even medicine. Imagine being able to design materials that can withstand immense pressure, or develop drugs that can protect cells from damage caused by pressure changes. The deep sea, once again, offers a wealth of knowledge waiting to be unlocked.

Specialized Sensory Systems: Finding Food in the Void

In a world devoid of light, traditional vision is of limited use. So, how do deep-sea animals find food, navigate their surroundings, and locate potential mates? They rely on a suite of highly specialized sensory systems that have evolved to overcome the challenges of the dark abyss.

One of the most important senses is chemoreception, the ability to detect chemicals in the water. Deep-sea animals have highly sensitive olfactory organs that can detect even minute traces of prey or potential mates carried by ocean currents. Some species, like sharks, can detect a single drop of blood in millions of gallons of water.

The lateral line system in fish allows them to detect vibrations and pressure changes in the water

Another crucial sensory system is the lateral line, found in fish and some other aquatic animals. This system consists of a series of pores along the sides of the body that contain sensory cells called neuromasts. These neuromasts detect vibrations and pressure changes in the water, allowing the animal to sense the movement of prey, predators, or obstacles in its path. It’s essentially a sixth sense, providing a detailed picture of the surrounding environment.

Many deep-sea animals also possess enhanced tactile senses, with highly sensitive skin and barbels (whisker-like appendages) that can detect subtle changes in water flow and texture. Some species even use electroreception, the ability to detect electrical fields generated by other organisms. This is particularly useful for locating prey that are hidden in the sediment.

The development of these specialized sensory systems is a testament to the power of natural selection. In the absence of light, other senses have become amplified and refined, allowing deep-sea animals to thrive in a world that would be utterly inhospitable to most surface-dwelling creatures.

Slow Metabolism: Conserving Energy in a Scarce World

The deep sea is not a place of abundance. Food is scarce, and resources are limited. In such an environment, energy conservation is paramount. Deep-sea animals have evolved remarkably slow metabolisms, allowing them to survive for extended periods on minimal food intake.

A slow metabolism means that all physiological processes – from digestion to muscle contraction – occur at a reduced rate. This reduces the animal’s energy expenditure, allowing it to conserve precious resources. Deep-sea animals typically grow very slowly, reproduce late in life, and have long lifespans. This is a trade-off: they may not reproduce as quickly as surface-dwelling species, but they have a higher chance of surviving to reproductive age.

The slow metabolism of the anglerfish allows it to survive long periods without food

The slow metabolism of deep-sea animals is reflected in their body composition. They often have low muscle mass and high levels of fat storage, providing a reserve of energy that can be tapped into when food is scarce. Their digestive systems are also highly efficient, extracting the maximum amount of nutrients from whatever food they manage to find.

This adaptation isn’t limited to just physical characteristics. The very structure of their cells and the efficiency of their biochemical pathways are geared towards minimizing energy expenditure. It’s a holistic approach to survival, where every aspect of the animal’s biology is optimized for energy conservation.

The study of slow metabolism in deep-sea animals has potential implications for human health. Understanding how these creatures can survive for so long on so little energy could lead to breakthroughs in the treatment of metabolic disorders and the development of strategies for extending human lifespan. It’s another example of how the deep sea, a seemingly remote and inaccessible environment, can offer valuable insights into the fundamental processes of life. Learning in the sea animals and their adaptations is crucial for understanding the interconnectedness of life on Earth.

Coral Reefs: Thriving in a Colorful, Competitive World

Coral reefs. The very name conjures images of vibrant colors, teeming life, and an underwater paradise. But beneath the beauty lies a world of intense competition, a constant struggle for survival, and an astonishing array of adaptations that allow creatures to not just exist, but thrive in this incredibly complex ecosystem. It’s a place where evolution has run wild, crafting some of the most ingenious strategies for survival found anywhere in the sea animals. These aren’t just pretty faces; they’re masters of disguise, collaboration, and specialization. Understanding how these animals navigate this world is crucial to appreciating the delicate balance of coral reefs and the urgent need for their conservation.

Camouflage and Mimicry: Blending In to Survive

The coral reef is a visual feast, but for many inhabitants, being seen is a death sentence. Predators lurk around every corner, and the ability to disappear into the background is paramount. This is where camouflage and mimicry come into play. Camouflage isn’t just about being the same color as the coral; it’s a sophisticated art form. Animals employ a range of techniques, from changing color to match their surroundings (like the incredible color-shifting abilities of some octopuses and cuttlefish) to developing patterns that break up their outline, making them harder to detect.

Consider the scorpionfish, a master of disguise. Its skin is covered in bumps and ridges that perfectly mimic the texture of the coral, and its coloration blends seamlessly with the reef’s hues. It sits motionless, appearing as just another part of the landscape, waiting for unsuspecting prey to swim within striking distance. Then there’s the leaf fish, which literally resembles a floating leaf, swaying gently with the current. It’s an astonishing example of how evolution can shape an animal to become virtually invisible.

But camouflage isn’t limited to fish. Many invertebrates, like crabs and shrimp, also employ remarkable camouflage techniques. Some crabs decorate their shells with pieces of coral, algae, and even small anemones, creating a living disguise. This is a fascinating example of active camouflage, where the animal actively seeks out materials to enhance its concealment.

Mimicry takes this a step further. Instead of simply blending in, some animals imitate other creatures, often those that are dangerous or unpalatable. The false-eye butterflyfish, for example, has a large, prominent “eyespot” on its rear fin. This spot resembles the eye of a larger, predatory fish, deterring potential attackers. It’s a clever deception that relies on the attacker’s fear of a larger predator. Learning about sea animals and their survival strategies reveals the incredible ingenuity of nature.

The effectiveness of these strategies is a testament to the power of natural selection. Animals that are better at blending in or mimicking others are more likely to survive and reproduce, passing on their advantageous traits to the next generation. This constant pressure to avoid detection has driven the evolution of some of the most remarkable camouflage and mimicry techniques found in the animal kingdom.

Symbiotic Relationships: Partnerships for Protection and Nourishment

A clownfish finds shelter and protection within the stinging tentacles of an anemone

Life on a coral reef isn’t just about competition; it’s also about cooperation. Symbiotic relationships, where two different species interact in a way that benefits both, are incredibly common. These partnerships can take many forms, from mutualism (where both species benefit) to commensalism (where one species benefits and the other is neither harmed nor helped).

Perhaps the most iconic example of symbiosis on a coral reef is the relationship between clownfish and sea anemones. The anemone’s stinging tentacles provide protection for the clownfish, shielding it from predators. In return, the clownfish cleans the anemone, removing parasites and algae, and may even attract larger fish that the anemone can then capture and eat. The clownfish also provides nutrients to the anemone through its waste products. It’s a win-win situation, a perfect example of mutualism.

But the symbiotic relationships on a coral reef extend far beyond clownfish and anemones. Many coral species have a symbiotic relationship with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae live within the coral’s tissues and provide it with food through photosynthesis. In return, the coral provides the algae with a protected environment and access to sunlight. This relationship is crucial for the health and survival of coral reefs, as it provides the coral with a significant portion of its energy. Without the zooxanthellae, corals would struggle to grow and thrive.

Cleaner wrasses and larger fish also engage in a symbiotic relationship. Cleaner wrasses set up “cleaning stations” on the reef, where larger fish come to have parasites and dead skin removed. The cleaner wrasse gets a meal, and the larger fish gets a health checkup. It’s a fascinating example of how even predators can benefit from cooperation.

These symbiotic relationships highlight the interconnectedness of life on a coral reef. Each species plays a role in the ecosystem, and their interactions are essential for maintaining the reef’s health and biodiversity. Understanding these relationships is crucial for effective conservation efforts.

Specialized Feeding Strategies: Adapting to Niche Diets

The coral reef is a complex and diverse ecosystem, and the animals that live there have evolved a wide range of specialized feeding strategies to exploit the available resources. From algae grazers to coral feeders to predators, each species has found a niche that allows it to thrive.

Parrotfish are perhaps the most well-known example of specialized feeding. They have beak-like mouths that they use to scrape algae off coral. As they feed, they also ingest coral fragments, which they then excrete as sand, playing a crucial role in the formation of sandy beaches. Their constant grazing also helps to keep the coral reef healthy by preventing algae from overgrowing the coral.

Butterflyfish have long, slender snouts that they use to probe into crevices in the coral, feeding on small invertebrates. Their specialized mouths allow them to access food sources that are unavailable to other fish. Different species of butterflyfish have evolved different snout shapes and lengths, allowing them to specialize on different types of prey.

Moray eels are ambush predators that lie in wait in crevices in the coral, waiting for unsuspecting fish to swim by. They have powerful jaws and sharp teeth that they use to quickly snatch their prey. Their camouflage helps them to blend in with the reef, making them even more effective predators.

Then there are the coral polyps themselves, which are filter feeders, capturing plankton and other small organisms from the water column. They use their tentacles to capture prey, and their stinging cells to immobilize it.

The diversity of feeding strategies on a coral reef is a testament to the power of natural selection. Animals that are able to efficiently exploit a specific food source are more likely to survive and reproduce, leading to the evolution of increasingly specialized feeding adaptations. This specialization also reduces competition between species, allowing more species to coexist on the reef. It’s a fascinating example of how evolution can shape an animal’s morphology and behavior to fit its ecological niche. Sea Animals have adapted in incredible ways to survive.

Rapid Reproduction: Ensuring Species Survival in a Fragile Ecosystem

Mass coral spawning event releasing eggs and sperm into the water

Coral reefs are beautiful, but they are also incredibly fragile ecosystems. They are threatened by a variety of factors, including pollution, overfishing, and climate change. In such a vulnerable environment, rapid reproduction is essential for ensuring the survival of species.

Many coral reef animals have evolved strategies to maximize their reproductive output. Some species, like many fish, reproduce throughout the year, releasing eggs and sperm into the water column on a regular basis. This allows them to take advantage of favorable conditions whenever they arise.

Other species, like many corals, engage in mass spawning events. These events occur only once a year, often triggered by the full moon, and involve the simultaneous release of eggs and sperm by thousands of corals. This increases the chances of fertilization and ensures that a large number of larvae are released into the water column. The timing of these events is crucial, and corals rely on a variety of cues, including water temperature, light levels, and lunar cycles, to coordinate their spawning.

Some invertebrates, like sea urchins, have a complex life cycle that involves both sexual and asexual reproduction. They can reproduce sexually by releasing eggs and sperm into the water column, but they can also reproduce asexually by fragmentation, where a piece of the urchin breaks off and develops into a new individual.

The rapid reproductive rates of many coral reef animals are a testament to the selective pressure imposed by the fragility of the ecosystem. Animals that are able to reproduce quickly are more likely to recover from disturbances, such as storms or outbreaks of disease. However, even rapid reproduction cannot compensate for the severe threats facing coral reefs today. Conservation efforts are essential to protect these valuable ecosystems and the incredible diversity of life they support. Understanding about sea animals reproductive strategies is vital for conservation.

Polar Oceans: Enduring the Cold and Ice

The polar regions – the Arctic and Antarctic – represent some of the most challenging environments on Earth. For sea animals, life here is a constant battle against the relentless cold, the presence of ice, and the seasonal extremes of light and darkness. Yet, despite these hardships, a remarkable diversity of creatures not only survive but thrive in these icy realms. Their adaptations are nothing short of extraordinary, showcasing the power of evolution to overcome even the most daunting obstacles. It’s a testament to the resilience of life, and a fascinating area to explore when considering about sea animals and their incredible abilities.

Blubber and Insulation: Staying Warm in Freezing Waters

A humpback whale breaching in the Arctic showcasing its massive size and blubber layer

The most immediate and visually apparent adaptation to the frigid polar waters is the development of thick layers of blubber. Blubber isn’t just fat; it’s a specialized tissue composed of adipose cells packed with oil. This oil acts as an incredibly effective insulator, significantly reducing heat loss to the surrounding water. Think of it as nature’s wetsuit, but far more efficient. Sea animals like whales, seals, and walruses rely heavily on blubber for thermoregulation. The thickness of the blubber layer varies depending on the species and its habitat. For example, the bowhead whale, which lives in the Arctic year-round, boasts a blubber layer that can be over 50 centimeters (20 inches) thick! This massive insulation allows them to maintain a stable core body temperature even in water that’s close to freezing.

But blubber isn’t just about insulation. It also serves as an energy reserve, crucial during periods of food scarcity, particularly during the long polar winters. When food is plentiful, animals build up their blubber stores, providing a vital source of energy when prey is scarce. This dual function makes blubber an incredibly valuable adaptation.

Beyond blubber, many polar sea animals also possess dense fur or feathers that provide an additional layer of insulation. Sea otters, for instance, have the densest fur of any mammal – up to a million hairs per square inch! This creates a layer of air trapped close to the skin, further minimizing heat loss. Penguins, while birds, exhibit similar principles with their tightly packed feathers, creating a waterproof and insulating barrier. The structure of these feathers is unique, interlocking to trap air and prevent water from reaching the skin. Even the arrangement of scales in some fish contributes to insulation by reducing water flow and minimizing heat transfer.

Antifreeze Proteins: Preventing Ice Crystal Formation

Microscopic view of arctic fish blood showing antifreeze proteins preventing ice crystal formation

Even with thick blubber and insulation, the challenge of preventing ice crystal formation within the body fluids is significant. Ice crystals can damage cells and tissues, leading to organ failure and ultimately, death. Polar sea animals have evolved a remarkable solution: antifreeze proteins (AFPs).

These specialized proteins bind to tiny ice crystals as they begin to form, preventing them from growing larger and causing damage. They don’t lower the freezing point of the blood, but rather inhibit the growth of ice crystals. It’s a subtle but crucial difference. AFPs are found in a variety of polar fish, including the Arctic cod, and even in some invertebrates like Antarctic krill.

The fascinating thing about AFPs is that they have evolved independently in several different species, demonstrating a powerful example of convergent evolution. Different species have developed different types of AFPs, each with slightly different structures and mechanisms of action. Scientists are actively studying AFPs, not only to understand the biology of polar sea animals but also for potential applications in cryopreservation – the preservation of biological tissues at low temperatures – and even in preventing ice formation on aircraft wings!

The concentration of AFPs in the blood varies depending on the species and the temperature of the water. Animals living in colder waters generally have higher concentrations of AFPs. This adaptation allows them to survive in environments where the water temperature is below the freezing point of their body fluids. It’s a truly remarkable biochemical feat.

Migration Patterns: Following the Food and Avoiding the Ice

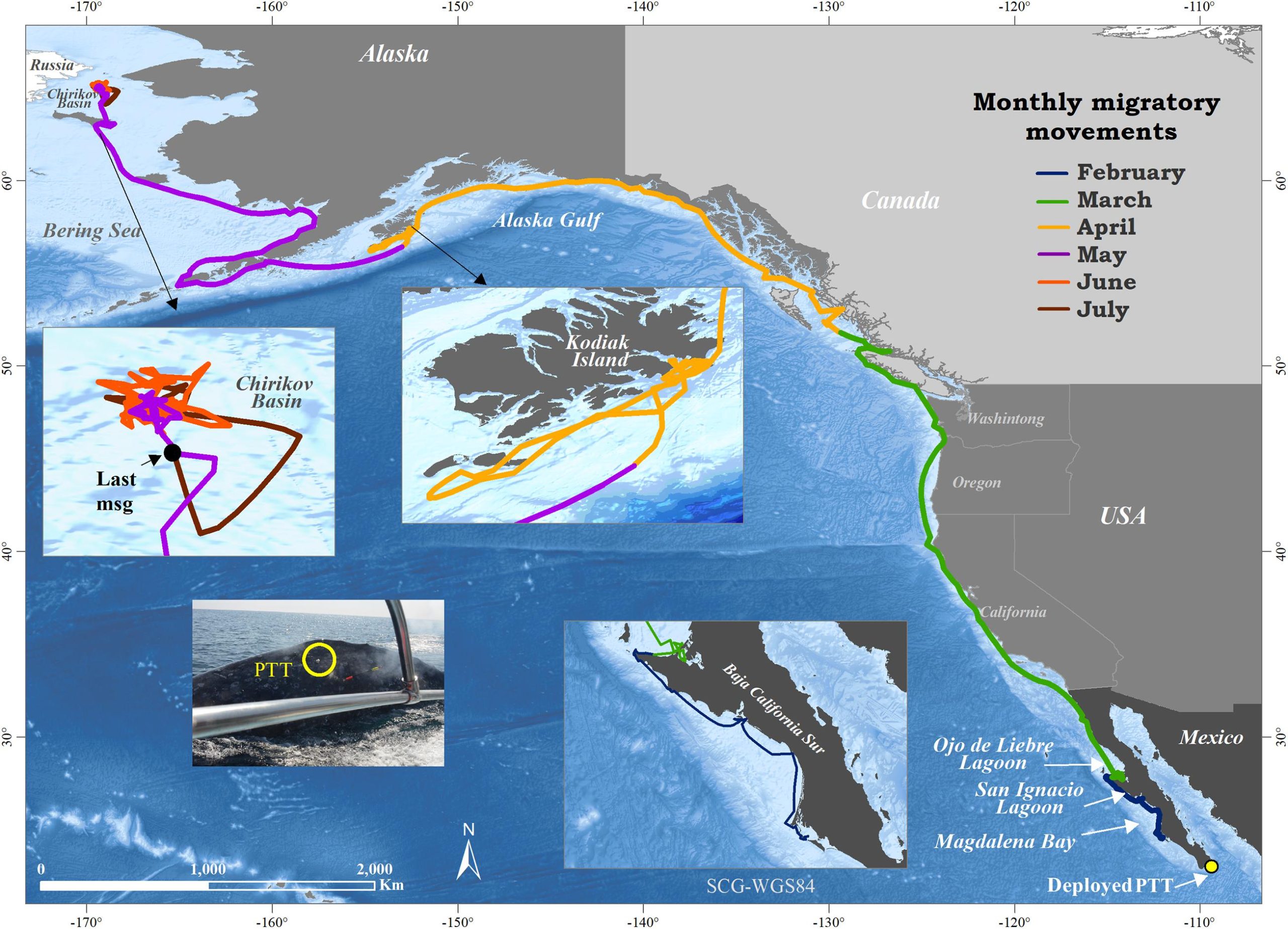

A gray whale migrating from the Arctic to the warmer waters of Baja California for breeding

For many polar sea animals, simply enduring the cold isn’t enough. They also need to find food and avoid being trapped by expanding sea ice. This often leads to dramatic migration patterns. These journeys can be incredibly long and arduous, requiring immense energy expenditure.

Gray whales, for example, undertake one of the longest migrations of any mammal, traveling over 20,000 kilometers (12,000 miles) round trip between their Arctic feeding grounds and their breeding lagoons in Baja California, Mexico. They spend the summer months feeding on benthic invertebrates in the Arctic, building up fat reserves for the long journey south. The migration is timed to coincide with the availability of food and the avoidance of ice.

Similarly, many species of seals and seabirds migrate south during the winter months, following the retreating ice edge and seeking out areas with more abundant food. The timing of these migrations is often triggered by changes in day length and water temperature.

However, not all polar sea animals migrate. Some, like the beluga whale and the narwhal, are able to remain in the Arctic year-round, relying on their adaptations – blubber, AFPs, and the ability to find breathing holes in the ice – to survive the harsh winter conditions. These resident species often exhibit unique behaviors, such as using their powerful beaks to break through thin ice to access air.

The changing climate is significantly impacting migration patterns. As sea ice melts earlier and forms later, the timing of migrations is becoming increasingly disrupted, potentially leading to mismatches between the availability of food and the arrival of migratory species. This is a major concern for the long-term survival of many polar sea animals.

Physiological Adaptations to Extreme Cold: Maintaining Body Functions

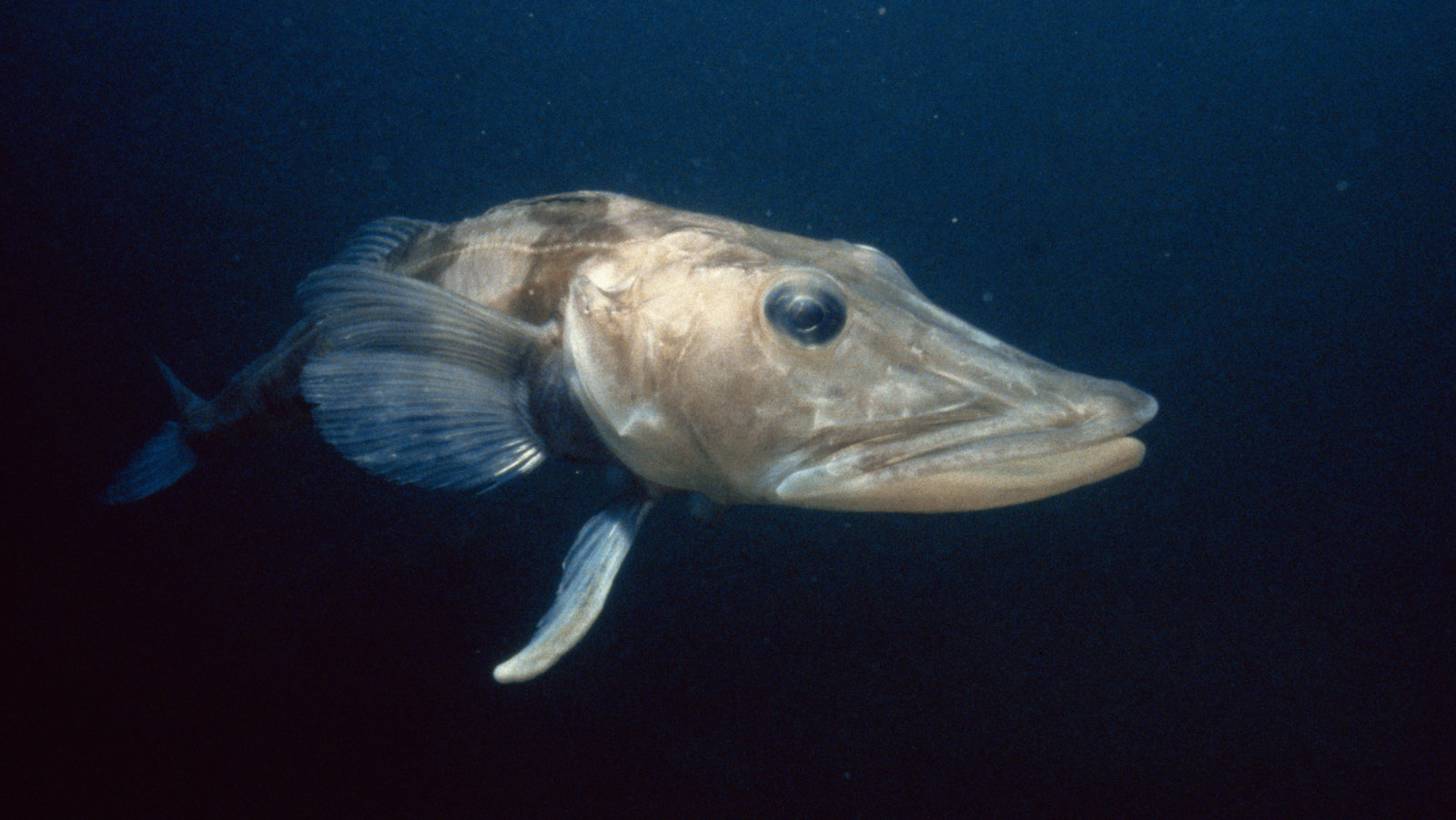

An Antarctic icefish showing its transparent blood lacking hemoglobin

Beyond blubber, AFPs, and migration, polar sea animals exhibit a range of other physiological adaptations that allow them to function effectively in extreme cold. These adaptations affect everything from their circulatory systems to their metabolic rates.

One of the most striking examples is found in Antarctic icefish. These fish have evolved to live in waters that are consistently below 0°C (32°F). Remarkably, they lack hemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen in the blood of most vertebrates. This means their blood is almost transparent! The absence of hemoglobin is thought to be an adaptation to the cold, as hemoglobin becomes less efficient at releasing oxygen at low temperatures. Icefish rely on other mechanisms to deliver oxygen to their tissues, such as increased blood volume and a lower metabolic rate.

Many polar sea animals also have specialized circulatory systems that help to conserve heat. Countercurrent exchange systems are particularly important. In these systems, warm arterial blood flowing to the extremities passes close to cold venous blood returning from the extremities. This allows heat to be transferred from the artery to the vein, warming the venous blood and reducing heat loss from the body. This is particularly well-developed in the flippers and fins of seals and whales.

Furthermore, polar sea animals often have lower metabolic rates than their counterparts in warmer climates. This reduces their energy expenditure and helps them to conserve resources in a food-limited environment. However, this also means that they are more vulnerable to changes in food availability.

Understanding these physiological adaptations is crucial for predicting how polar sea animals will respond to the challenges of climate change. As the Arctic and Antarctic continue to warm, these creatures will face increasing stress, and their ability to adapt will be tested like never before. The study of about sea animals in these extreme environments provides invaluable insights into the limits of life and the importance of protecting these fragile ecosystems.

Estuaries and Mangrove Forests: Adapting to Changing Salinity

Estuaries and mangrove forests represent incredibly dynamic and challenging environments for sea animals. These aren’t the vast, relatively stable conditions of the open ocean, nor the crushing darkness of the deep sea. Instead, they are places of constant flux, where freshwater from rivers meets the saltwater of the ocean, creating a gradient of salinity that shifts with the tides, rainfall, and river flow. This fluctuating environment demands remarkable adaptations from the creatures that call these places home. It’s a testament to the power of evolution that such a rich biodiversity thrives in these seemingly harsh conditions. Thinking about it, it’s almost like these animals are constantly negotiating a compromise, balancing the need to maintain internal stability with the ever-changing world around them.

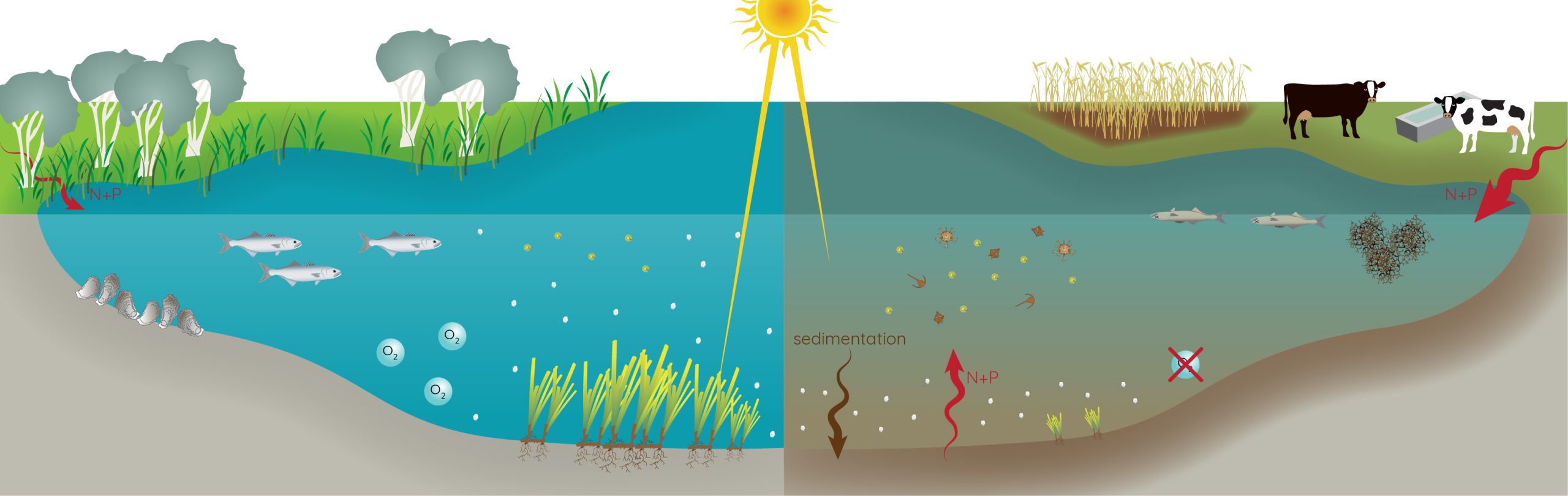

Osmoregulation: Maintaining Internal Salt Balance

A diagram illustrating the mixing of freshwater and saltwater in an estuary

The core challenge for sea animals living in estuaries and mangrove forests is osmoregulation – the process of maintaining a stable internal salt concentration despite variations in the surrounding environment. This is a fundamental physiological hurdle. Imagine trying to keep the saltiness of your blood constant when you’re being constantly splashed with both fresh and saltwater! Different species employ different strategies, and these strategies often dictate where within the estuary they can survive.

For many marine fish, the ocean is a relatively stable environment in terms of salinity. Their bodies are adapted to lose water to the surrounding saltwater through osmosis, and they actively drink seawater to compensate, excreting excess salt through their gills and kidneys. However, when these fish enter an estuary, the lower salinity means they start to gain water and lose salts. Their osmoregulatory systems are thrown into disarray. They have to reduce drinking, and their gills and kidneys have to work harder to conserve salts.

Freshwater fish, on the other hand, are adapted to gain water and lose salts in their environment. They don’t drink much water, and their kidneys produce large volumes of dilute urine. When they enter an estuary, they face the opposite problem – they start to lose water and gain salts. They need to drink more water and reduce urine production.

But it’s not just fish. Crabs, shrimp, and other invertebrates also face these challenges. Many estuarine invertebrates are osmoconformers, meaning they allow their internal salt concentration to fluctuate with the surrounding water. This is a simpler strategy, but it limits their tolerance to extreme salinity changes. Others, like some crabs, have highly efficient osmoregulatory systems that allow them to maintain a stable internal environment even in highly variable conditions. The fiddler crab, for example, is a master of osmoregulation, able to thrive in the mudflats of estuaries where salinity can change dramatically throughout the day. The ability to regulate internal salt balance is truly a cornerstone of survival about sea animals in these environments.

Specialized Gills: Extracting Oxygen from Variable Water

An aerial view of a lush mangrove forest showcasing the intricate root systems

Salinity isn’t the only variable in estuaries and mangrove forests. The mixing of freshwater and saltwater also affects oxygen levels. Freshwater typically holds less dissolved oxygen than saltwater. Furthermore, the decomposition of organic matter in these environments – fallen leaves, decaying plants, and animal waste – consumes oxygen, creating areas of low oxygen concentration, sometimes even hypoxia (very low oxygen). This presents another significant challenge for sea animals: how to extract enough oxygen from the water to survive.

Many estuarine fish have evolved specialized gills that are more efficient at extracting oxygen from water with low oxygen content. These gills often have a larger surface area, allowing for more oxygen uptake. Some species also have the ability to breathe air, supplementing their oxygen intake from the water. The mudskipper, a fascinating fish we’ll discuss later, is a prime example of this adaptation.

Beyond the physical structure of the gills, some sea animals exhibit behavioral adaptations to cope with low oxygen levels. They may move to areas with higher oxygen concentrations, or they may reduce their activity levels to conserve oxygen. Some species even enter a state of dormancy, slowing down their metabolism to minimize oxygen consumption.

The structure of mangrove forests themselves plays a crucial role in oxygenating the water. The intricate network of prop roots provides a large surface area for oxygen exchange, and the leaves of the mangrove trees produce oxygen through photosynthesis. This creates a microenvironment within the mangrove forest that is more oxygenated than the surrounding water. It’s a beautiful example of how the physical environment and the sea animals within it are intricately linked.

Behavioral Adaptations: Avoiding Extreme Salinity Fluctuations

A mudskipper perched on a mangrove root showcasing its ability to move on land

While physiological adaptations like osmoregulation and specialized gills are essential, sea animals also employ a range of behavioral adaptations to minimize their exposure to extreme salinity fluctuations. These adaptations are often more immediate and flexible than physiological changes, allowing animals to respond quickly to changing conditions.

One common strategy is vertical migration. Some fish and invertebrates move up and down in the water column to find areas with more favorable salinity levels. For example, during periods of heavy rainfall, when the salinity near the surface drops, they may move to deeper waters where the salinity is more stable.

Another strategy is horizontal migration. Animals may move into or out of estuaries and mangrove forests in response to salinity changes. Many marine fish migrate into estuaries to breed, taking advantage of the sheltered waters and abundant food resources. However, they may move back out to sea when the salinity becomes too low or too high.

Some sea animals simply avoid areas with extreme salinity fluctuations altogether. They may prefer to live in specific zones within the estuary where the salinity is more stable. For example, some species are found primarily in the upper reaches of the estuary, where the salinity is lower, while others are found in the lower reaches, where the salinity is higher.

The timing of activity is also important. Some species are more active during periods of stable salinity, while others are more tolerant of fluctuations and can forage even when conditions are challenging. Understanding these behavioral patterns is crucial for understanding the distribution and abundance of sea animals in these dynamic environments.

Root Systems and Mudskippers: Life Between Two Worlds

The complex and supportive root system of a mangrove tree underwater

Mangrove forests are defined by their incredible root systems. These aren’t just anchors for the trees; they create a complex three-dimensional habitat that provides shelter, breeding grounds, and foraging opportunities for a vast array of sea animals. The roots act as nurseries for juvenile fish and invertebrates, protecting them from predators and providing them with a rich source of food. They also trap sediment, helping to stabilize the shoreline and prevent erosion.

But perhaps the most iconic inhabitant of mangrove forests is the mudskipper. These remarkable fish have evolved a suite of adaptations that allow them to thrive both in and out of the water. They can breathe air through their skin and the lining of their mouth and throat, allowing them to survive for extended periods on land. They use their pectoral fins to “walk” across the mudflats, and their eyes are positioned on top of their head, giving them a wide field of vision.

Mudskippers are opportunistic feeders, consuming a variety of invertebrates, algae, and detritus. They are also territorial, defending their small patches of mud from rivals. Their ability to live and thrive in this intertidal zone, constantly shifting between water and land, is a testament to the power of adaptation. They truly embody the spirit of these unique ecosystems. They are a perfect example of about sea animals that have successfully navigated the challenges of a fluctuating environment. Observing a mudskipper in its natural habitat is a humbling reminder of the incredible diversity and resilience of life in the sea animals.

Open Ocean: Navigating Vastness and Finding Food

The open ocean. Just the phrase evokes a sense of awe, of limitless blue stretching to the horizon. It’s a realm of incredible beauty, but also one of immense challenge for the creatures that call it home. Unlike the relatively structured environments of coral reefs or estuaries, the open ocean is a vast, dynamic expanse. Resources are often sparsely distributed, and survival demands exceptional adaptations. This section will delve into the remarkable strategies sea animals employ to thrive in this seemingly empty wilderness, focusing on how they overcome the hurdles of distance, drag, oxygen availability, and temperature regulation. It’s a testament to the power of evolution, showcasing how life finds a way, even in the most unforgiving environments. Understanding these adaptations isn’t just about appreciating the ingenuity of nature; it’s crucial for understanding the health of our planet, as the open ocean plays a vital role in global climate regulation and biodiversity.

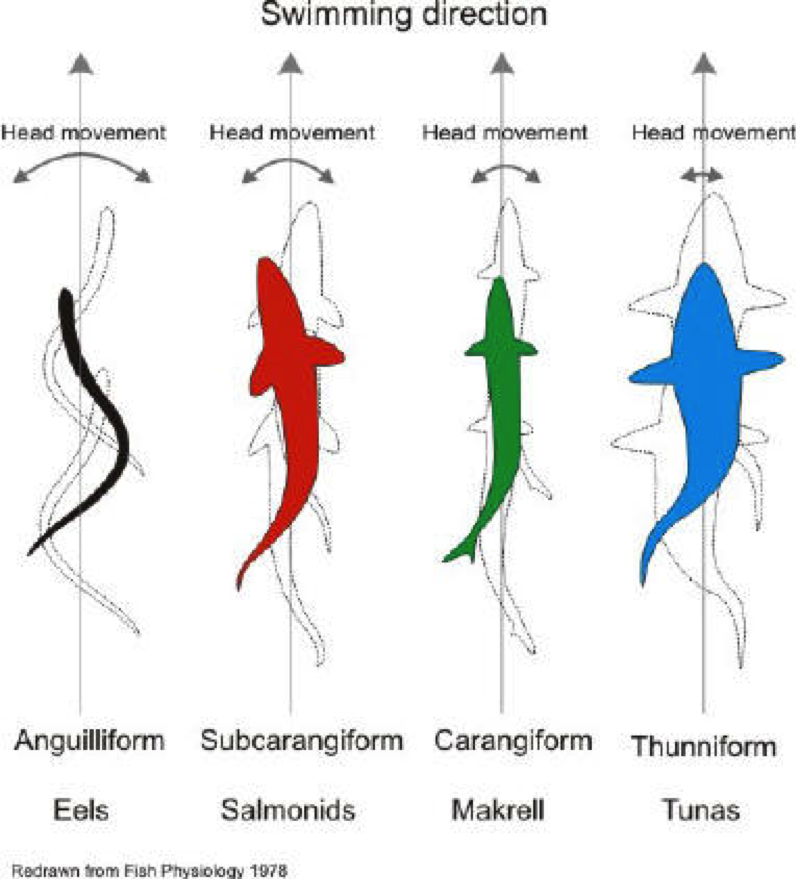

Streamlined Body Shapes: Reducing Drag for Efficient Swimming

Imagine trying to run through water – it’s significantly harder than running through air, right? That’s because of drag, the resistance a fluid exerts on a moving object. In the open ocean, where animals often need to travel vast distances to find food or mates, minimizing drag is paramount. This is where streamlined body shapes come into play.

Think of a tuna, a shark, or even a dolphin. What do they all have in common? Their bodies are fusiform – meaning spindle-shaped, tapering at both ends. This shape, honed by millions of years of evolution, allows water to flow smoothly around the animal, reducing turbulence and therefore, drag. It’s the same principle behind the design of a ship’s hull or an airplane wing.

A tuna demonstrating its streamlined body shape perfectly adapted for efficient swimming in the open ocean

But streamlining isn’t just about the overall body shape. It extends to finer details. Many open ocean fish have deeply forked tails, which provide powerful propulsion with minimal energy expenditure. Their scales are often small and tightly overlapping, creating a smooth surface that further reduces friction. Even the placement of fins is crucial. They’re positioned to provide stability and maneuverability without creating unnecessary drag.

Consider the sailfish, one of the fastest fish in the ocean. Its spear-like bill isn’t just for catching prey; it also contributes to its streamlined profile. The sailfish can reach speeds of over 68 mph (110 km/h), a feat only possible thanks to its incredibly efficient hydrodynamics. This isn’t just about speed; it’s about conserving energy. Every bit of drag reduced translates into less energy expended, allowing these animals to travel further and forage more effectively. The study of about sea animals and their hydrodynamics is a fascinating field, revealing the intricate relationship between form and function.

Long-Distance Migration: Following Currents and Prey

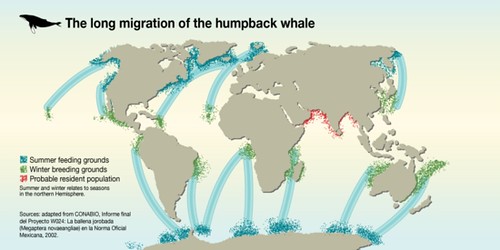

The open ocean isn’t a static environment. Currents, temperature gradients, and the distribution of prey all shift over time. For many sea animals, simply staying put isn’t an option. They must embark on long-distance migrations to find food, breeding grounds, or suitable temperatures. These journeys can be truly epic, spanning thousands of miles and taking months, even years, to complete.

Take the humpback whale, for example. Every year, these magnificent creatures undertake one of the longest migrations of any mammal, traveling from their feeding grounds in polar waters to their breeding grounds in tropical waters. The journey can be over 5,000 miles (8,000 km) each way! But why? The cold, nutrient-rich polar waters provide abundant krill and small fish, essential for building up energy reserves. The warmer tropical waters offer a safe haven for calving and mating.

A map illustrating the incredible migration route of humpback whales showcasing their journey between feeding and breeding grounds

But whales aren’t the only long-distance travelers. Sea turtles, sharks, tuna, and even some seabirds undertake remarkable migrations. They navigate using a combination of cues, including the Earth’s magnetic field, the position of the sun and stars, and even the smell of their natal beaches.

Following ocean currents is a key strategy for many migrating species. Currents can provide a “free ride,” reducing the energy expenditure required for swimming. They also concentrate prey, making it easier for animals to find food along the way. The Gulf Stream, for instance, is a major migratory pathway for tuna, sharks, and sea turtles. Understanding these migratory patterns is crucial for conservation efforts. Protecting key stopover sites and ensuring the health of migratory routes are essential for the survival of these species. The study of in the sea animals migration patterns is a complex and ongoing process, revealing the interconnectedness of marine ecosystems.

Efficient Oxygen Extraction: Maximizing Oxygen Uptake from Water

Water holds significantly less oxygen than air. This presents a major challenge for sea animals, who rely on oxygen to fuel their metabolic processes. To overcome this hurdle, they’ve evolved a variety of mechanisms for efficient oxygen extraction.

Gills are the primary organs for oxygen uptake in fish and many other marine invertebrates. But gills aren’t just simple filters. They’re highly specialized structures with a large surface area, maximizing contact with the water. The filaments within the gills are covered in tiny lamellae, which further increase the surface area.

A detailed illustration of fish gills highlighting the lamellae and their role in efficient oxygen extraction from water

But simply having a large surface area isn’t enough. Fish also employ a process called countercurrent exchange. In this system, water flows over the gills in one direction, while blood flows through the gill filaments in the opposite direction. This creates a concentration gradient, ensuring that blood always encounters water with a higher oxygen concentration. This allows fish to extract a much higher percentage of oxygen from the water than would otherwise be possible.

Mammals and birds, which breathe air, have also adapted to the challenges of diving. They can hold their breath for extended periods by slowing their heart rate, reducing blood flow to non-essential organs, and storing oxygen in their muscles. Seals and whales have a higher concentration of myoglobin, an oxygen-binding protein, in their muscles than terrestrial mammals. This allows them to store more oxygen and continue swimming even when their lungs are empty. The ability to efficiently extract and utilize oxygen is fundamental to the survival of Sea Animals in the open ocean.

Countercurrent Exchange Systems: Conserving Heat in Cold Waters

The open ocean can be a frigid place, especially in polar regions. Maintaining a stable body temperature is crucial for sea animals, as their metabolic processes are sensitive to temperature fluctuations. Many species employ countercurrent exchange systems not only for oxygen extraction but also for conserving heat.

This system works by arranging arteries and veins in close proximity. Arteries carry warm blood from the heart to the extremities, while veins carry cold blood back to the heart. As the warm arterial blood flows past the cold venous blood, heat is transferred from the artery to the vein. This warms the venous blood before it returns to the heart, reducing heat loss.

A diagram illustrating the countercurrent exchange system in a whale flipper showing how heat is conserved by transferring it between arteries and veins

This is particularly important in the flippers, fins, and tails of marine mammals and fish. These extremities are exposed to the cold water and are prone to heat loss. By using countercurrent exchange, these animals can minimize heat loss and maintain a stable body temperature.

Sharks also utilize countercurrent exchange in their muscles. This allows them to maintain a higher muscle temperature than the surrounding water, enhancing their swimming performance. The efficiency of these systems is remarkable, allowing these animals to thrive in environments where they would otherwise struggle to survive. The study of about sea animals thermoregulation reveals the incredible adaptations that allow them to conquer even the coldest corners of the ocean.

Resilience and the Future of Marine Life

The ocean, a vast and mysterious realm, has always been a source of wonder and inspiration. But beneath the surface of breathtaking beauty lies a growing concern: the future of marine life. For millennia, sea animals have demonstrated an incredible capacity for resilience, adapting to shifting environments and overcoming challenges. However, the pace and scale of modern threats – climate change, pollution, overfishing, and habitat destruction – are testing these limits like never before. Understanding this resilience, and the factors that contribute to it, is crucial if we hope to safeguard the incredible biodiversity in the sea animals for generations to come. This isn’t just about preserving pretty creatures; it’s about maintaining the health of the planet, as the ocean plays a vital role in regulating climate, providing oxygen, and supporting countless livelihoods.

The Capacity for Adaptation: Lessons from the Past

Marine life has weathered significant environmental changes throughout Earth’s history. The fossil record is replete with examples of species evolving to survive dramatic shifts in temperature, sea level, and ocean chemistry. Consider the coelacanth, often called a “living fossil.” This ancient fish, thought to have gone extinct 66 million years ago, was rediscovered in 1938 off the coast of South Africa. Its survival is a testament to its ability to adapt to changing conditions over immense timescales.

Similarly, coral reefs, despite being incredibly sensitive ecosystems, have shown a surprising ability to recover from bleaching events – periods of stress caused by warming waters. While repeated and severe bleaching can lead to widespread coral death, some corals possess genes that make them more heat-tolerant, allowing them to survive and repopulate damaged reefs. This natural selection process offers a glimmer of hope, but it’s a race against time. The speed of climate change is outpacing the ability of many species to adapt naturally.

The study of about sea animals and their evolutionary history provides invaluable insights into their adaptive potential. By understanding the mechanisms that have allowed them to survive past challenges, we can better predict how they might respond to future threats and develop strategies to support their adaptation.

Current Threats and Their Impact

The challenges facing marine life today are multifaceted and interconnected. Climate change is arguably the most significant threat, driving ocean warming, acidification, and sea-level rise. Warmer waters lead to coral bleaching, disrupt marine food webs, and force species to migrate in search of suitable habitats. Ocean acidification, caused by the absorption of excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, hinders the ability of shellfish and corals to build their shells and skeletons.

Pollution, in its various forms, poses another serious threat. Plastic pollution, in particular, is devastating, with millions of tons of plastic entering the ocean each year. Sea animals ingest plastic debris, mistaking it for food, leading to starvation, entanglement, and death. Chemical pollutants, such as pesticides and heavy metals, accumulate in marine organisms, causing reproductive problems, immune suppression, and other health issues.

Overfishing has depleted many fish stocks, disrupting marine ecosystems and threatening the livelihoods of communities that depend on them. Destructive fishing practices, such as bottom trawling, damage seafloor habitats and indiscriminately kill non-target species.

Habitat destruction, driven by coastal development, dredging, and destructive fishing practices, further exacerbates these threats. Mangrove forests, seagrass beds, and coral reefs – vital nurseries and feeding grounds for countless marine species – are being lost at an alarming rate.

The Role of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

One of the most effective strategies for protecting marine life is the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). These designated areas restrict or prohibit certain activities, such as fishing, mining, and development, allowing marine ecosystems to recover and thrive. MPAs can take many forms, ranging from fully protected “no-take” zones to areas with limited restrictions.

The success of MPAs depends on several factors, including their size, location, and enforcement. Larger, well-managed MPAs tend to be more effective at protecting biodiversity and enhancing fish stocks. MPAs that are strategically located to encompass critical habitats, such as spawning grounds and migration routes, are particularly important. Effective enforcement is essential to ensure that regulations are followed and that MPAs are not exploited.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia is one of the largest and most well-known MPAs in the world. While facing significant challenges from climate change and coral bleaching, the park provides a vital refuge for a vast array of marine species. The Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii is another example of a successful MPA, protecting a remote and ecologically significant region of the Pacific Ocean.

Innovative Conservation Efforts: A Glimmer of Hope

Beyond MPAs, a range of innovative conservation efforts are underway to address the threats facing marine life. These include:

- Coral restoration: Scientists are actively working to restore damaged coral reefs by growing corals in nurseries and transplanting them onto degraded reefs.

- Plastic cleanup initiatives: Organizations are developing technologies to remove plastic debris from the ocean and prevent it from entering the marine environment.

- Sustainable fisheries management: Implementing quotas, gear restrictions, and other measures to ensure that fish stocks are harvested sustainably.

- Reducing pollution: Implementing stricter regulations on industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, and plastic production.

- Developing climate-resilient species: Identifying and breeding corals and other marine organisms that are more tolerant to warming waters and ocean acidification.

- Utilizing technology for monitoring: Employing drones, satellite imagery, and acoustic monitoring to track marine life populations and detect illegal activities.

The Importance of Community Involvement and Education

Conservation efforts are most effective when they involve local communities and promote education. Engaging local fishermen, coastal residents, and other stakeholders in the conservation process can foster a sense of ownership and ensure that conservation measures are sustainable.

Education plays a crucial role in raising awareness about the importance of marine life and the threats it faces. By educating the public about the interconnectedness of marine ecosystems and the impact of human activities, we can inspire people to take action to protect the ocean.

About sea animals and their incredible adaptations should be a core component of environmental education programs. Sharing stories of resilience and highlighting the beauty and wonder of the marine world can ignite a passion for conservation in future generations.

A Call to Action: Securing the Future of Marine Life

The future of marine life hangs in the balance. While the challenges are daunting, there is still hope. By embracing sustainable practices, supporting conservation efforts, and advocating for stronger environmental policies, we can help ensure that the ocean continues to thrive for generations to come.

We must recognize that the health of the ocean is inextricably linked to our own well-being. A healthy ocean provides us with food, oxygen, and climate regulation services. Protecting marine life is not just an environmental imperative; it’s a matter of self-preservation.

Let us all commit to becoming stewards of the ocean, working together to safeguard its incredible biodiversity and ensure a sustainable future for Sea Animals and for ourselves. The time to act is now.

WildWhiskers is a dedicated news platform for animal lovers around the world. From heartwarming stories about pets to the wild journeys of animals in nature, we bring you fun, thoughtful, and adorable content every day. With the slogan “Tiny Tails, Big Stories!”, WildWhiskers is more than just a news site — it’s a community for animal enthusiasts, a place to discover, learn, and share your love for the animal kingdom. Join WildWhiskers and open your heart to the small but magical lives of animals around us!